ART CITIES: Tokyo-Christian Marclay

Christian Marclay, musician, composer and visual artist, explores the connections between sound, photography, video, and film. A pioneer in the instrumental use of turntables to create sound collages, Christian Marclay is, in the words of critic Thom Jurek, perhaps “the unconscious inventor of turntablism” His use of turntables began in the mid-1970s, but this development was independent of that of hip-hop. Indeed, Christian Marclay comes more from the Rock and Punk cultures of the 1970s, questioning and criticizing the commercial use of vinyl records and the cultural industries.

Christian Marclay, musician, composer and visual artist, explores the connections between sound, photography, video, and film. A pioneer in the instrumental use of turntables to create sound collages, Christian Marclay is, in the words of critic Thom Jurek, perhaps “the unconscious inventor of turntablism” His use of turntables began in the mid-1970s, but this development was independent of that of hip-hop. Indeed, Christian Marclay comes more from the Rock and Punk cultures of the 1970s, questioning and criticizing the commercial use of vinyl records and the cultural industries.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: MOT Archive

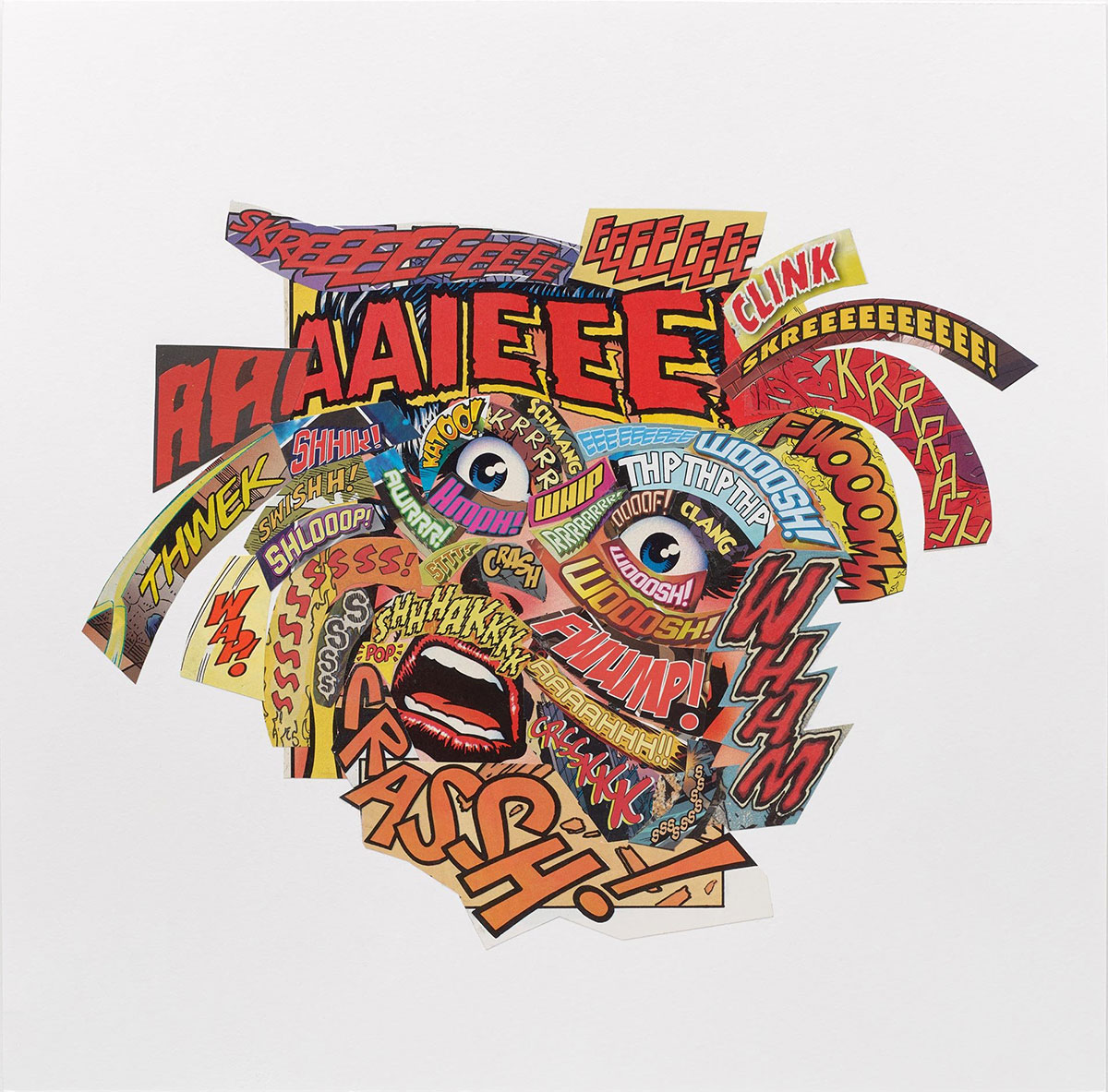

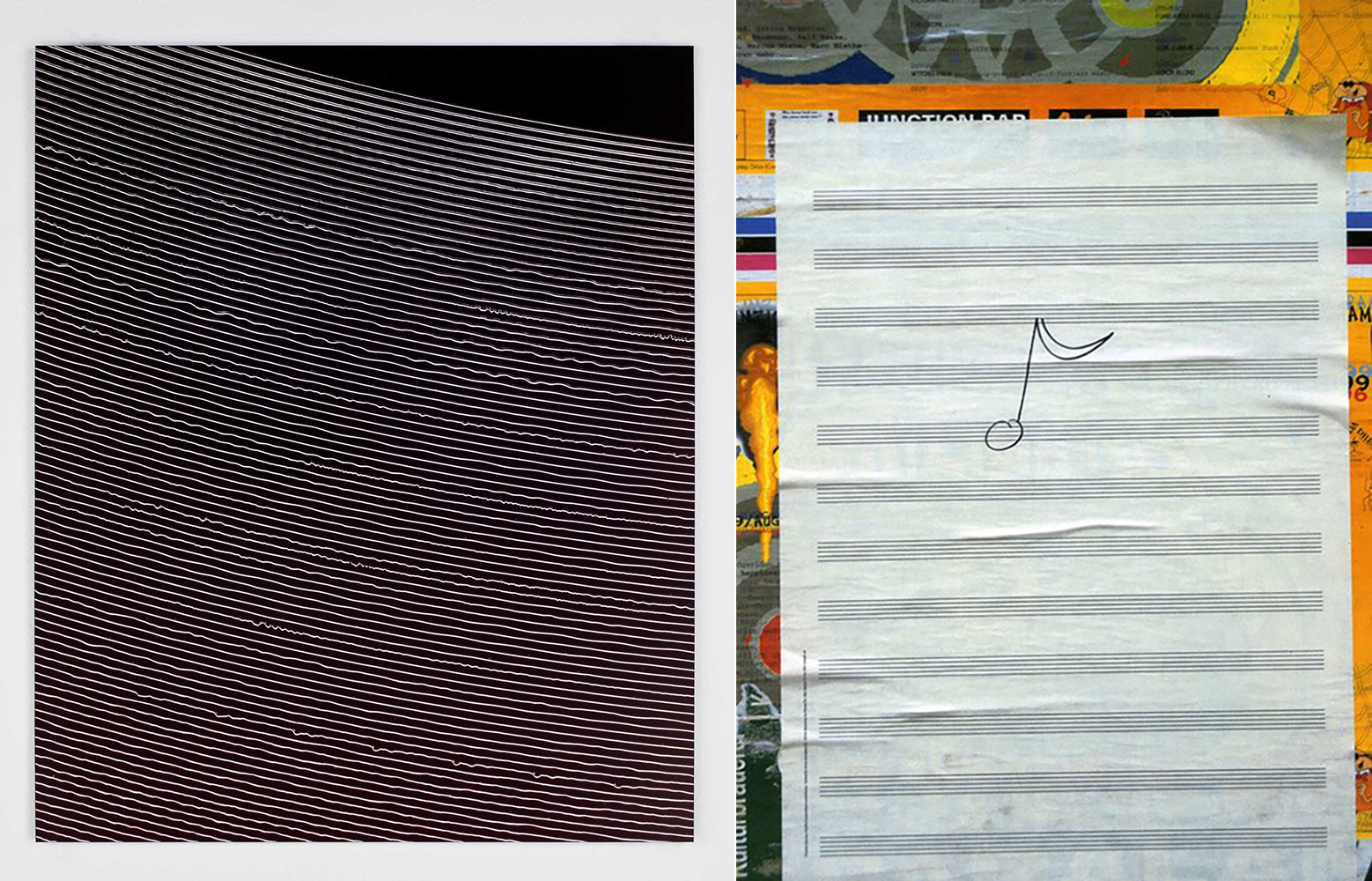

“Translating” is the first large-scale solo exhibition of the Christian Marclay’s work in a Japanese museum and aims to introduce his diverse and eclectic practice to audiences. Sampling his oeuvre, it includes early works, influenced by conceptual art and punk music, large-scale installations built from samples of image and sound information, and more recent works that reflect upon the anxieties permeating our contemporary world. Marclay’s technique of sampling, evident in many of his works, entails extracting and repurposing existing images and sounds, and can be considered an act of “translation” from one realm to the other, offering an alternative to language. Whether using the materiality of recorded sound to create images, as in his celebrated series of photograms, or translating image back into sound, as with the creation of “graphic scores” in which images from our day-to-day environment are given over to musicians as scores from which to create music, Marclay’s practice exists at the intersection of these two cultural forms. The exhibition will also include works that feature onomatopoeia, appropriated from manga comics originally published in Japan and translated into English, such as “Magna Scroll” (2010) which is a vocal “graphic score”. Shifting back and forth between sound and vision, everyday objects and art, information and matter, as well as different cultures, Marclay’s practice explores the creative possibilities and contradictions inherent in translation. With a keen eye (and ear) and understated humor, he draws attention to the sensations and perceptions we take for granted while revealing the precariousness of human communication. In his work as a turntablist, Marclay used multiple turntables to play records and interact with other improvising musicians. Not only did he physically alter the records, often marking them with markers or stickers to help finding sounds during performances, he also made collages by cutting the vinyl discs, slicing and pasting together record fragments as if they were pieces of a puzzle. When actually played, these collages give rise to unexpected musical compositions. “Recycled Records”, made as a series between 1979 and 1986, contradict the idea of the record as a multiple mass-produced object. Here it is reborn as a hand-made, unique, one-of-a-kind record that never plays the same twice. In 1979, Marclay formed a band called The Bachelors, Even (quoting The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even by Marcel Duchamp), which fused together influences ranging from post-punk to Fluxus performance and beyond. Marclay’s use of records and turntables as musical instruments attracted attention in a completely different way than the hip-hop scene, which was on the rise at the time. The idea to treat the record as a musical instrument evolved into one of Marclay’s earliest video work, a recording of his own performance. In “Fast Music” (1992) he is seen eating a vinyl record using stop motion animation. In “Record Players” (1984), Marclay orchestrates acoustic sounds made with LPs: hitting, bending, breaking. Marclay asks the audience to listen to the record itself, not the sound captured in its grooves. His deejay performance also repositions the record as an object to create live music in the present, not in the past recorded in its grooves. In the early 1980s, Marclay went around various thrift stores and built up a collection of used and unwanted records costing less than a dollar. The cover designs and illustrations of these records inspired him to imagine music that he had never heard before. The “Imaginary Records” (1988-97) series explores the possibilities of such record covers to evoke music. Marclay altered and remixed the record covers, for example, by taking the title from one album and embedding it into a different cover, or erasing the background altogether. In some cases, his alterations allude to the presence of hidden themes like death and rebirth. In the context of Marclay’s practice, records are “lifeless recordings” of “live music,” making them a medium that invokes a two-way metamorphosis between life and death. “Record Without a Cover” was released in 1985 with no cover or protective packaging. Thus the accidental damages from shipping and handling became part of the work, as “noise” blending with the original recording. The more one plays the record, the more the record’s condition and sound undergo further transformations, accepting its own entropy and bringing together both past and present. In the music industry, “noise” is something that should be eliminated at all points of the production process, from recording to distribution. For Marclay the noise created by the damaged vinyl is a positive element that allows unpredictable outcomes. A reissue of “Record Without a Cover” was released in 1999 by the Japanese label Locus Solus. Marclay created the series of works “Project for the Recycling Plant”, made from various used electronic goods and discarded urban waste, for an exhibition held at a recycling plant in Tokyo in 2005. For Marclay, who gained inspiration for his early deejay practice when he came across an abandoned record on the street while a student in Boston, garbage is a state that strips an object from its original function down to its raw materials. Here, Marclay documents the recycling process that breaks down the electronic equipment into its separate material components. The audience can see and hear the process on the same devices that are being recycled, as a kind of musical composition generated by chance. Marclay overlays the multiple transformation of these unwanted, discarded objects and gives them new life as visually and sonically stimulating artworks. They are also self-referential explorations of the object itself. In the suite of works on paper titled Studies for Variations on a Silence, made in preparation for his Recycling Plant project, Marclay moves documents around on a copy machine to distort and print over the previous copies, layering information and forming not a copy, but a unique print. “Ephemera: A Musical Score” (2009): Fragments of Marclay’s eclectic collection of newspaper advertisements, magazine illustrations, restaurant menus, candy wrappers, and other disposable printed matter decorated with musical notations were photographed and reproduced as twenty-eight unbound prints. These images constitute a score that can be organized and interpreted using one or more instruments. Marclay sheds a fleeting light on these ephemeral objects—not meant to be retained or preserved, but used for only a short time. These short-lived images remind us of how, before recording equipment existed, music captured the hearts of so many precisely because of the way it vanishes the moment of its birth. “No!” (2020) is a portfolio of 15 prints made from collages using comic book fragments, and conceived as a graphic score for a solo voice. Unlike “Manga Scroll”, which is a composition consisting of onomatopoeias disconnected from their generative actions, this work shows more of the context in which these fragments were sampled from, thus prompting the performers to present a rendition of the emotional states and body movements illustrated. The resulting work superimposes many meanings, including political and social circumstances, onto the primal human expression of resistance, “no!”, while enabling us to experience shared emotions, the fundamental function of music.

Photo: Christian Marclay, Recycling Circle, 2005, video installation with sounds, Photo: Osamu Watanabe, © Christian Marclay. Courtesy Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo

Info: Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (MOT) , 4-1-1 Miyoshi, Koto-ku, Tokyo, Japan, Duration: 20/11/2021-23/2/2022, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, www.mot-art-museum.jp

Right: Christian Marclay, Continental (from the series ‘Body Mix’), 1991, 2 record covers and cotton thread 54.6㎝ x 33 cm, Photo: Steven Probert, © Christian Marclay. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Right: Christian Marclay, Scream (Orange and Blue Shaking), 2019, color woodcut 220.1㎝ x 121.5 cm, © Christian Marclay. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Right: Christian Marclay, Untitled from Graffiti Composition,1996-2002, detail from portfolio of 150 prints, © Christian Marclay. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York