PRESENTATION: Memo. Remembering the Futures

In his book “In Search of Lost Time”, Marcel Proust reflects on the nature of memory, describing it as an embodied, sensory experience where a small trigger, like the taste of a made- leine, can suddenly evoke the past. Proust suggests that what is gone persists not only in our minds but also in the objects and sensations around us, highlighting how our iden- tities are closely tied to the environments we live in.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Fondation d’entreprise Martell Archive

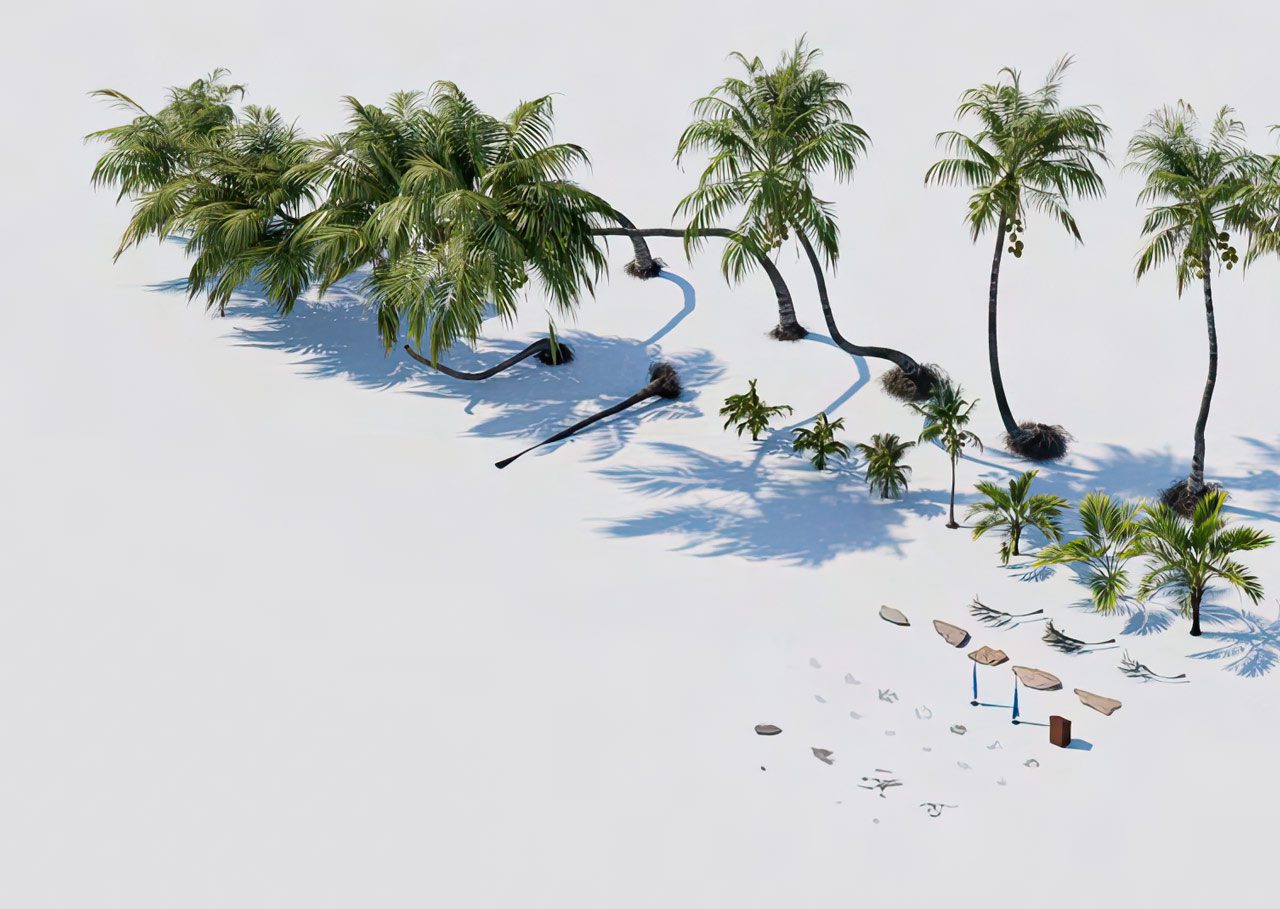

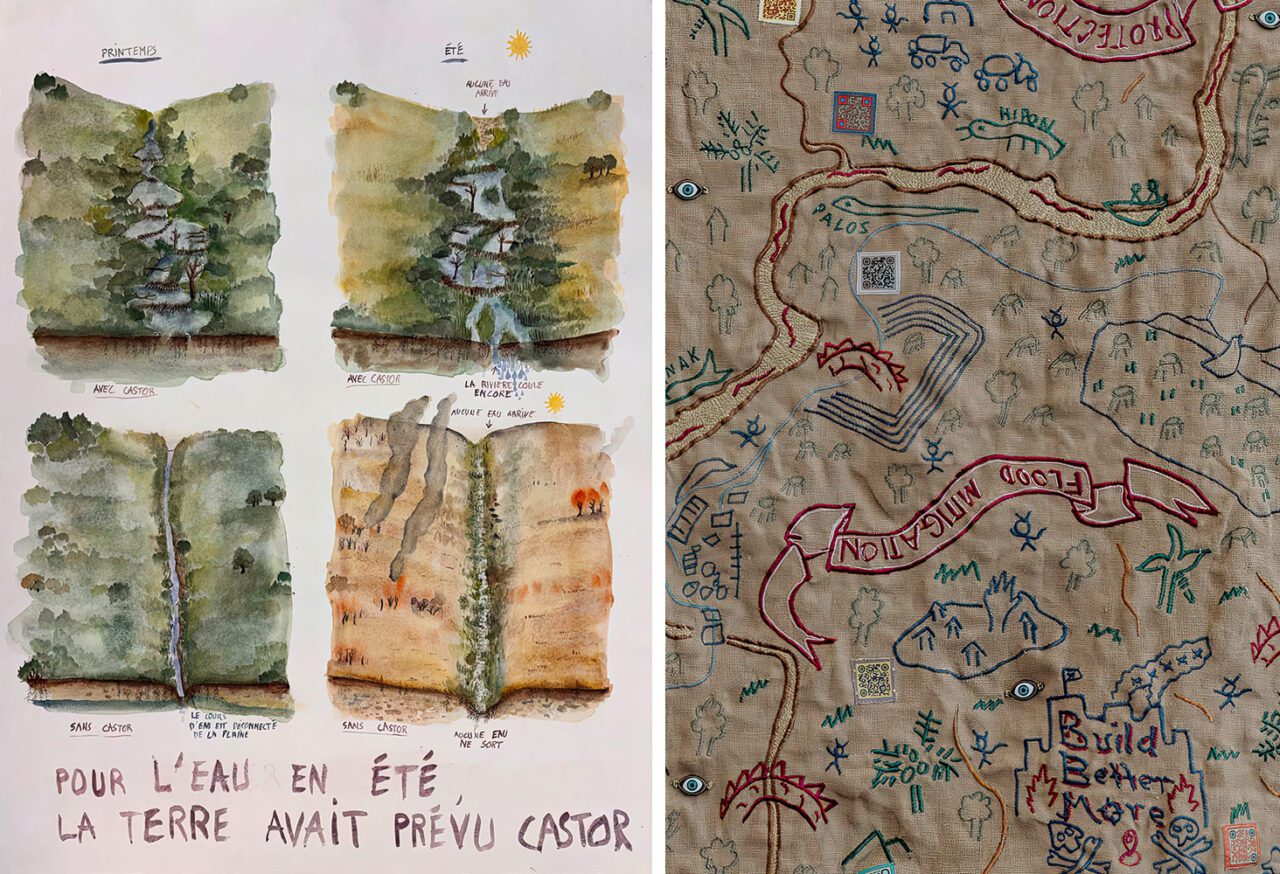

Through the lens of design, the exhibition “Memo. Remembering the Futures” explores the connections between memory, environment, and futures reflecting on pressing contemporary issues. In response to anthropogenic disturbances that degrade environments and multi-species relationships, the artists and designers featured in Memo develop new forms of memory and rituals that examine the future emotional and sensory impacts of our present and past actions. Informed by scientific and historical research, the sensitive narratives they create invite us to commit to ecosystem preservation. Their multisensory works—sometimes incorporating olfactory, auditory, or performative elements—act as memory triggers, urging us to remember and react., Representing all five continents, the 15 projects exhibited focus on exploring global issues through approaches that are embedded in specific geographical, ecological, and cultural contexts. The challenges they address (such as river management, monocultures, species extinction, and the preservation of ancestral knowledge) resonate particularly in Charente and more broadly in France. Promoting committed transdisciplinary approaches, these projects aim to nurture the ecological consciousness of visitors of all ages, provoke reflection, evoke emotion, motivate engagement, and encourage environmental action. Among the projects are: “Preserving a Vanishing Nation” by Collider & The Monkeys: Despite contributing minimally to global greenhouse gas emissions, Small Island Developing States (SIDS) such as Tuvalu—an archipelago situated in the heart of the Pacific Ocean—find themselves on the front lines of the climate crisis. At the COP26 conference in 2021, Simon Kofe, the Minister of Justice, Communication and Foreign Affairs of Tuvalu, delivered a poignant speech to the world. Standing in knee-deep water, Kofe warned the international community about the existential threats posed by rising sea levels to Tuvalu, which is expected to be submerged completely by the end of the 21st century, and whose population is already being forced into exile. A year later, at COP27, Kofe reiterated his mes- sage, announcing that Tuvalu would become the world’s “first digital nation,” preserving its “land, ocean and culture in the cloud” to safeguard them, regardless of what happens to the physical world. The process of digitalisation of Tuvalu is the result of a collaboration with two Australian creative agencies, The Monkeys and Collider. The project involves virtually reconstituting the archipelago’s features using 360˚ drone photography, 3D scanning, and digital mapping. Natural elements such as winds, ocean currents, environmental sounds, and vegetation are being reproduced and stored, alongside Tuvaluan (the local language), as well as the country’s traditions, legends, and oral culture. However, the migration of Tuvalu to the metaverse raises important questions and concerns about the effectiveness of technology as a solution to climate-induced disappearance and displacement. One such concern is the future sovereignty of the nation: currently, international law does not recognise states without a physical territory. “Recollecting a Bird’s Lost Voice” by Sally Ann McIntyre: The Huia (Heteralocha acutirostris) was a bird endemic to the North Island of New Zealand, considered sacred and kin by Māori. Following colonisation—and the process of cultural erasure that ensued—the bird was driven to extinction. Although the last confirmed sighting occurred in 1907, the species was not declared extinct until 1923. To this day, the date of the Huia’s extinction remains debated. Numerous expeditions to find living specimens continued un- til the 1960s, with some reported vocal encounters dismissed as inconclusive proof of the bird’s survival. While for Māori, the Huia’s presence still resonates “in the spirit world,” from a Western perspective, it vanished forever, leaving behind only silent traces: archived documents, museum artefacts, taxi- dermied specimens, transcripts of imitations of the bird’s vocalisation, and musical notations. Fascinated by the notion of sonic memories, artist Sally Ann McIntyre has explored the Huia’s history and legacy through sound for decades. Her work Collected Huia Notations (like shells on the shore when the sea of living memory has rece-ded) compiles four known Western musical notations of the bird’s song, including descriptions from 19th-century scientists, field notes, and Māori imitations. McIntyre emphasises “the paradox of a bird song only known through human vocalisation and notation,” questioning the fragility and perishability of material archives. In Collected Huia Notations, she engraved a piano notation of the bird’s song onto a wax cylinder, which degrades over time when played on a phonograph. The sound slowly vanishes, mirroring the Huia’s own disappearance.

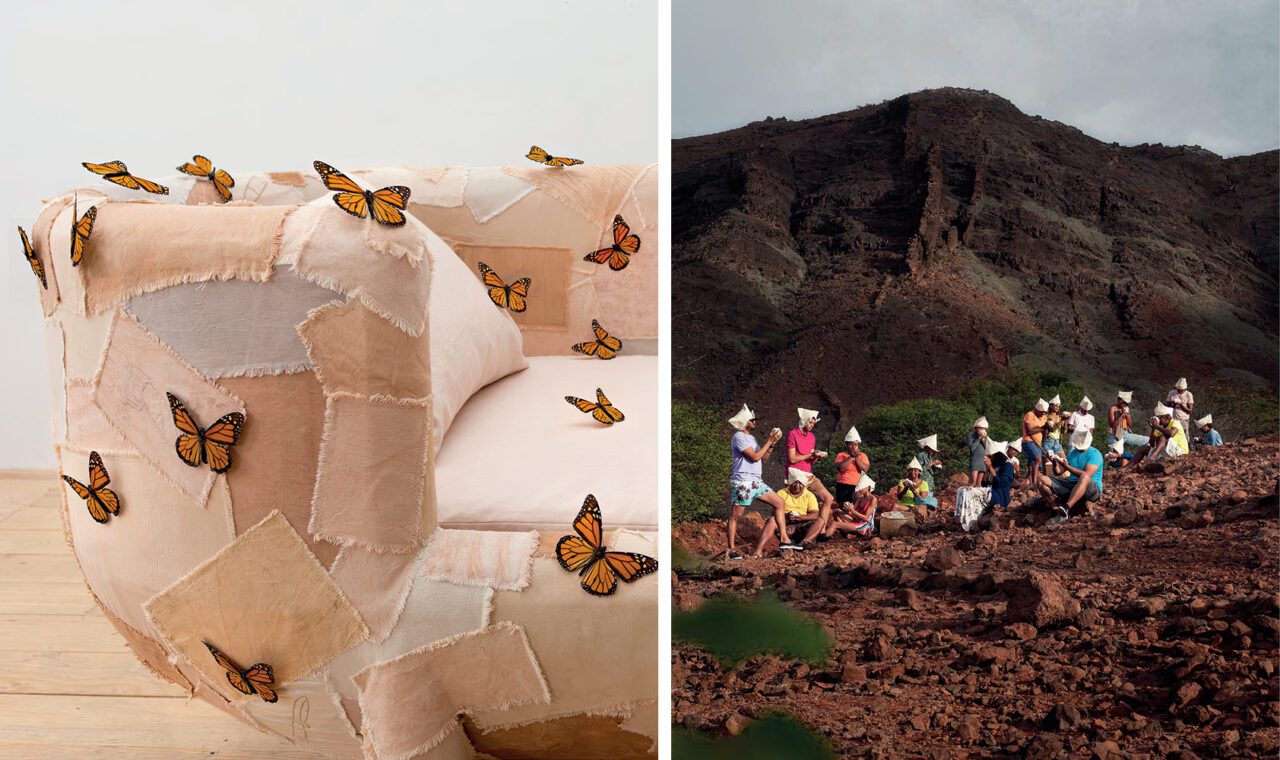

“Documenting the Dark Sides of Monoculture” by Fernando Laposse: In recent decades, global demand for avocados has surged, driven by changing dietary trends and their growing popularity in markets such as the United States. Thanks, in part, to trade agreements like NAFTA—an accord between Canada, Mexico, and the US effective since 1994 —Mexico’s avocado exports have exploded. Today, around 90% of the avocados imported into the US come from the Mexican state of Michoacán, where locals have embraced the green gold rush, clearing vast areas of forests to make space for monoculture plantations. The avocado trade has also attracted organised crime. Cartels extort farmers, engage in illegal logging, and forcibly push local communities into cultivating the fruit, harming those who resist. The controversies surrounding avocado cultivation, along with its environ- mental toll—particularly the destruction of vital habitats for species like the monarch butterfly—have remained hidden from the public eye until recently. In 2020, Fernando Laposse began exploring these complex issues with his long-term project Conflict Avocados. Through a documentary lens, Laposse seeks to uncover the multifaceted reality of avocado cultivation, shedding light on key events— such as community protests, ecological devastation, and the homicides of environmental leaders—that have marked the recent history of the Michoacán region. Mixing furniture pieces, material experimentation, textile story- telling, and first-hand photo and video documentation, Conflict Avocados employs design as a tool for eco-social awareness. The project is an homage to the human and other-than-human communities whose identities and cultures are being erased by rampant agricultural expansion driven by greed. “Embodying the Mountain” by Simone Kenyon & Lucy Cash: The Cairngorms, the highest and coldest mountain range in the British Isles, are located in the Scottish Highlands. This rugged landscape is home to free-flowing rivers and some of the rarest species in the UK. The Scottish poet Nan Shepherd (1893–1981) captured the essence of the range in The Living Mountain, a work first written in the 1940s but only published in 1977. This short book takes readers on a sensorial journey through the Cairngorms’ geology, geography, and climate, offering a deep exploration of the living beings that inhabit the region, and of the mountain itself. Through a personal and embodied account, Shepherd—a pioneer of women’s mountain walking—describes her intimate connection with the mountains and her effort to engage all her senses to fully experience and understand the lands- cape. She challenges her body to adopt new positions, shi ting perspectives from micro to macro in search of what she calls the “total mountain.” A response to Shepherd’s vivid portrayal of the Cairngorms, “How the Earth Must See Itself (A Thirling)” is a performance-film by Simone Kenyon and Lucy Cash. The piece offers a meditation on the landscape of the Cairngorms—specifically the Glen Feshie valley—and a celebration of Shepherd’s words. The all-women choreography explores and celebrates wo- men’s relationships with high and wild places. It also suggests that it is through our bodies—our touch and other sensory experiences—that we connect to a place, immerse ourselves in it, and become more aware. The reiteration of a single movement in time and space, the connection of our bare feet on soft moss—all

Participating Artists: Félix Blume, Emma Bruschi, Liselot Cobelens, Collider x The Monkeys, dach&zephir, Roberta Di Cosmo, Cian Dayrit & Cla Ruzol, Alexis Foiny, Suzanne Husky, Simone Kenyon & Lucy Cash, Fernando Laposse, Sally Ann McIntyre, Neve Insular, Bubu Ogisi / I A M I S I G O, Yesenia Thibault-Picazo

Photo: Liselot Cobelens, Dryland, 2022 © Liselot Cobelens, Jon Mensink, Ton Cobelens & Ad Wisse

Info: Curators: d-o-t-s (Laura Drouet / Olivier Lacrouts), Fondation d’entreprise Martell, 16 avenue Paul Firino Martell, Cognac, France, Duration: 13/6/2025-4/1/2026, Days & Hours: Wed-Sun 14:00-19:00, www.fondationdentreprisemartell.com/

Right : Roberta Di Cosmo, Rebirth-Trauma as a performative process, 2020, Photo © Giulia D’Addario

Right: Cian Dayrit, To Block the Flow of a River Is to Reject the Wisdom of the Earth, 2022. Photo © John McKenzie, Courtesy – Cian Dayrit & NOME Gallery

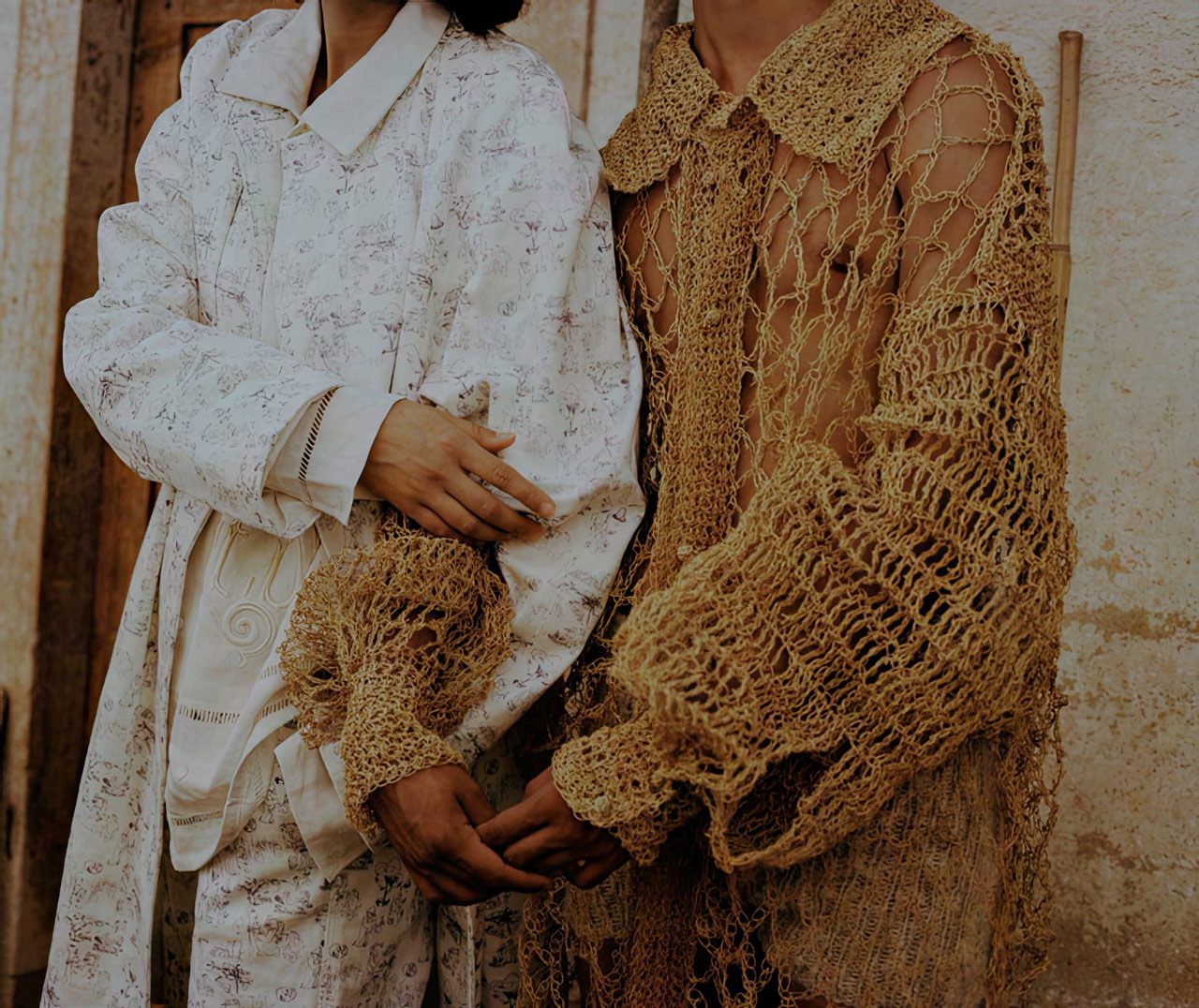

Right: Neve Insular, 100% Cotton, 2020. Neve Insular, Photo © Diogo Bento