ARCHITECTURE: Le Corbusier

Formulated in 1926, Le Corbusier’s (6/10/1887-27/8/1965), “Five Points of a New Architecture” spearheaded the modernist architectural movement of the 20th century. As a prolific pioneer of the style, Le Corbusier famously allocated five essential points that dictated a new approach to the design of domestic architecture. The freedom afforded by the development of this new design vocabulary allowed for increased access to vast amounts of light, air, and space while creating uninterrupted openings in building facades and liberating the interior from the post and beam reinforced concrete structures within.

Formulated in 1926, Le Corbusier’s (6/10/1887-27/8/1965), “Five Points of a New Architecture” spearheaded the modernist architectural movement of the 20th century. As a prolific pioneer of the style, Le Corbusier famously allocated five essential points that dictated a new approach to the design of domestic architecture. The freedom afforded by the development of this new design vocabulary allowed for increased access to vast amounts of light, air, and space while creating uninterrupted openings in building facades and liberating the interior from the post and beam reinforced concrete structures within.

By Dimitris Lempesis

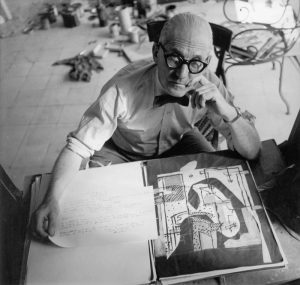

Le Corbusier was born Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris in La Chaux-de-Fonds, a small city in north-western Switzerland, in the Jura mountains. His family’s Calvinism, love of the arts and enthusiasm for the Jura Mountains, were all formative influences on the young Le Corbusier. At age 13, he left primary school to attend Arts Décoratifs at La Chaux-de-Fonds, where he would learn the art of enameling and engraving watch faces, following in the footsteps of his father. There, he fell under the tutelage of L’Eplattenier, whom Le Corbusier called “My master” and later referred to him as his only teacher. L’Eplattenier taught Le Corbusier art history, drawing and the naturalist aesthetics of art nouveau. Corbusier soon abandoned watchmaking and continued his studies in art and decoration, intending to become a painter. L’Eplattenier insisted that his pupil also study architecture, and he arranged for his first commissions working on local projects. After designing his first house, in 1907, Le Corbusier took trips through central Europe and the Mediterranean. His travels included apprenticeships with various architects, most significantly with structural rationalist Auguste Perret, a pioneer of reinforced concrete construction. In 1912, Le Corbusier returned to La Chaux-de-Fonds to teach alongside L’Eplattenier and to open his own architectural practice. He designed a series of villas and began to theorize on the use of reinforced concrete as a structural frame, a thoroughly modern technique. The floor plans of the proposed housing consisted of open space, leaving out obstructive support poles, freeing exterior and interior walls from the usual structural constraints. This design system became the backbone for most of Le Corbusier’s architecture for the next 10 years. In 1917, Le Corbusier moved to Paris, where he worked as an architect on concrete structures under government contracts. Then, in 1918, Le Corbusier met Cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant, who encouraged Le Corbusier to paint. Kindred spirits, the two began a period of collaboration in which they rejected cubism, an art form finding its peak at the time, as irrational and romantic. With these thoughts in mind, they published the book “Après le cubism”, an anti-cubism manifesto, and established a new artistic movement called purism. In 1920, the pair, along with poet Paul Dermée, established the purist journal “L’Esprit Nouveau”, an avant-garde review. In the first issue of the new publication, he took on the pseudonym Le Corbusier, an alteration of his grandfather’s last name, to reflect his belief that anyone could reinvent himself. In 1923, Le Corbusier published “Vers une Architecture”, which collected his polemical writing from L’Esprit Nouveau. In the book are such famous Le Corbusier declarations as “A house is a machine for living in” and “A curved street is a donkey track, a straight street, a road for men”. It was Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye (1929–31) that most succinctly summed up the five points of architecture that he had elucidated in L’Esprit Nouveau and the book “Vers une architecture”. First, Le Corbusier lifted the bulk of the structure off the ground, supporting it by pilotis, reinforced concrete stilts. These pilotis, in providing the structural support for the house, allowed him to elucidate his next two points, a free facade, meaning non-supporting walls that could be designed as the architect wished, and an open floor plan, meaning that the floor space was free to be configured into rooms without concern for supporting walls. The second floor of the Villa Savoye includes long strips of ribbon windows that allow unencumbered views of the large surrounding garden, and which constitute the fourth point of his system. The fifth point was the roof garden to compensate for the green area consumed by the building and replacing it on the roof. A ramp rising from ground level to the third-floor roof terrace allows for an architectural promenade through the structure. Le Corbusier’s collected articles also proposed a new architecture that would satisfy the demands of industry, hence functionalism, and the abiding concerns of architectural form, as defined over generations. His proposals included his first city plan, the Contemporary City, and two housing types that were the basis for much of his architecture throughout his life: the Maison Monol and, more famously, the Maison Citrohan, which he also referred to as “The machine of living”. Soon Le Corbusier’s social ideals and structural design theories became a reality. In 1925-1926, he built a workers’ city of 40 houses in the style of the Citrohan house at Pessac, near Bordeaux. Unfortunately, the chosen design and colors provoked hostility on the part of authorities, who refused to route the public water supply to the complex, and for six years the buildings sat uninhabited. In the 1930s, Le Corbusier reformulated his theories on urbanism, publishing them in “La Ville Radieuse” in 1935. The most apparent distinction between the Contemporary City and the Radiant City is that the latter abandoned the class-based system of the former, with housing now assigned according to family size, not economic position. The Radiant City brought with it some controversy, as all Le Corbusier projects seemed to. In describing Stockholm, for instance, a classically rendered city, Le Corbusier saw only “Frightening chaos and saddening monotony”. He dreamed of “Cleaning and purging the city with a calm and powerful architecture”. At the end of the 1930s and through the end of World War II, Le Corbusier kept busy with creating such famous projects as the proposed master plans for the cities of Algiers and Buenos Aires, and using government connections to implement his ideas for eventual reconstruction, all to no avail. After World War II, Le Corbusier attempted to realize his urban planning schemes on a small scale by constructing a series of “unités” (the housing block unit of the Radiant City) around France. The most famous of these was the Unité d’Habitation of Marseille (1946–52). In the 1950s, a unique opportunity to translate the Radiant City on a grand scale presented itself in the construction of the Union Territory Chandigarh, the new capital for the Indian states of Punjab and Haryana and India’s first planned city. Le Corbusier designed many administration buildings, including a courthouse, parliament building, and a university. He also designed the general layout of the city, dividing it into sectors. Le Corbusier was brought on to develop the plan of Albert Mayer. On 27/8/65, Le Corbusier went for a swim in the Mediterranean Sea at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France. His body was found by bathers It was assumed that he may have suffered a heart attack. His funeral took place in the courtyard of the Louvre Palace on 1/9/65, under the direction of André Malraux, who was at the time France’s Minister of Culture.

Le Corbusier was born Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris in La Chaux-de-Fonds, a small city in north-western Switzerland, in the Jura mountains. His family’s Calvinism, love of the arts and enthusiasm for the Jura Mountains, were all formative influences on the young Le Corbusier. At age 13, he left primary school to attend Arts Décoratifs at La Chaux-de-Fonds, where he would learn the art of enameling and engraving watch faces, following in the footsteps of his father. There, he fell under the tutelage of L’Eplattenier, whom Le Corbusier called “My master” and later referred to him as his only teacher. L’Eplattenier taught Le Corbusier art history, drawing and the naturalist aesthetics of art nouveau. Corbusier soon abandoned watchmaking and continued his studies in art and decoration, intending to become a painter. L’Eplattenier insisted that his pupil also study architecture, and he arranged for his first commissions working on local projects. After designing his first house, in 1907, Le Corbusier took trips through central Europe and the Mediterranean. His travels included apprenticeships with various architects, most significantly with structural rationalist Auguste Perret, a pioneer of reinforced concrete construction. In 1912, Le Corbusier returned to La Chaux-de-Fonds to teach alongside L’Eplattenier and to open his own architectural practice. He designed a series of villas and began to theorize on the use of reinforced concrete as a structural frame, a thoroughly modern technique. The floor plans of the proposed housing consisted of open space, leaving out obstructive support poles, freeing exterior and interior walls from the usual structural constraints. This design system became the backbone for most of Le Corbusier’s architecture for the next 10 years. In 1917, Le Corbusier moved to Paris, where he worked as an architect on concrete structures under government contracts. Then, in 1918, Le Corbusier met Cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant, who encouraged Le Corbusier to paint. Kindred spirits, the two began a period of collaboration in which they rejected cubism, an art form finding its peak at the time, as irrational and romantic. With these thoughts in mind, they published the book “Après le cubism”, an anti-cubism manifesto, and established a new artistic movement called purism. In 1920, the pair, along with poet Paul Dermée, established the purist journal “L’Esprit Nouveau”, an avant-garde review. In the first issue of the new publication, he took on the pseudonym Le Corbusier, an alteration of his grandfather’s last name, to reflect his belief that anyone could reinvent himself. In 1923, Le Corbusier published “Vers une Architecture”, which collected his polemical writing from L’Esprit Nouveau. In the book are such famous Le Corbusier declarations as “A house is a machine for living in” and “A curved street is a donkey track, a straight street, a road for men”. It was Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye (1929–31) that most succinctly summed up the five points of architecture that he had elucidated in L’Esprit Nouveau and the book “Vers une architecture”. First, Le Corbusier lifted the bulk of the structure off the ground, supporting it by pilotis, reinforced concrete stilts. These pilotis, in providing the structural support for the house, allowed him to elucidate his next two points, a free facade, meaning non-supporting walls that could be designed as the architect wished, and an open floor plan, meaning that the floor space was free to be configured into rooms without concern for supporting walls. The second floor of the Villa Savoye includes long strips of ribbon windows that allow unencumbered views of the large surrounding garden, and which constitute the fourth point of his system. The fifth point was the roof garden to compensate for the green area consumed by the building and replacing it on the roof. A ramp rising from ground level to the third-floor roof terrace allows for an architectural promenade through the structure. Le Corbusier’s collected articles also proposed a new architecture that would satisfy the demands of industry, hence functionalism, and the abiding concerns of architectural form, as defined over generations. His proposals included his first city plan, the Contemporary City, and two housing types that were the basis for much of his architecture throughout his life: the Maison Monol and, more famously, the Maison Citrohan, which he also referred to as “The machine of living”. Soon Le Corbusier’s social ideals and structural design theories became a reality. In 1925-1926, he built a workers’ city of 40 houses in the style of the Citrohan house at Pessac, near Bordeaux. Unfortunately, the chosen design and colors provoked hostility on the part of authorities, who refused to route the public water supply to the complex, and for six years the buildings sat uninhabited. In the 1930s, Le Corbusier reformulated his theories on urbanism, publishing them in “La Ville Radieuse” in 1935. The most apparent distinction between the Contemporary City and the Radiant City is that the latter abandoned the class-based system of the former, with housing now assigned according to family size, not economic position. The Radiant City brought with it some controversy, as all Le Corbusier projects seemed to. In describing Stockholm, for instance, a classically rendered city, Le Corbusier saw only “Frightening chaos and saddening monotony”. He dreamed of “Cleaning and purging the city with a calm and powerful architecture”. At the end of the 1930s and through the end of World War II, Le Corbusier kept busy with creating such famous projects as the proposed master plans for the cities of Algiers and Buenos Aires, and using government connections to implement his ideas for eventual reconstruction, all to no avail. After World War II, Le Corbusier attempted to realize his urban planning schemes on a small scale by constructing a series of “unités” (the housing block unit of the Radiant City) around France. The most famous of these was the Unité d’Habitation of Marseille (1946–52). In the 1950s, a unique opportunity to translate the Radiant City on a grand scale presented itself in the construction of the Union Territory Chandigarh, the new capital for the Indian states of Punjab and Haryana and India’s first planned city. Le Corbusier designed many administration buildings, including a courthouse, parliament building, and a university. He also designed the general layout of the city, dividing it into sectors. Le Corbusier was brought on to develop the plan of Albert Mayer. On 27/8/65, Le Corbusier went for a swim in the Mediterranean Sea at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France. His body was found by bathers It was assumed that he may have suffered a heart attack. His funeral took place in the courtyard of the Louvre Palace on 1/9/65, under the direction of André Malraux, who was at the time France’s Minister of Culture.