ART CITIES:N.York-Neil Jenney

Neil Jenney is committed to exploring, and ultimately transcending, realism as both style and philosophy, a project first sparked by the preponderance of Pop-themed Photorealism in late-1960s New York. Having designated his early work “Bad Painting” (a term coined by Marcia Tucker, director of the New Museum, New York, in 1978) and his output after 1970 “Good Painting,” he continues to challenge familiar models of taste and subject matter while pursuing a meticulous and highly idiosyncratic approach to the representation of culture and place.

Neil Jenney is committed to exploring, and ultimately transcending, realism as both style and philosophy, a project first sparked by the preponderance of Pop-themed Photorealism in late-1960s New York. Having designated his early work “Bad Painting” (a term coined by Marcia Tucker, director of the New Museum, New York, in 1978) and his output after 1970 “Good Painting,” he continues to challenge familiar models of taste and subject matter while pursuing a meticulous and highly idiosyncratic approach to the representation of culture and place.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo; Gagosian Archive

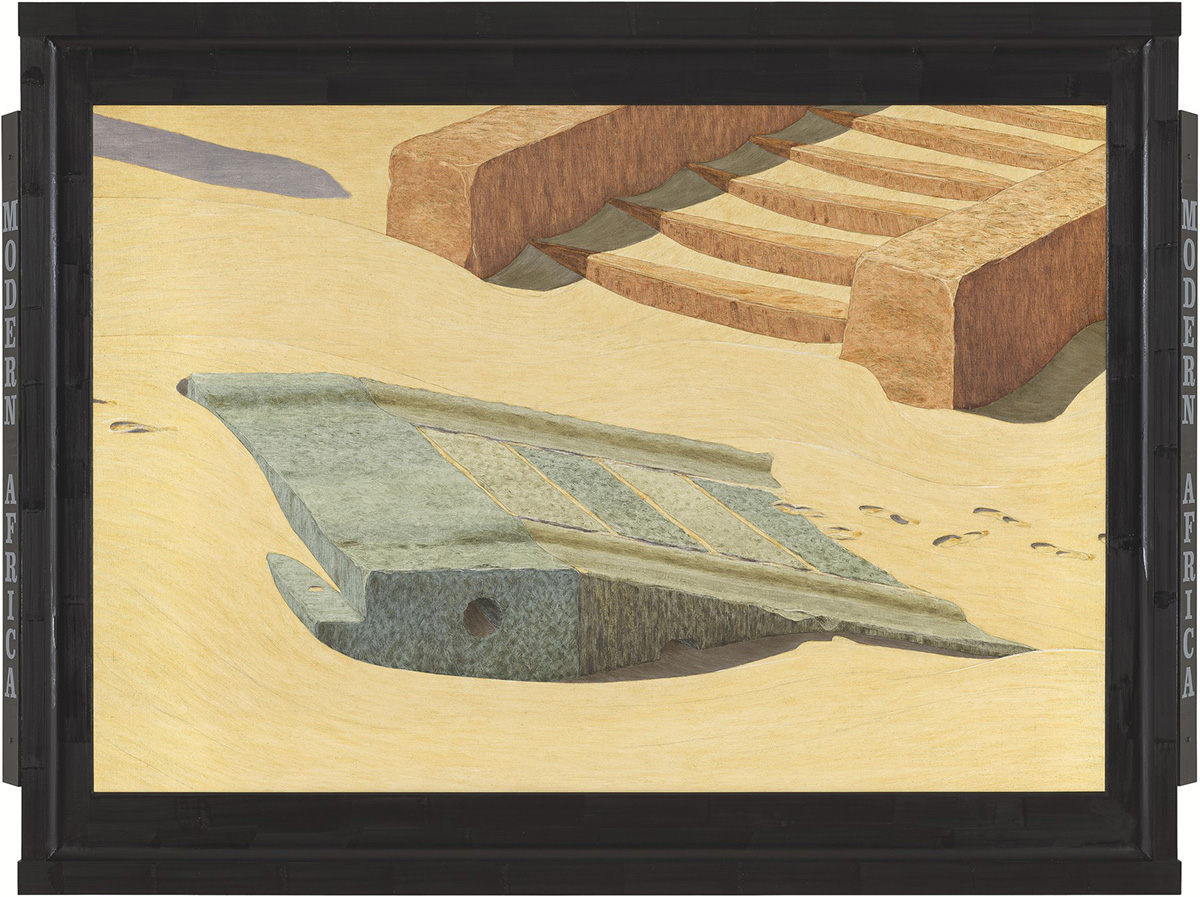

Neil Jenney in his solo exhibition “American Realism Today” presents paintings from his series “Modern Africa “(2015– ) a subseries of the “New Good Paintings” (2015– ) and the preceding series, “Good Paintings” (1971–2015). “Modern Africa” shows architectural fragments that Jenney characterizes as “utilitarian”—columns, ramps, and stairways—half-submerged in undulating sand dunes. These monumental structures seem to exist in past and future simultaneously, providing both a critical look at the legacies of colonialism and a speculative view of what may lie in wait for humanity should we fail to address climate change. While the shadows and footprints that intrude here and there reveal a continued human presence, no figures are visible, suggesting that Jenney’s envisioned world is incapable of supporting many survivors. Jenney refers to his work as “painted sculpture” and uses handmade black wooden frames, which he first designed in the early 1970s, to present canvases executed in a crisp, high-contrast style. This device was inspired by the classical Greek notion of viewing a painting as a scene through a window, an idea that he encountered in a Fourth Avenue bookstore. Providing in this way an “architectural foreground” as well as—through their stenciled captions—a guide to title and setting, the frames situate the paintings as objects and interpretations and continue to provide Jenney with what he has described as “the most stimulating prospect” with which he has ever worked.

In his two years at Massachusetts College of Art, Boston, from 1964 to 1966, Neil Jenney created hard-edge paintings and Minimalist sculpture, showing an advanced understanding of contemporary art. Yet when he was ready, his work was rejected by all Boston galleries. This disappointment forced Jenney to realize that selling art was not a financial solution in Boston, and that he couldn’t afford being a student. As the few part-time jobs were already taken, gone was the notion of working his way through school. On November 6, 1966, Jenney turned twenty-one and started driving a checker cab for Town Taxi, which he would do full-time for sixty-three days straight. On or about January 7, 1967, he moved to 723 East 6th Street, New York, and began his “Anti-Minimal Sculpture”, initially with an “Electric Light Piece” that drained his funds and was never completed. Next came the “Linear Series” groups of half-inch aluminum bars, coated with a flexible multicolored paint and arranged on the floor. These pieces featured a new Anti-Minimal element: the random crooked line. Jenney next restated the concept with The Volumetric Series: irregularly shaped masses of fabric, formed over chicken wire and arranged in groups of three or four on the floor. Jenney’s dealer, Richard Bellamy, sold the best Volumetric to Robert Scull in the spring of 1967, in Jenney’s first New York sale, for $300.

Next came the Found (free) Material Series, large floor arrangements critically referred to as “environmental,” “theatrical,” or “maximal.” However, as critics were beginning to identify Jenney as an “earth” or “environmental” artist, he was growing discouraged with the lack of sales, despite some nice comments made. One day Bellamy said, “Well, ya know, Jenney, nobody’s got floor space—everybody’s got wall space.” So Jenney put some Linear Pieces on the wall and made some sales! Bellamy was right. Jenney needed wall ideas. Now the format of the “environmental” Found Material Pieces of 1968 gradually mutated to a simple structure of “these things and those things relating”: tanks of circulating water and plants (1968), shown at Noah Goldowsky/Richard Bellamy Gallery, New York, spring of 1968; a desk and office chair with lighted neon on top (1968), shown in West Germany at Galerie Rudolf Zwirner, November 1968; soapy water in hanging vinyl containers and washed wood (1968), shown at Galerie Rudolf Zwirner, November 1968; two corrugated aluminum structures with three fluorescent lights (1968), shown at David Whitney Gallery, New York, November 1970. Jenney’s life was looking in dumpsters every day, as he couldn’t afford materials. Often he couldn’t find what he was looking for, and often the good stuff was under a pile of other stuff and couldn’t be retrieved. This made art making slow and frustrating. At some point Jenney mused that if he was doing paintings he could just paint whatever he needed, and that the paintings would be on the wall, where the money was. And that “things relating to other things, not just spatially, but through their identity as objects” (the structural format of the sculptures) could be stated in painting form. And that this brand of realism was very removed from the Pop art, straight American symbolism solution of the day.

Jenney reckoned that Pop art was “veneration of the superficial”—Campbell’s Soup, movie stars, pickup trucks, storefronts, American stuff. Jenney felt that the world was ready for veneration of the relevant, the pertinent, the profound, the timely. No one was dealing with these elements; they were just laying there, like electricity was in 1840. So it was now painting. Jenney decided to deliver the message as directly as possible, drawing and painting once only, using acrylic paint. This brand of new realism began in 1969 and finished in 1970. These works featured relating elements isolated on large areas of canvas, painted green (grass), blue (sky/water), or brown (dirt or tabletop). The work developed in three stages. The first paintings were made as part of the last “environmental” sculpture, and were shown in 1969 at the new Whitney Museum in a show called Anti-Illusion: two series of paintings with images in cinematic progression on the wall, plus dog food in food bowls on newspapers on the floor. Jenney quickly realized that a single-image statement was the most practical. Stage two: these first single-image works started with quick drawing and fast painting. The results were rather sloppy—but the message was clear. In December 1970 Jenney decided to tackle the oil pigment puzzle. And to move past the “this and that” format of the Bad years, and to work on wood, which would allow for greater precision. This led Jenney first to the library, to seek books with technical answers and the secrets of the ancients. Here he learned of the Greek notion that a painting was a scene viewed through a window, hence the window (the frame) presented the illusion and existed as the architectural foreground. So frames were functional.

Jenney had avoided framing the Bad Paintings of 1969–70, thinking that frames were merely decoration, and figured that prettifying Bad Painting would diminish its purity. Wrong paintings require a frame, and it’s a perfect place for the title. This revelation was the most sustaining inspiration that Jenney ever had, as suddenly he was back in the sculpture business again, where he felt most comfortable. Since 1971 Jenney has not stopped drawing frames. He started with the Bad Painting solution, and since that date has developed nine distinct framing solutions, some featuring innovations like the seamless face with the lighted surface treatment; some with a mantled base, or big lintel, or wide side face, or most recently the narrow/wide face; some using side-mounted titles, others using the marquee-style (angled) side titles. Jenney designated all works from 1971 on—all on wooden surfaces—as Good Painting. These works focused on the “intimate,” rather than the “panoramic.” And Jenney now refers to the early new realism of the 1960s as Bad Painting, thanks to Marcia Tucker. At some point the oil-on-wood works—with the frames—became rather heavy, too difficult to move without assistance. This annoyed Jenney, as he preferred to do things himself. Jenney’s assistant Romeo (Joe) DeTullio (frame maker) passed on in 2004, age eighty-nine years. One day Jenney mused—after some thirty years—that he had never painted on canvas with oils, and that work on canvas would be much lighter. And that even bigger works could be moved by himself alone. The first of these works came from old drawings for paintings never done. Jenney refers to these new works (2016) as the New Good Paintings, as they have a different process entirely.

Photo: Neil Jenney, Modern Africa #1, 2015–16 Oil on canvas, in painted wood artist’s frame, 67 × 97 × 3 ¼ inches (170.2 × 246.4 × 8.3 cm), © Neil Jenney, Photo: Rob McKeever, Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

Info: Gagosian Gallery, 976 Madison Avenue, New York, NY, USA, Duration: 9/11-18/12/2021, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10;00-18:00, https://gagosian.com