TRACES:Alighiero Boetti

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the Italian Conceptual artist Alighiero e Boetti (16/12/1940-24/2/1994). Who used his work as political manifesto. Unlike other Arte Povera artists, he traveled to Afghanistan to discover order and disorder. His work has proven a difficult fit within institutional discussions of art since the 1960s. Frequent association with the Arte Povera group has seemed equally problematic insomuch as the term accounts only for the earliest elements of the artist’s widely varied production. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the Italian Conceptual artist Alighiero e Boetti (16/12/1940-24/2/1994). Who used his work as political manifesto. Unlike other Arte Povera artists, he traveled to Afghanistan to discover order and disorder. His work has proven a difficult fit within institutional discussions of art since the 1960s. Frequent association with the Arte Povera group has seemed equally problematic insomuch as the term accounts only for the earliest elements of the artist’s widely varied production. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

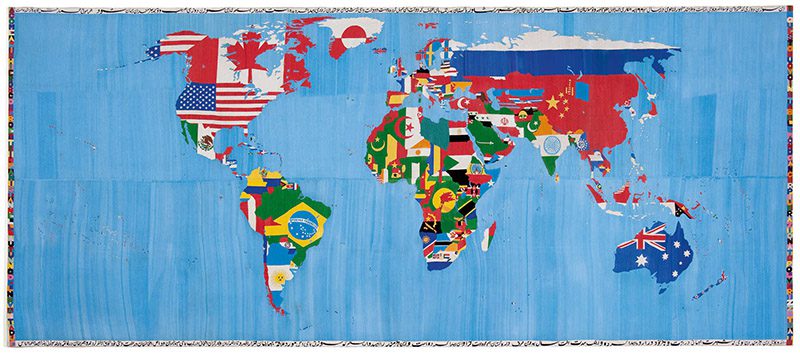

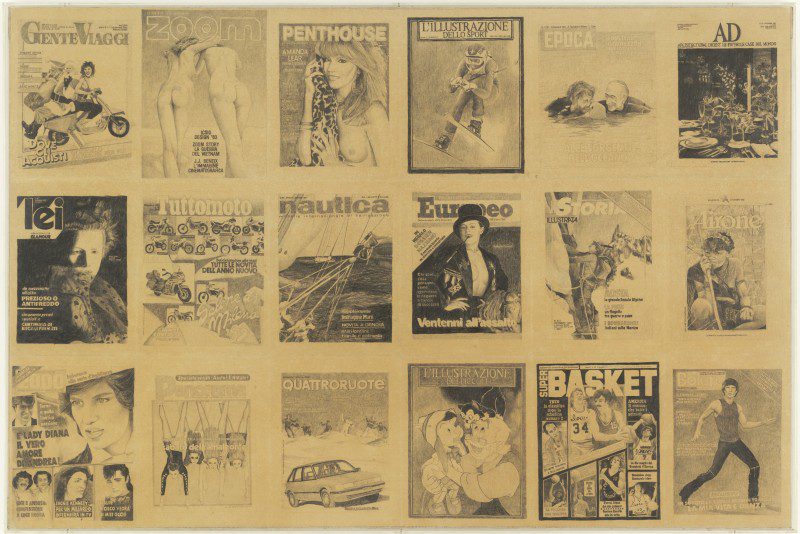

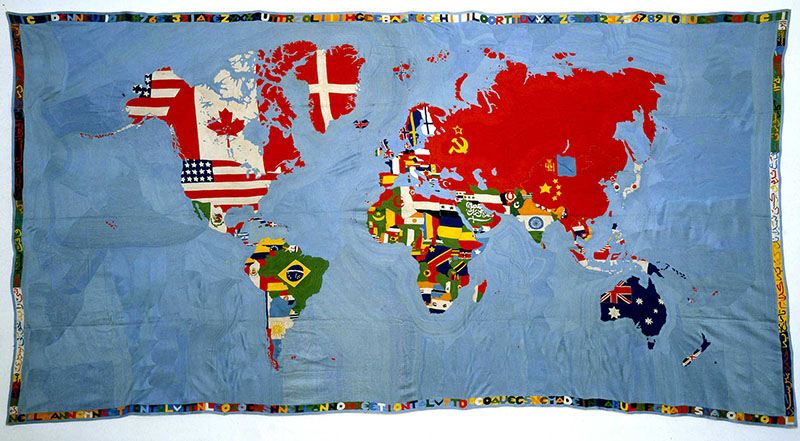

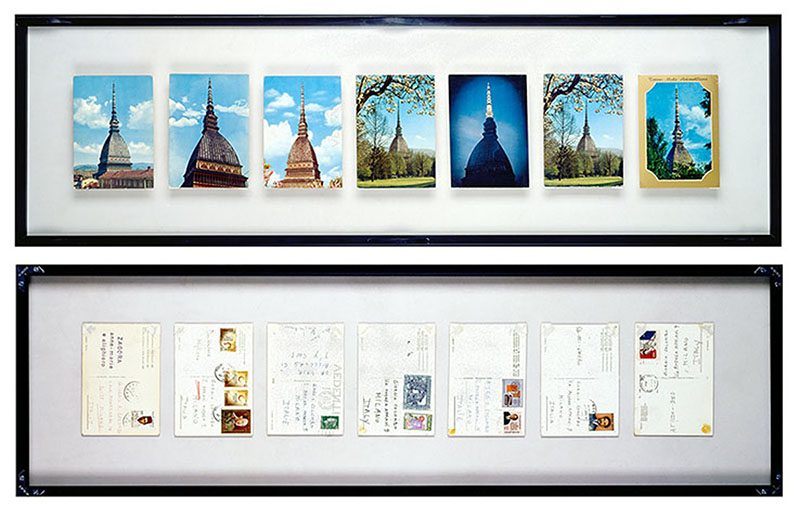

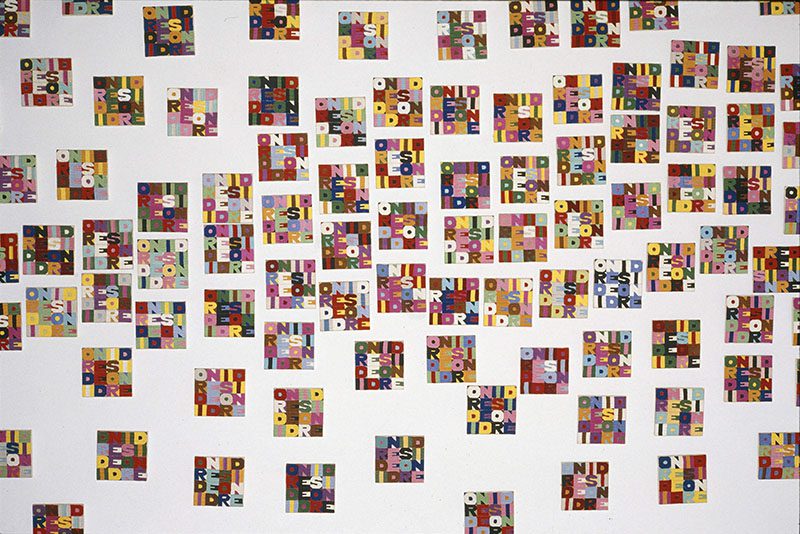

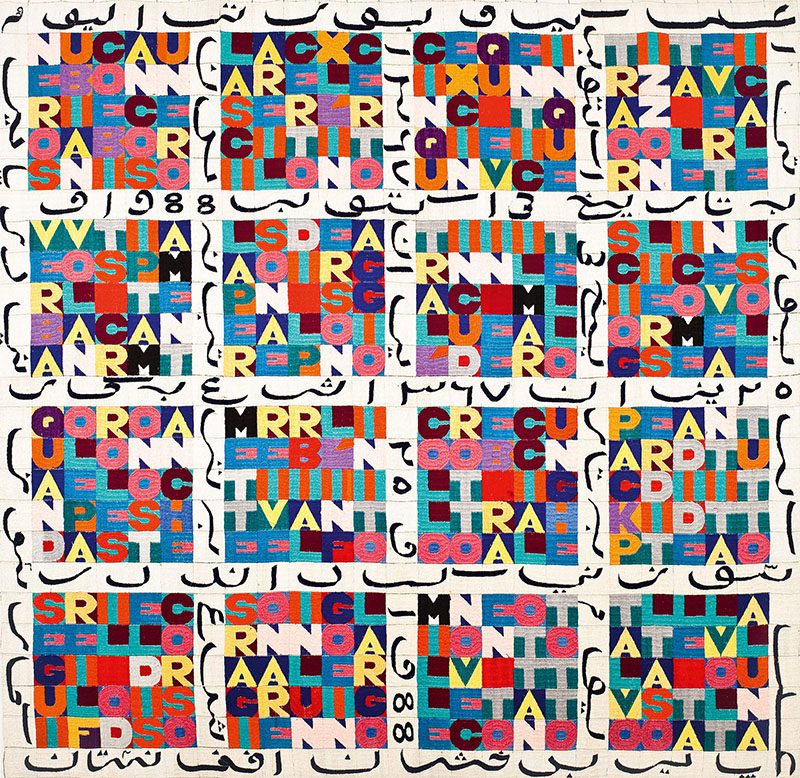

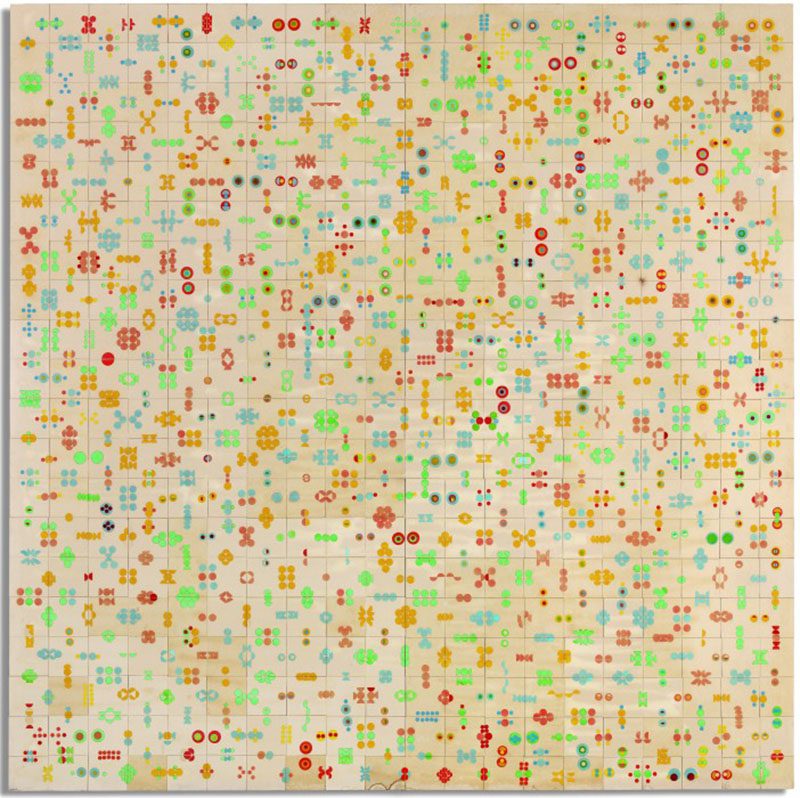

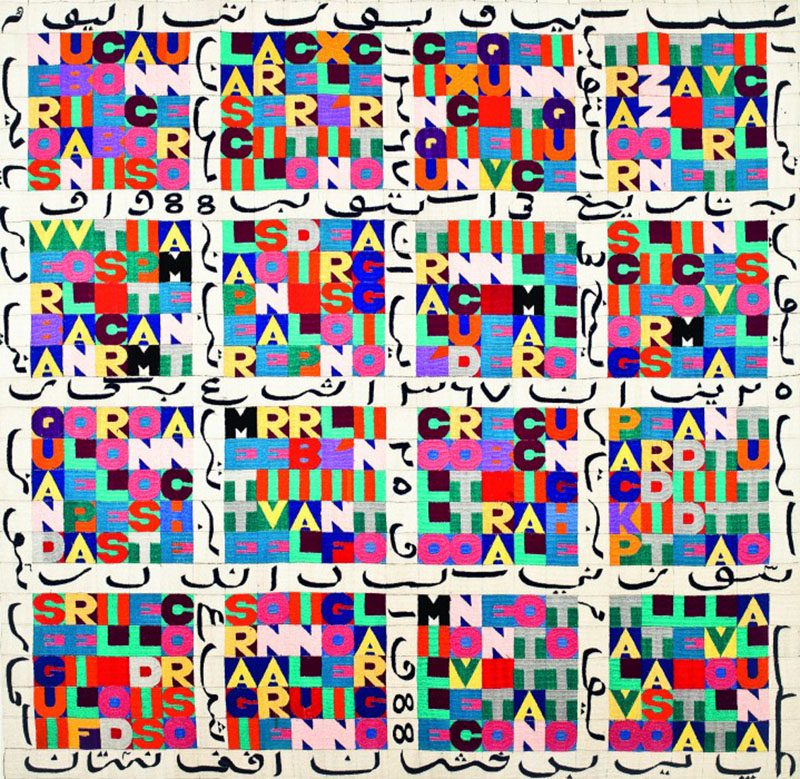

Alighiero Boetti was born in Turin, his artistic career begins in the second half of the ‘60s, when he abandoned his studies at the business school of the University of Turin to work as an artist.Working in his hometown in the early ‘60s amidst a close community of artists that included Luciano Fabro, Mario Merz, Giulio Paolini, and Michelangelo Pistoletto. After his first exhibition in 1967, he becomes associated with the Arte Povera Movement. An example of his Arte Povera work is “Lampada annual”, a single, outsized light bulb in a mirror-lined wooden box, which randomly switches itself on for eleven seconds each year. In 1967, Boetti produced “Manifesto”, a poster listing the names of artists that make up Boetti’s creative background. He was interested in oriental culture and other related disciplines, such as philosophy and alchemy. In 1971, he traveled to Afghanistan for the first time. He stayed there for one month and, through 1979 returned every year for longer periods of time. It is also in 1971 that he commissioned his first embroidered pictures, which are crafted by Afghani women. The production of these embroidered pictures continues until his death. The placing of texts and word into grid-like structures plays a special role in this process. The “Arazzi piccoli”, for example, are generally comprised of four by four, but often also of five by five or more squares of letters, which are embroidered in random colour combinations. Read from top to bottom, they reveal sayings such as “Dare tempo al tempo”, “Ordine e Disordine”, etc. The “Arazzi grandi”, on the other hand, are comprised of 25 x 25 squares of letters. “Twenty-five is the square of the holy number five and is therefore also the centre of magical squares. It consists of the sum of the numbers 1 + 3+ 5 + 7 + 9, and thus contains all the holy numbers which can be used in magic”. When he moved from Turin to Rome (1972), he became a pioneer and protagonist of the Conceptual Art in Italy, thanks also to his interests for philosophy, mathematics and alchemy. After a cold beginning close to the American Minimalism, Boetti switched to figurative solution which were tinged with irony and joyful chromatic elegance. Among the most widely known works by Alighiero Boetti are the embroidered maps of the world, which derive from conceptual works of the years 1967 to 1971. In September 1971, he took the first preliminary drawing to Afghanistan. Once the artist specified the colours of the threads to be used, four women then worked simultaneously on the embroidery, which, depending on the format, took between one and two years to complete. Also in the same period he began to sign as “Alighiero e Boetti”, this is the arrival point of a reflection on the splitting between reality and language, started in the ‘60s with the work “Gemelli”, a postcard where it is shown the artist who held hands with another himself, that was similar but not completely identical to him, while they are walking together on a tree-lined. Equally popular are Boetti’s “Lavori Biro”, the works in this group were executed with “common” ballpoint pens on paper, in the colours blue, black, red and green. Some of these were later mounted on canvas spanned on stretcher frames, while others were mounted on cardboard and placed in Plexiglas frames. At least with the earlier works, the artist asked the individuals working on the pictures to produce hatches which conformed as much as possible to a basic grid of small squares in order to make the technique used to create the pictures more visible. Later, the structures varied according to the individuals’ own patterns. “The extent of the delegated work varies from the minimum, as in the case of the Biro, where there is nothing creative to do at all, to the maximum, as in the case of the Tutto. I asked the assistants to draw everything, all possible forms, abstract and figurative, and to join these together until there was no space left on the paper. Then I brought the drawings to Afghanistan, where I had them embroidered with threads of ninety different colours, whereby I stipulated that the exact same amount of each colour had to be used”. In 1990 Boetti was invited at the Biennial of Venice with a personal room. From 1987 onwards, Boetti works together with his Iranian assistant Mahshid Mussari, who collected the most varied motif patterns for the realisation of the last and largest “Tutto”. After weeks of preparatory work, the oversized canvas could finally be sent to Peshawar in December 1993. After ten months, the completed work could finally be sent back to Rome, although Alighiero was never able to see it himself. He died in 1994 as a result of a brain tumour. In 2001, the Venice Pavillon was completely dedicated to Alighiero e Boetti’s work

Alighiero Boetti was born in Turin, his artistic career begins in the second half of the ‘60s, when he abandoned his studies at the business school of the University of Turin to work as an artist.Working in his hometown in the early ‘60s amidst a close community of artists that included Luciano Fabro, Mario Merz, Giulio Paolini, and Michelangelo Pistoletto. After his first exhibition in 1967, he becomes associated with the Arte Povera Movement. An example of his Arte Povera work is “Lampada annual”, a single, outsized light bulb in a mirror-lined wooden box, which randomly switches itself on for eleven seconds each year. In 1967, Boetti produced “Manifesto”, a poster listing the names of artists that make up Boetti’s creative background. He was interested in oriental culture and other related disciplines, such as philosophy and alchemy. In 1971, he traveled to Afghanistan for the first time. He stayed there for one month and, through 1979 returned every year for longer periods of time. It is also in 1971 that he commissioned his first embroidered pictures, which are crafted by Afghani women. The production of these embroidered pictures continues until his death. The placing of texts and word into grid-like structures plays a special role in this process. The “Arazzi piccoli”, for example, are generally comprised of four by four, but often also of five by five or more squares of letters, which are embroidered in random colour combinations. Read from top to bottom, they reveal sayings such as “Dare tempo al tempo”, “Ordine e Disordine”, etc. The “Arazzi grandi”, on the other hand, are comprised of 25 x 25 squares of letters. “Twenty-five is the square of the holy number five and is therefore also the centre of magical squares. It consists of the sum of the numbers 1 + 3+ 5 + 7 + 9, and thus contains all the holy numbers which can be used in magic”. When he moved from Turin to Rome (1972), he became a pioneer and protagonist of the Conceptual Art in Italy, thanks also to his interests for philosophy, mathematics and alchemy. After a cold beginning close to the American Minimalism, Boetti switched to figurative solution which were tinged with irony and joyful chromatic elegance. Among the most widely known works by Alighiero Boetti are the embroidered maps of the world, which derive from conceptual works of the years 1967 to 1971. In September 1971, he took the first preliminary drawing to Afghanistan. Once the artist specified the colours of the threads to be used, four women then worked simultaneously on the embroidery, which, depending on the format, took between one and two years to complete. Also in the same period he began to sign as “Alighiero e Boetti”, this is the arrival point of a reflection on the splitting between reality and language, started in the ‘60s with the work “Gemelli”, a postcard where it is shown the artist who held hands with another himself, that was similar but not completely identical to him, while they are walking together on a tree-lined. Equally popular are Boetti’s “Lavori Biro”, the works in this group were executed with “common” ballpoint pens on paper, in the colours blue, black, red and green. Some of these were later mounted on canvas spanned on stretcher frames, while others were mounted on cardboard and placed in Plexiglas frames. At least with the earlier works, the artist asked the individuals working on the pictures to produce hatches which conformed as much as possible to a basic grid of small squares in order to make the technique used to create the pictures more visible. Later, the structures varied according to the individuals’ own patterns. “The extent of the delegated work varies from the minimum, as in the case of the Biro, where there is nothing creative to do at all, to the maximum, as in the case of the Tutto. I asked the assistants to draw everything, all possible forms, abstract and figurative, and to join these together until there was no space left on the paper. Then I brought the drawings to Afghanistan, where I had them embroidered with threads of ninety different colours, whereby I stipulated that the exact same amount of each colour had to be used”. In 1990 Boetti was invited at the Biennial of Venice with a personal room. From 1987 onwards, Boetti works together with his Iranian assistant Mahshid Mussari, who collected the most varied motif patterns for the realisation of the last and largest “Tutto”. After weeks of preparatory work, the oversized canvas could finally be sent to Peshawar in December 1993. After ten months, the completed work could finally be sent back to Rome, although Alighiero was never able to see it himself. He died in 1994 as a result of a brain tumour. In 2001, the Venice Pavillon was completely dedicated to Alighiero e Boetti’s work