ART-TRIBUTE:Ellsworth Kelly

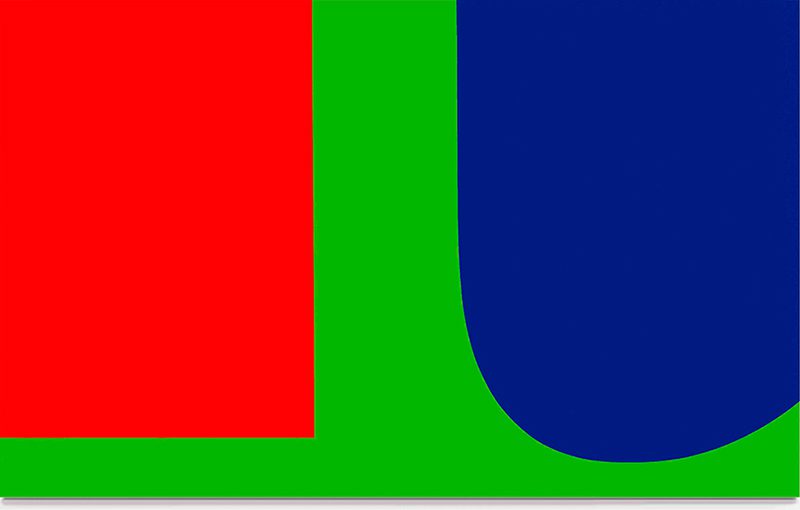

Ellsworth Kelly, one of America’s great 20th Century Abstract artists, who in the years after WWII shaped a distinctive style of American painting by combining the solid shapes and brilliant colors of European Abstraction with forms distilled from everyday life. Maintaining a persistent focus on the dynamic relationships between shape, form and color, Kelly was one of the first artists to create irregularly shaped canvases. He died in 27/12/15 at his home in Spencertown, N.York.

Ellsworth Kelly, one of America’s great 20th Century Abstract artists, who in the years after WWII shaped a distinctive style of American painting by combining the solid shapes and brilliant colors of European Abstraction with forms distilled from everyday life. Maintaining a persistent focus on the dynamic relationships between shape, form and color, Kelly was one of the first artists to create irregularly shaped canvases. He died in 27/12/15 at his home in Spencertown, N.York.

By Dimitris Lempesis

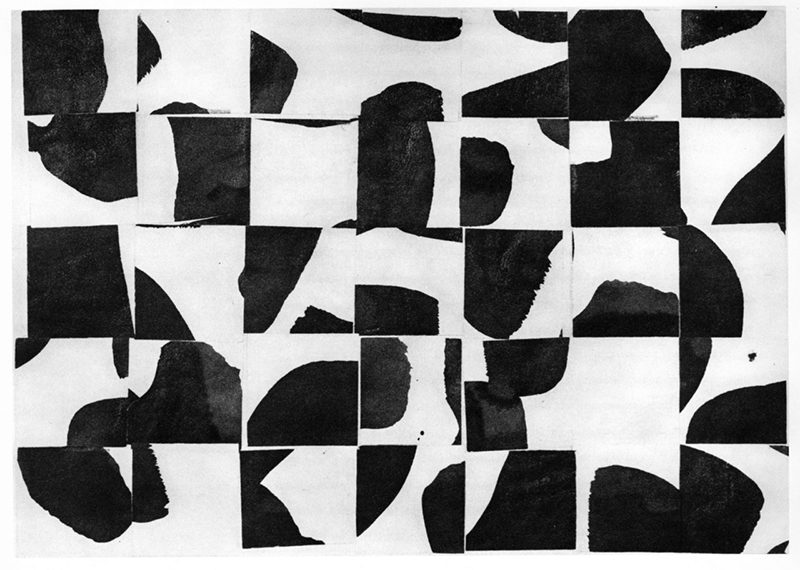

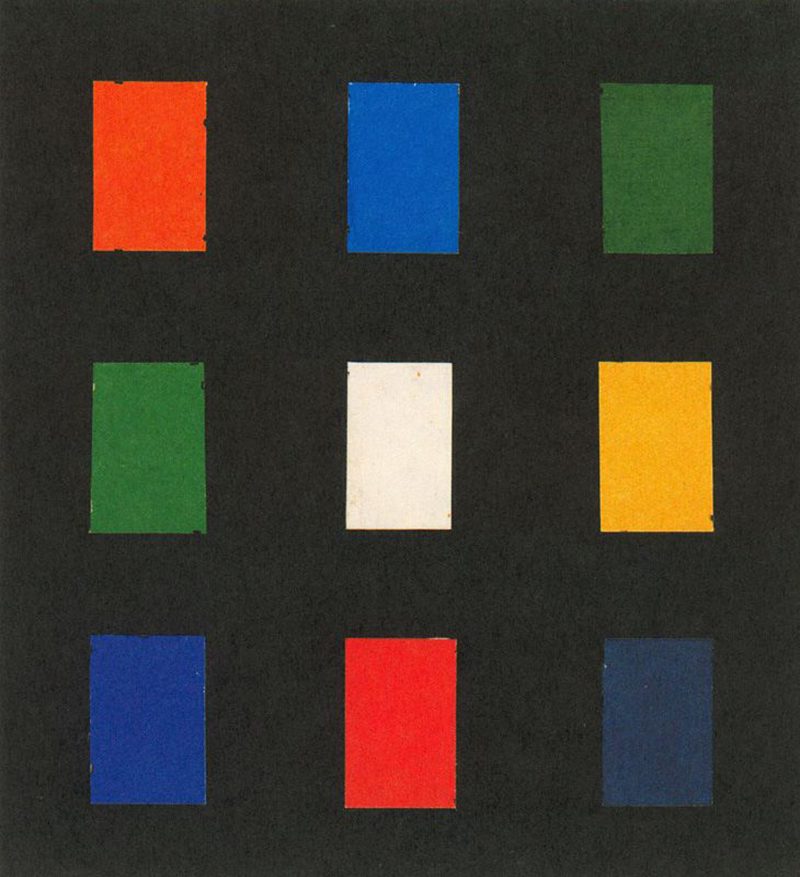

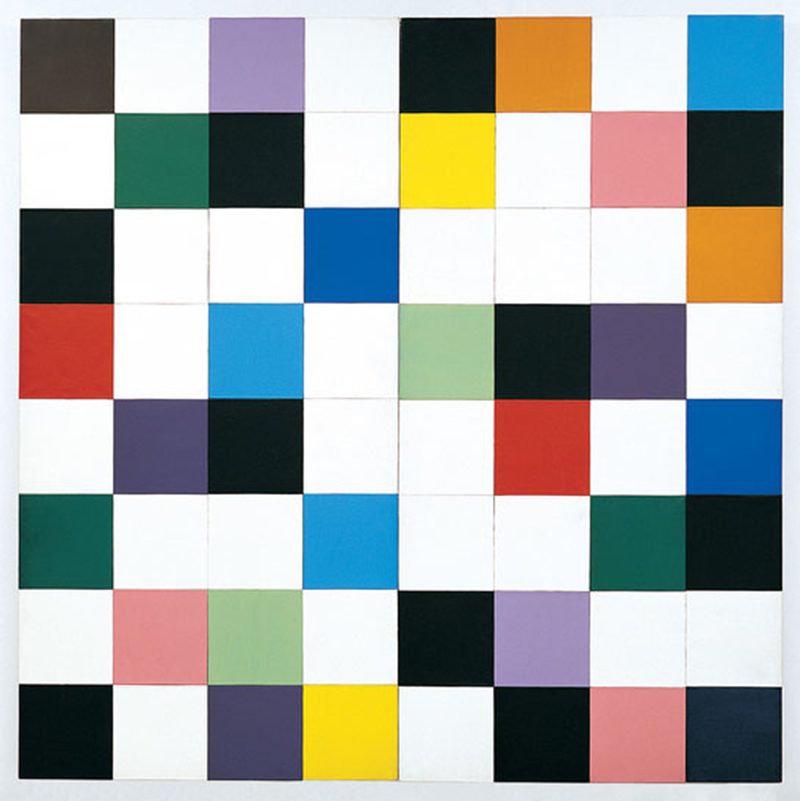

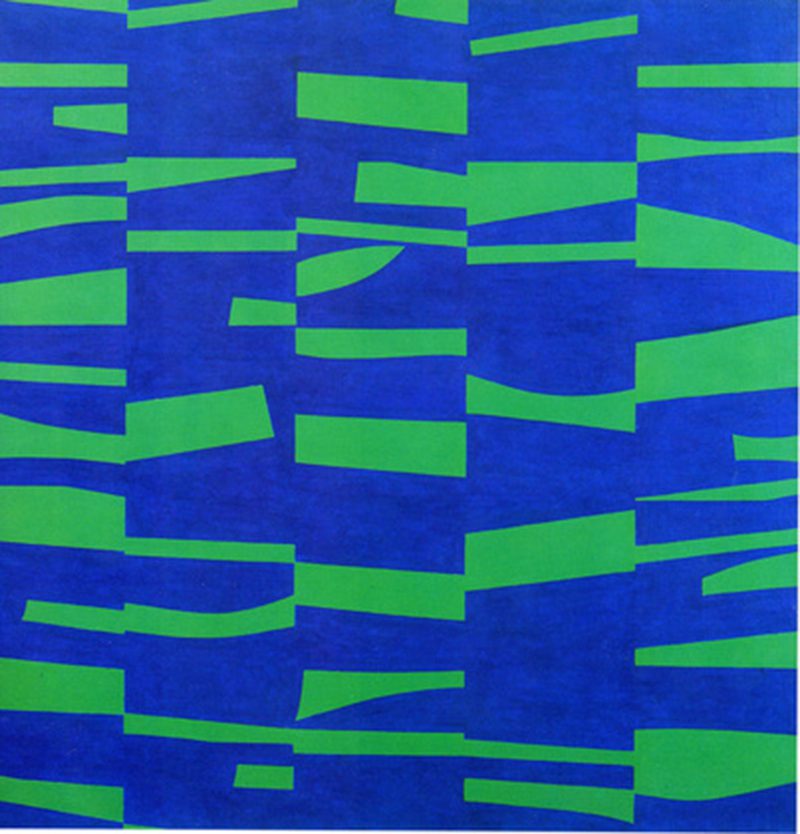

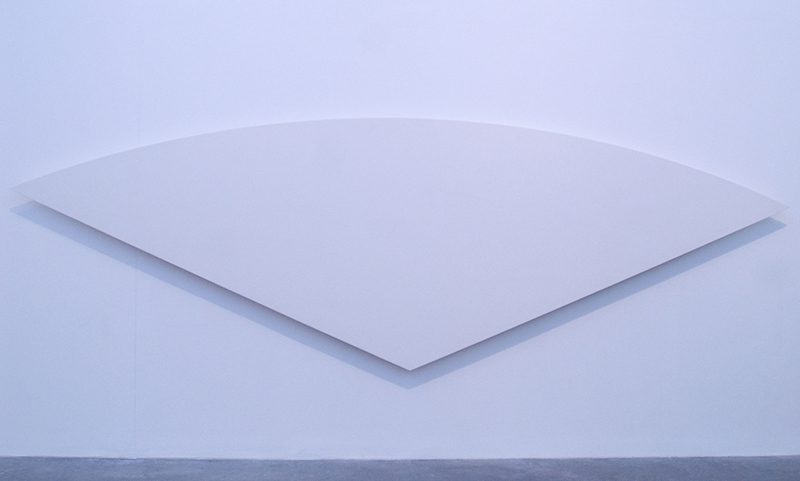

Born in Newburgh, New York in 31/5/23, Ellsworth Kelly grew up in northern New Jersey, where he spent much of his time alone, often watching birds and insects. These observations of nature would later inform his unique way of creating and looking at art. After graduating from high school, he studied technical art and design at the Pratt Institute from 1941-42. In 1943, Kelly enlisted in the army and joined the camouflage unit 23rd Headquarters Special Troops called “the Ghost Army”, which had among its members many artists and designers. The unit’s task was to misdirect enemy soldiers with inflatable tanks. While in the army, Kelly served in France, England and Germany, including a brief stay in Paris. His visual experiences with camouflage and shadows, as well as his short time in Paris strongly impacted Kelly’s aesthetic and future career path. After his army discharge in 1945, Kelly studied at the Boston Museum of the Fine Arts School for two years, where his work was largely figurative and classical. In 1948, with support from the G.I. Bill (The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (P.L. 78-346, 58 Stat. 284m), known informally as the G.I. Bill, was a law that provided a range of benefits for returning WW II veterans), he returned to Paris. Abstract Expressionism was taking shape in the U.S., but Kelly’s physical distance allowed him to develop his style away from its dominating influence. He enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, saying at that point, “I didn’t go to Paris to go to school; I just wanted to look around, and see a few paintings. The Beaux-Arts was the only place that didn’t care about attendance. I painted the nude that got me in, and then the tutor never saw me again” and “I wasn’t interested in abstraction at all. I was interested in Picasso, in the Renaissance”. Romanesque and Byzantine art appealed to him, as did the Surrealist method of automatic drawing and the concept of art dictated by chance. While absorbing the work of these movements and artists, Kelly has said, “I was deciding what I didn’t want in a painting, and just kept throwing things out – like marks, lines and the painted edge”. During a visit to the Musee d’Art Moderne in Paris, he paid more attention to the museum’s windows than to the art on display. Directly inspired by this observation, he created his own version of these windows. After that point, he has said, “Painting as I had known it was finished for me. Everywhere I looked, everything I saw, became something to be made, and it had to be made exactly as it was, with nothing added”. This view shaped what would become Kelly’s overarching artistic perspective throughout his career, and his way of transforming what he saw in reality into the abstracted content, form, and colors of his art. After being well received within the Paris art world, Kelly left for New York in 1954. While his work markedly differed from that of his New York colleagues, he said, “By the time I got to New York I felt like I was already through with gesture. I wanted something more subdued, less conscious.. I didn’t want my personality in it. The space I was interested in was not the surface of the painting, but the space between you and the painting”. Although his work was not a reaction to Abstract Expressionism, Kelly did find inspiration in the large scale of the Abstract Expressionist works and continued creating ever-larger paintings and sculptures. In New York City, while creating canvases with precise blocks of solid color, he lived in a community with such artists as James Rosenquist, Jack Youngerman, and Agnes Martin. The Betty Parsons Gallery gave Kelly his first solo show in 1956. In 1959, he was part of the Museum of Modern Art’s major “Sixteen Americans” exhibition, alongside Jasper Johns, Frank Stella and Robert Rauschenberg. His rectangular panels gave way to unconventionally shaped canvases, painted in bold, monochromatic colors. At the same time, Kelly was making sculptures comprised of flat shapes and bright color. His sculptures were largely two-dimensional and shallow, more so than his paintings. Conversely, in the paintings he was experimenting with relief. During the 1960s, Kelly began printmaking as well. Throughout his career, frequent subjects for his lithographs and drawings have been simple, lined renditions of plants, leaves and flowers. In these works, as with his abstracted paintings, Kelly placed primary importance in form and shape. In 1970, Kelly moved to upstate New York. Over the next two decades, he made use of his bigger studio space by creating even larger multi-panel works and outdoor steel, aluminum and bronze sculptures. He also adopted more curved forms in both canvas shapes and areas of precisely painted color. In addition to creating totemic sculptures, Kelly began making publicly commissioned artwork, including a sculpture for the city of Barcelona in 1978 and an installation for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. in 1993. Matthew Marks of the Matthew Marks Gallery said Kelly died of natural causes at his home in Spencertown. Marks said he was told of the death by Kelly’s partner, Jack Shear.

Born in Newburgh, New York in 31/5/23, Ellsworth Kelly grew up in northern New Jersey, where he spent much of his time alone, often watching birds and insects. These observations of nature would later inform his unique way of creating and looking at art. After graduating from high school, he studied technical art and design at the Pratt Institute from 1941-42. In 1943, Kelly enlisted in the army and joined the camouflage unit 23rd Headquarters Special Troops called “the Ghost Army”, which had among its members many artists and designers. The unit’s task was to misdirect enemy soldiers with inflatable tanks. While in the army, Kelly served in France, England and Germany, including a brief stay in Paris. His visual experiences with camouflage and shadows, as well as his short time in Paris strongly impacted Kelly’s aesthetic and future career path. After his army discharge in 1945, Kelly studied at the Boston Museum of the Fine Arts School for two years, where his work was largely figurative and classical. In 1948, with support from the G.I. Bill (The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (P.L. 78-346, 58 Stat. 284m), known informally as the G.I. Bill, was a law that provided a range of benefits for returning WW II veterans), he returned to Paris. Abstract Expressionism was taking shape in the U.S., but Kelly’s physical distance allowed him to develop his style away from its dominating influence. He enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, saying at that point, “I didn’t go to Paris to go to school; I just wanted to look around, and see a few paintings. The Beaux-Arts was the only place that didn’t care about attendance. I painted the nude that got me in, and then the tutor never saw me again” and “I wasn’t interested in abstraction at all. I was interested in Picasso, in the Renaissance”. Romanesque and Byzantine art appealed to him, as did the Surrealist method of automatic drawing and the concept of art dictated by chance. While absorbing the work of these movements and artists, Kelly has said, “I was deciding what I didn’t want in a painting, and just kept throwing things out – like marks, lines and the painted edge”. During a visit to the Musee d’Art Moderne in Paris, he paid more attention to the museum’s windows than to the art on display. Directly inspired by this observation, he created his own version of these windows. After that point, he has said, “Painting as I had known it was finished for me. Everywhere I looked, everything I saw, became something to be made, and it had to be made exactly as it was, with nothing added”. This view shaped what would become Kelly’s overarching artistic perspective throughout his career, and his way of transforming what he saw in reality into the abstracted content, form, and colors of his art. After being well received within the Paris art world, Kelly left for New York in 1954. While his work markedly differed from that of his New York colleagues, he said, “By the time I got to New York I felt like I was already through with gesture. I wanted something more subdued, less conscious.. I didn’t want my personality in it. The space I was interested in was not the surface of the painting, but the space between you and the painting”. Although his work was not a reaction to Abstract Expressionism, Kelly did find inspiration in the large scale of the Abstract Expressionist works and continued creating ever-larger paintings and sculptures. In New York City, while creating canvases with precise blocks of solid color, he lived in a community with such artists as James Rosenquist, Jack Youngerman, and Agnes Martin. The Betty Parsons Gallery gave Kelly his first solo show in 1956. In 1959, he was part of the Museum of Modern Art’s major “Sixteen Americans” exhibition, alongside Jasper Johns, Frank Stella and Robert Rauschenberg. His rectangular panels gave way to unconventionally shaped canvases, painted in bold, monochromatic colors. At the same time, Kelly was making sculptures comprised of flat shapes and bright color. His sculptures were largely two-dimensional and shallow, more so than his paintings. Conversely, in the paintings he was experimenting with relief. During the 1960s, Kelly began printmaking as well. Throughout his career, frequent subjects for his lithographs and drawings have been simple, lined renditions of plants, leaves and flowers. In these works, as with his abstracted paintings, Kelly placed primary importance in form and shape. In 1970, Kelly moved to upstate New York. Over the next two decades, he made use of his bigger studio space by creating even larger multi-panel works and outdoor steel, aluminum and bronze sculptures. He also adopted more curved forms in both canvas shapes and areas of precisely painted color. In addition to creating totemic sculptures, Kelly began making publicly commissioned artwork, including a sculpture for the city of Barcelona in 1978 and an installation for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. in 1993. Matthew Marks of the Matthew Marks Gallery said Kelly died of natural causes at his home in Spencertown. Marks said he was told of the death by Kelly’s partner, Jack Shear.