ART CITIES: London-Hamad Butt

Hamad Butt was a British-Pakistani artist whose innovative work in the early 1990s bridged art and science, engaging deeply with themes of danger, transformation, and the AIDS crisis. His installations often incorporated hazardous materials, such as chlorine and iodine gases, to evoke the invisible threats of disease and societal fears. His work is characterized by its conceptual depth and technical complexity, often requiring collaboration with scientists and fabricators.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Whitechapel Gallery Archive

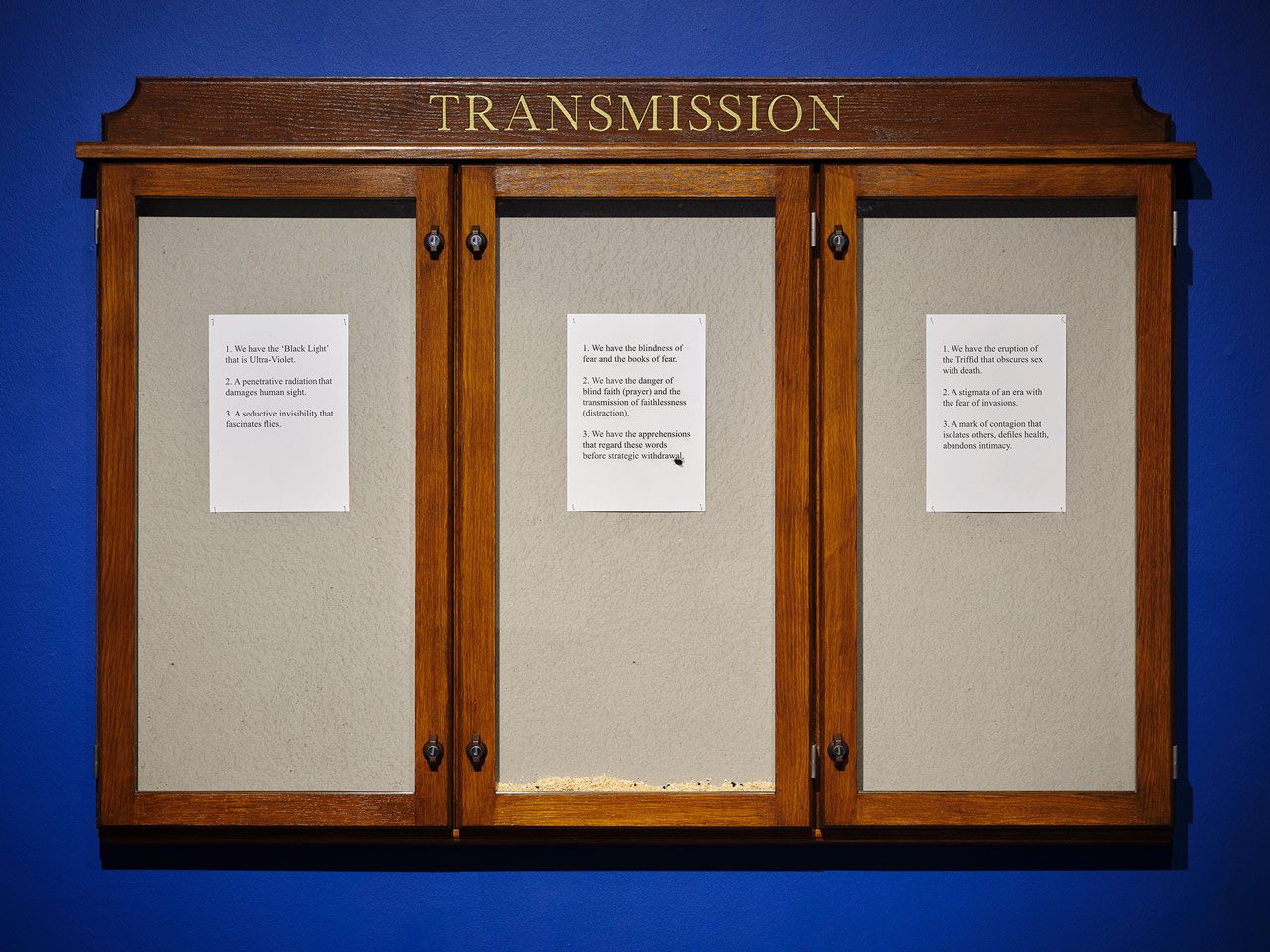

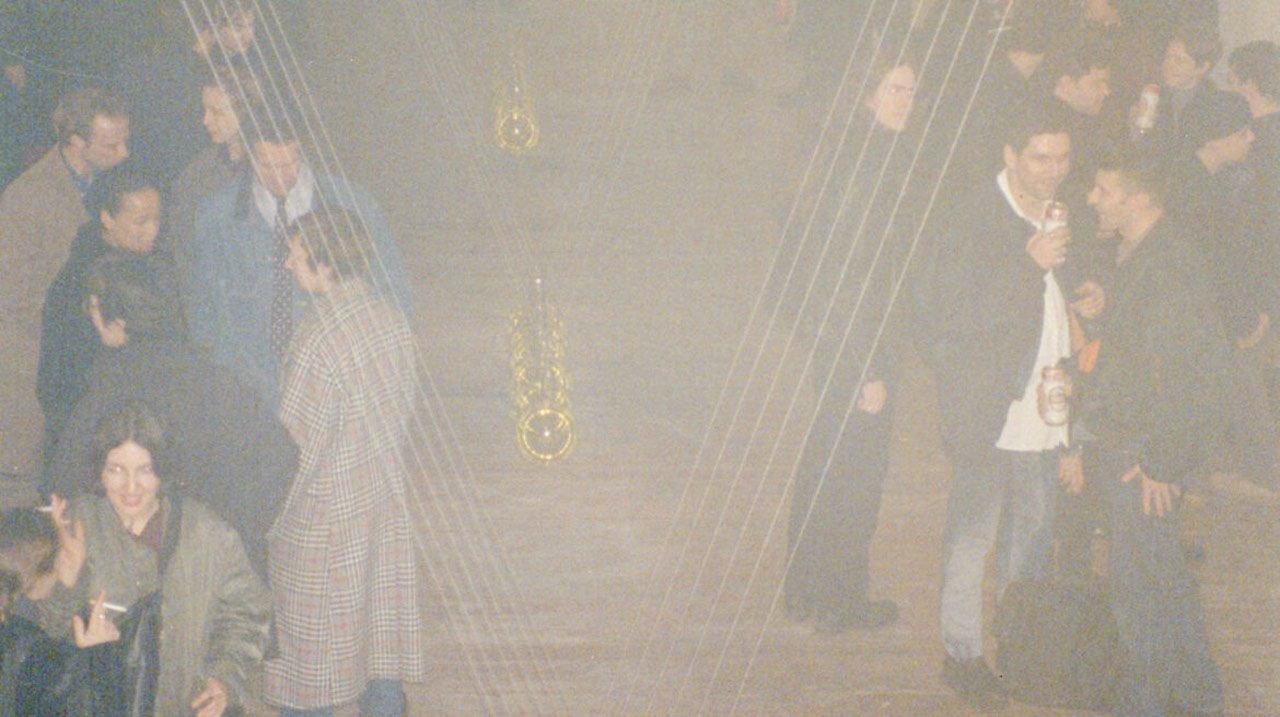

The exhibition “Apprehensions” brings together Hamad Butt’s iconic installations for the first time, alongside previously unseen paintings and drawings. Butt’s work often invokes the perceived threat of the racial, religious or national outsider. His references to the end of the world remind us of our own precarious state today – blighted by pandemics, looming environmental disaster and the ongoing migration crisis. Hamad Butt was born in Lahore, Pakistan in 1962. He lived in London from 1964 until his AIDS-related death in 1994, aged 32. Butt is distinctive for the beauty and danger of his sculptural installations, and for bringing art into conversation with scientific ideas and materials. He responded to living with AIDS though a conceptual approach: his works avoid directly representing stigma, sickness and death, and instead seek new and indirect ways of responding to the crisis. His works suggest alchemical processes of transformation and transubstantiation, and invoke the experience of being ‘frightened by one’s own capacity for attraction’, as he put it. British South Asian, queer, Muslim by upbringing, and HIV-positive, Butt understood his own body as unfixed in its identity and a prompt for fear in others. By making the viewer feel fearful or unsafe, Butt’s works ask vital questions about whose body is welcome in a particular space, community, or nation. “Transmission” was Butt’s first sculptural installation in 1990. It included glass books illuminated by ultraviolet light, a video, drawings, and an installation of live flies. This was his first active response to the AIDS crisis, prompted in part by his diagnosis as HIV-positive in 1987. The AIDS pandemic raged throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, fueled by government inaction and stigmatizing portrayals in the media. Butt was concerned with the ways sexual and racial minorities were scapegoated. This was a political commitment that emerged from his own embodied experience. “Transmission” is punctuated by images of the triffid, which Butt adopted from John Wyndham’s cold war sci-fi novel (and later film), “The Day of the Triffids” (1951). The triffid is a harbinger of blindness, contamination, and mass extinction, which Butt appropriated as an analogy for the HIV virus. “Fly-Piece” is a bio-art installation, one of the first ever made. Bluebottle flies metamorphose from maggots, feed on sugared paper printed with prophetic texts, and undergo cycles of life and death within an artificial habitat. This setup suggests the transmission of knowledge across generations of flies, reflecting themes of faith, decay, and disease. The fly represents invasive organisms that disrupt and pollute. In “Transmission”, the splayed books and circular layout draw from the presentation of the Quran at a khathēm, an Islamic funerary rite where scripture is read collectively. Ultraviolet light can be harmful to human eyes. The images etched on glass are difficult or dangerous to see. There is an unresolvable contradiction here between the ‘transmission’ of information and our human capacity to safely receive it. “Transmission” concerns the dangers of ‘blind faith’ as it relates to religion and the purported objectivity of scientific knowledge. Butt made “Triffids” using rudimentary analogue video-editing software. It was conceived as part of “Transmission”. A triffid undergoes serial transformations as the hand-drawn figure and backgrounds are processed to cycle through a vivid color palette. Meeting a violent end, the triffid is burned, shot, and killed. Butt drew the triffid to recall a scrotum and ejaculating penis. Its resemblance to juvenile graffiti brings a sexual connotation to the central theme of transmission, for example of body fluids or of death. Completed in 1992, “Familiars” comprises three sculptures that incorporate bromine, iodine and chlorine: three halogens in their primary states of matter.

“Familiars” emphasizes the conflicted attraction to and repulsion by that which makes us fearful. It spikes the intensity of Butt’s previous explorations of dangerous or unpleasant materials. “Familiars 1: Substance Sublimation Unit” is a steel ladder made of glass rungs, each filled with an electrical element and crystals of solid iodine. The current ascends the ladder, intermittently heating the rungs, causing the iodine to sublimate into a purple vapor. In “Familiars 2: Hypostasis”, three tall, curved metal poles, reminiscent of Islamic arches, contain bromine-filled tubes at the tips. In “Familiars 3: Cradle”, named after Newton’s cradle, 18 vacuum-sealed glass spheres are filled with lethal yellow-green chlorine gas. If smashed together, the gas – a respiratory irritant – would be released into the air. In “Hypostasis”, liquid bromine is held aloft in glass tubes. Its shape invokes an arch, inspired perhaps by Islamic architectures he admired in Pakistan and Southern Spain. Bromine is essential for human life and used in the manufacture of disinfectants, sedatives and petrol. Bromine is also toxic, can burn the skin, and is carcinogenic. ‘Hypostasis’ refers to an underlying reality or essence in philosophy, theology, or medicine. In theology, it denotes each element of the Holy Trinity sharing one divine substance. Butt was a prolific maker of paintings, drawings and etchings. He acquired advanced skills, including in printmaking, by attending two undergraduate degrees and numerous short courses throughout the 1980s. He showed some of these works in galleries from 1981 until 1987. He developed a signature style informed by his fascination with modernist ‘masters’ including Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, André Masson and Jean Cocteau. Repeating images and scenes include cramped homes or clubs lit by bare lightbulbs, contorted male nudes in sexually suggestive poses, mythological references, and situations of barely subdued violence. His lifelong exploration of fear, danger and desire begins with these earliest works, setting the scene for the more formally ambitious approaches to the same ideas in his sculptural installations. From his earliest drawings from life, Butt developed a dynamic, forceful line. His spontaneous and intuitive charcoal drawings suggest a transformation in his approach in the move away from faithful depiction and narration towards a distillation – perhaps an alchemical transformation – of line and image. Armed with dynamic ways of working, Butt continued to make works on paper, developing a fresh style and new conceptual vocabulary. These works using pastel and pencil were made during the development of “Familiars” and include references to “iwans” (Islamic arches) and “mihrabs” (mosque niches), and alchemical, scientific and mathematical symbology. They were discovered posthumously in a portfolio. Titles and dates were not recorded. Three archival vitrines present materials relating to Butt’s development as an artist, including statements, sketches, schematic drawings, reference materials and documentation. In March 1994, six months before his death, and critically ill, Butt consented to an interview by his brother Jamal at their parents’ home in Ilford. It is one of only two extant interviews with the artist. Candid and uncompromising, Butt explains his most pressing motivations. He reflects on his achievements, from his early paintings to his sculptural installations, and describes his ambitions for the future. Domestic life intrudes upon the conversation throughout. Butt’s life and career were cruelly curtailed. Archival materials indicate some of his plans that could not come to pass, and document the artist’s efforts to live with AIDS, treat his illnesses, and reckon with the prospect of dying too soon.

Photo: Hamad Butt, Transmission, 1990, Glass, steel, ultraviolet lights and electrical cables Dimensions variable., Installation at Milch, London, 1990. Tate. Image © Jamal Butt. Photo: Tim Martin

Info: Curators: Dominic Johnson, Seán Kissane and Gilane Tawadros, Whitechapel Gallery, 77-82 Whitechapel High St, London, United Kingdom, Duration: 4/6-7/9/2025, Days & Hours: Tue-Wed & Fri-Sat 10:00-16:30, Thu 10:00-20:00, Sun 11:00-16:30, www.whitechapelgallery.org/