ARCHITECTURE: Peter Eisenman

Whether built, written or drawn, the work of renowned architect, theorist and educator Peter Eisenman (11/8/1932- ) known for his radical designs and architectural theories is characterized by Deconstructivism, with an interest in signs, symbols and the processes of making meaning always at the foreground. As such, Eisenman has been one of architecture’s foremost theorists of recent decades; however he has also at times been a controversial figure in the architectural world, professing a disinterest in many of the more pragmatic concerns that other architects engage in.

Whether built, written or drawn, the work of renowned architect, theorist and educator Peter Eisenman (11/8/1932- ) known for his radical designs and architectural theories is characterized by Deconstructivism, with an interest in signs, symbols and the processes of making meaning always at the foreground. As such, Eisenman has been one of architecture’s foremost theorists of recent decades; however he has also at times been a controversial figure in the architectural world, professing a disinterest in many of the more pragmatic concerns that other architects engage in.

By Efi Michalarou

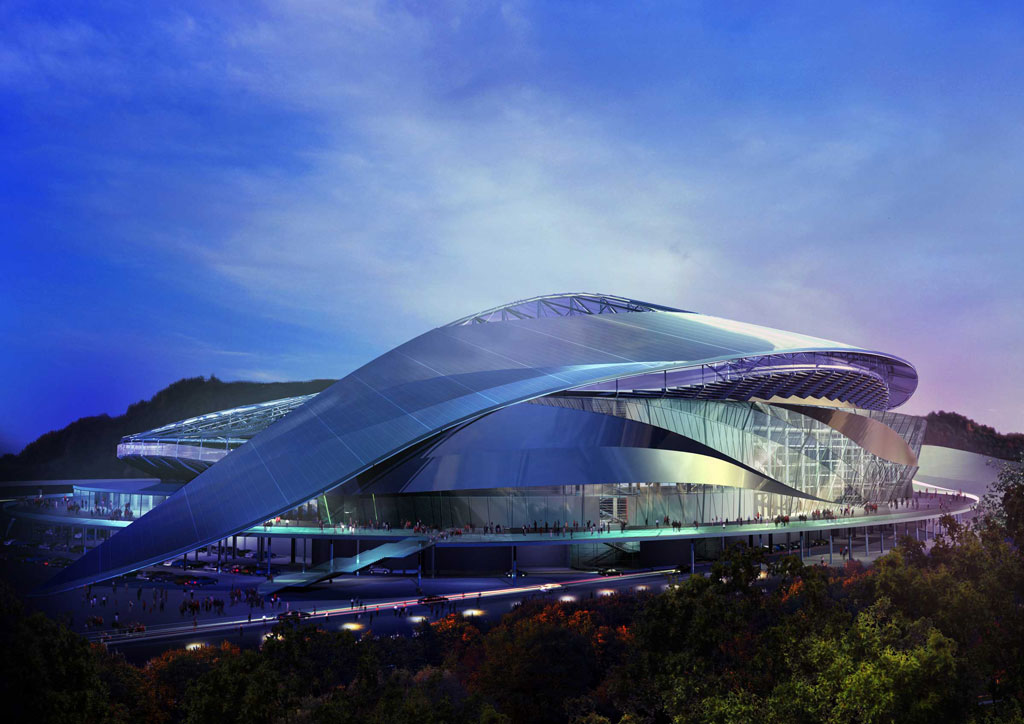

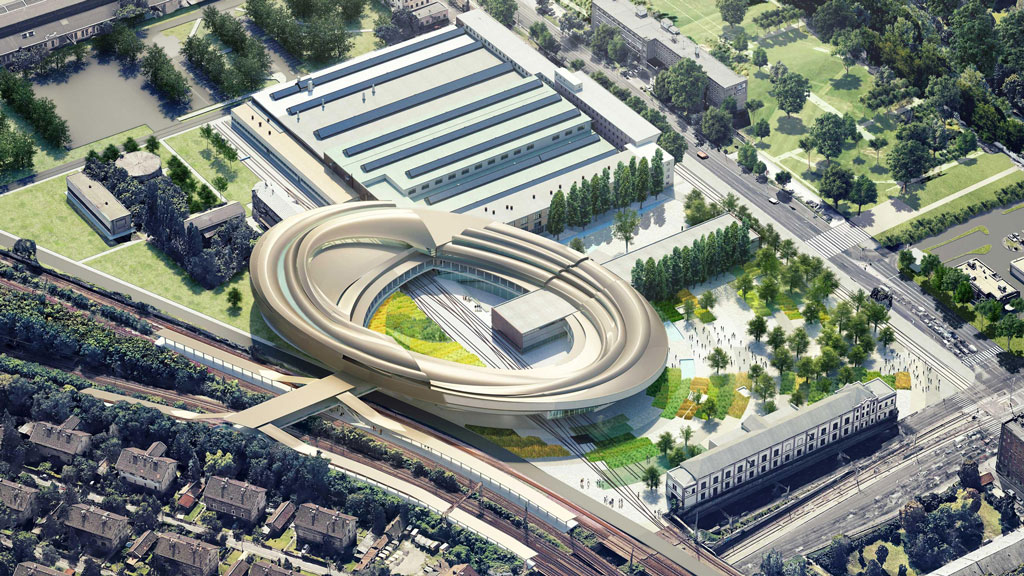

Peter Eisenman was born to Jewish parents in Newark, New Jersey. As a child, he attended Columbia High School located in Maplewood, New Jersey. He transferred in to the architecture school as an undergraduate at Cornell University and gave up his position on the swimming team in order to commit full-time to his studies. He received a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Cornell, a Master of Architecture degree from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, and M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from the University of Cambridge. He received an honorary degree from Syracuse University School of Architecture in 2007. In 1967 he founded the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in New York City, and from 1973 to 1982 he was editor of the institute’s publication, “Oppositions” which was one of the foremost journals of architectural thought. He also taught at a variety of universities, including the University of Cambridge, Princeton University, Yale University, Harvard University, the Ohio State University, and Cooper Union in New York City. During his tenure at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, Eisenman became renowned as a theoretician of architecture. He thought outside the traditional parameters of “built work” concerning himself instead with a conceptual form of architecture, in which the process of architecture is represented through diagrams rather than through actual construction. In his designs he fragmented existing architectural models in a way that drew upon concepts from philosophy and linguistics, specifically the ideas of the philosophers Friedrich Nietzsche and Jacques Derrida and the linguist Noam Chomsky. Because of these affiliations, Eisenman was alternately classified as a postmodernist, deconstructivist, and poststructuralist. Beginning in the late 1960s, Eisenman’s ideas took form in a series of numbered houses—e.g., House I (1967–68) in Princeton, New Jersey, House II (1969–70) in Hardwick, Vermont, and House VI (1972–75) in Cornwall, Connecticut. These structures were in effect a series of experiments that referred to Modernism’s rigid geometry and rectangular plans but took these elements to a theoretical extreme: in details such as stairways that led nowhere and columns that did not function as support for the structure, Eisenman rejected the functional concept that was at the core of much Modernism. Eisenman was the main exponent of the group known as the New York Five (or Five Architects) – taken from the name of their collective exhibition at MoMA (1967) and the book “Five Architects” (1972) – alongside John Hejduk, Michael Graves, Charles Gwathmey and Richard Meier. The group was inspired by Le Corbusier’s work and Modernism in general. In 1980 Eisenman established a professional practice in New York City. He embarked on a number of major projects, characterized by disconcerting forms, angles, and materials, including the Wexner Center for the Arts (1983–89) at the Ohio State University in Columbus, the Greater Columbus (Ohio) Convention Center (1993), and the Aronoff Center for Design and Art (1996) at the University of Cincinnati (Ohio). In the Wexner Center, one of the best known of his commissions, Eisenman flouted traditional planning by creating a north-south grid for the spine of the building that was exactly perpendicular to the east-west axis of the university campus. He also challenged viewers’ expectation of materials, enclosing half the space in glass and the other half in scaffolding. Among his later projects were the award-winning Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (opened 2005) in Berlin and the University of Phoenix Stadium (opened 2006) in Glendale, Arizona.

Peter Eisenman was born to Jewish parents in Newark, New Jersey. As a child, he attended Columbia High School located in Maplewood, New Jersey. He transferred in to the architecture school as an undergraduate at Cornell University and gave up his position on the swimming team in order to commit full-time to his studies. He received a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Cornell, a Master of Architecture degree from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, and M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from the University of Cambridge. He received an honorary degree from Syracuse University School of Architecture in 2007. In 1967 he founded the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in New York City, and from 1973 to 1982 he was editor of the institute’s publication, “Oppositions” which was one of the foremost journals of architectural thought. He also taught at a variety of universities, including the University of Cambridge, Princeton University, Yale University, Harvard University, the Ohio State University, and Cooper Union in New York City. During his tenure at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, Eisenman became renowned as a theoretician of architecture. He thought outside the traditional parameters of “built work” concerning himself instead with a conceptual form of architecture, in which the process of architecture is represented through diagrams rather than through actual construction. In his designs he fragmented existing architectural models in a way that drew upon concepts from philosophy and linguistics, specifically the ideas of the philosophers Friedrich Nietzsche and Jacques Derrida and the linguist Noam Chomsky. Because of these affiliations, Eisenman was alternately classified as a postmodernist, deconstructivist, and poststructuralist. Beginning in the late 1960s, Eisenman’s ideas took form in a series of numbered houses—e.g., House I (1967–68) in Princeton, New Jersey, House II (1969–70) in Hardwick, Vermont, and House VI (1972–75) in Cornwall, Connecticut. These structures were in effect a series of experiments that referred to Modernism’s rigid geometry and rectangular plans but took these elements to a theoretical extreme: in details such as stairways that led nowhere and columns that did not function as support for the structure, Eisenman rejected the functional concept that was at the core of much Modernism. Eisenman was the main exponent of the group known as the New York Five (or Five Architects) – taken from the name of their collective exhibition at MoMA (1967) and the book “Five Architects” (1972) – alongside John Hejduk, Michael Graves, Charles Gwathmey and Richard Meier. The group was inspired by Le Corbusier’s work and Modernism in general. In 1980 Eisenman established a professional practice in New York City. He embarked on a number of major projects, characterized by disconcerting forms, angles, and materials, including the Wexner Center for the Arts (1983–89) at the Ohio State University in Columbus, the Greater Columbus (Ohio) Convention Center (1993), and the Aronoff Center for Design and Art (1996) at the University of Cincinnati (Ohio). In the Wexner Center, one of the best known of his commissions, Eisenman flouted traditional planning by creating a north-south grid for the spine of the building that was exactly perpendicular to the east-west axis of the university campus. He also challenged viewers’ expectation of materials, enclosing half the space in glass and the other half in scaffolding. Among his later projects were the award-winning Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (opened 2005) in Berlin and the University of Phoenix Stadium (opened 2006) in Glendale, Arizona.