TRACES: On Kawara

Today is the occasion to bear in mind one of the most enigmatic artists, On Kawara (24/12/19/1932-10/7/2014). His process-based art practice, which made use of materials such as postcards, telegrams, maps, and calendars, opened doors for other Conceptual artists seeking to redefine their practices beyond the canvas, and for the integration of ephemeral media into the fine arts. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind one of the most enigmatic artists, On Kawara (24/12/19/1932-10/7/2014). His process-based art practice, which made use of materials such as postcards, telegrams, maps, and calendars, opened doors for other Conceptual artists seeking to redefine their practices beyond the canvas, and for the integration of ephemeral media into the fine arts. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

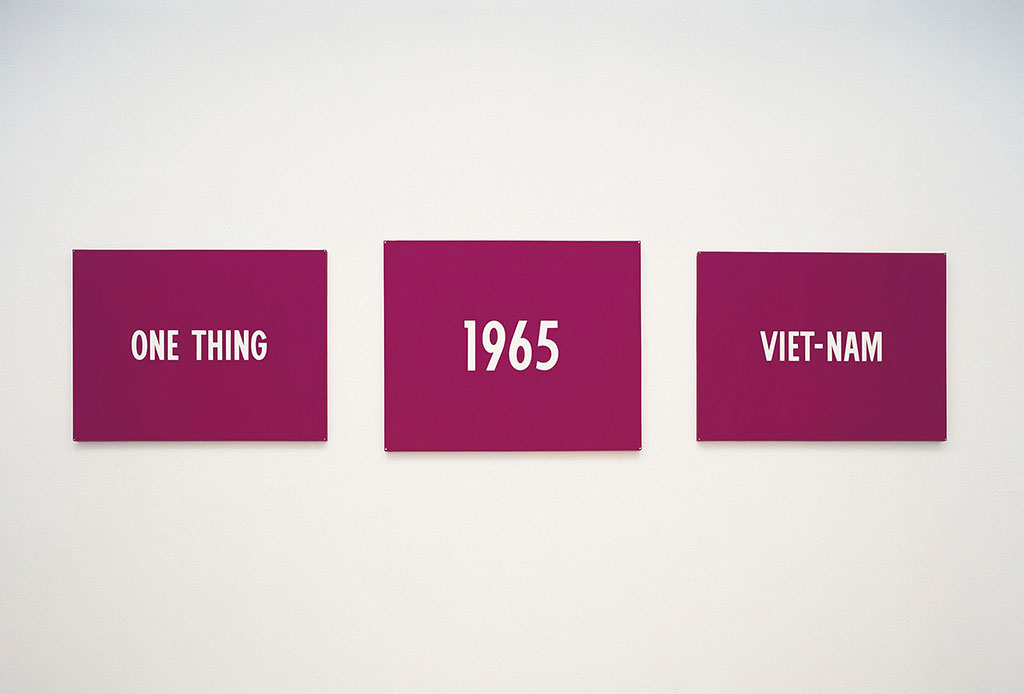

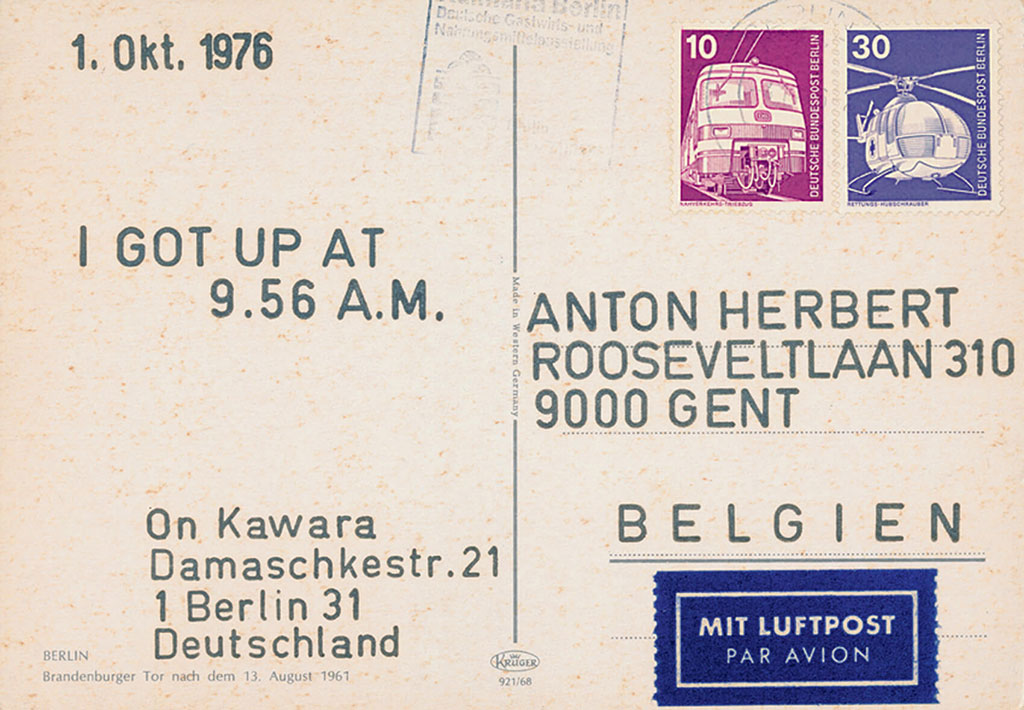

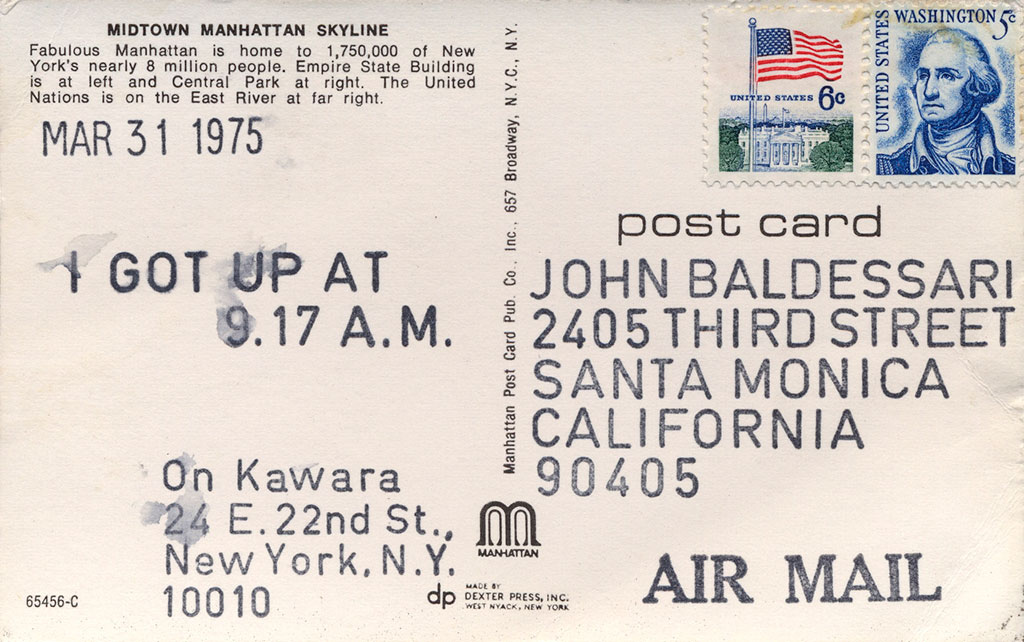

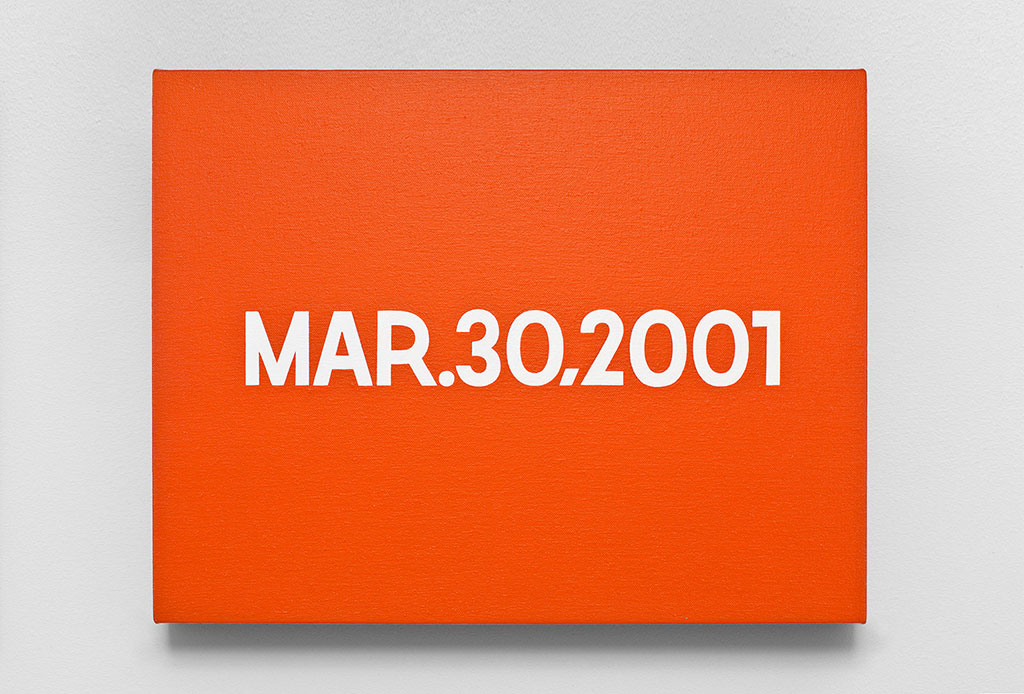

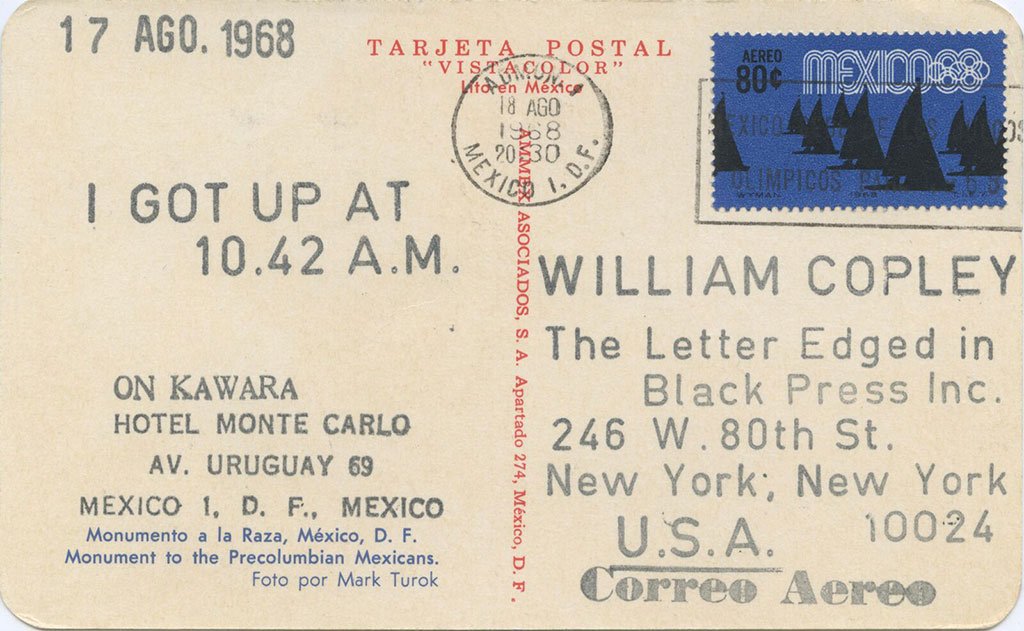

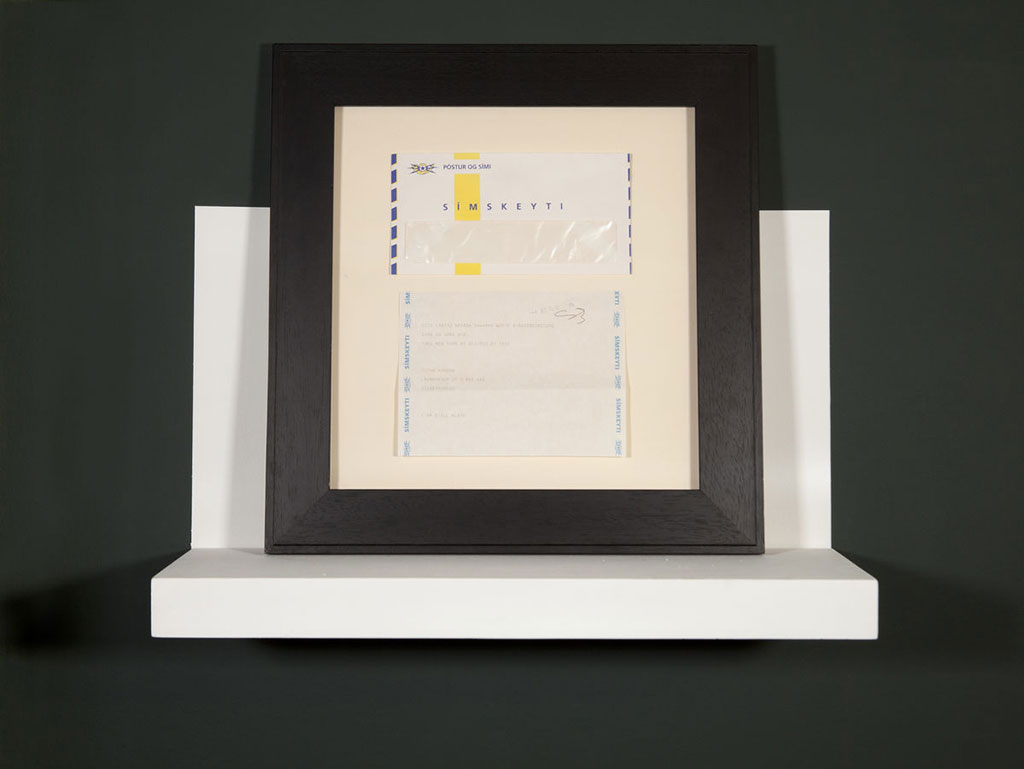

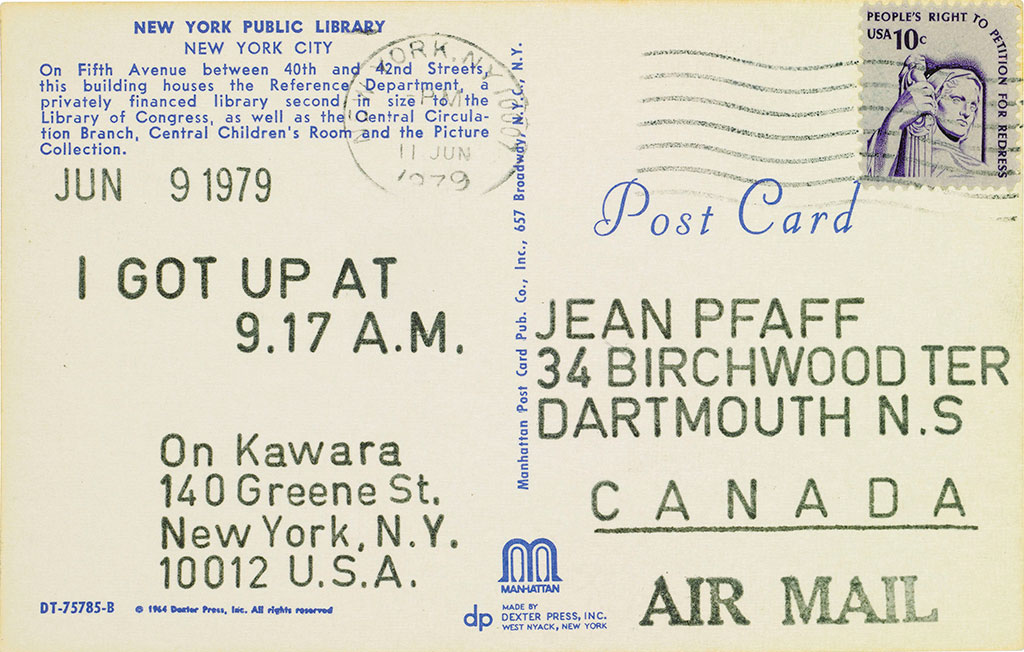

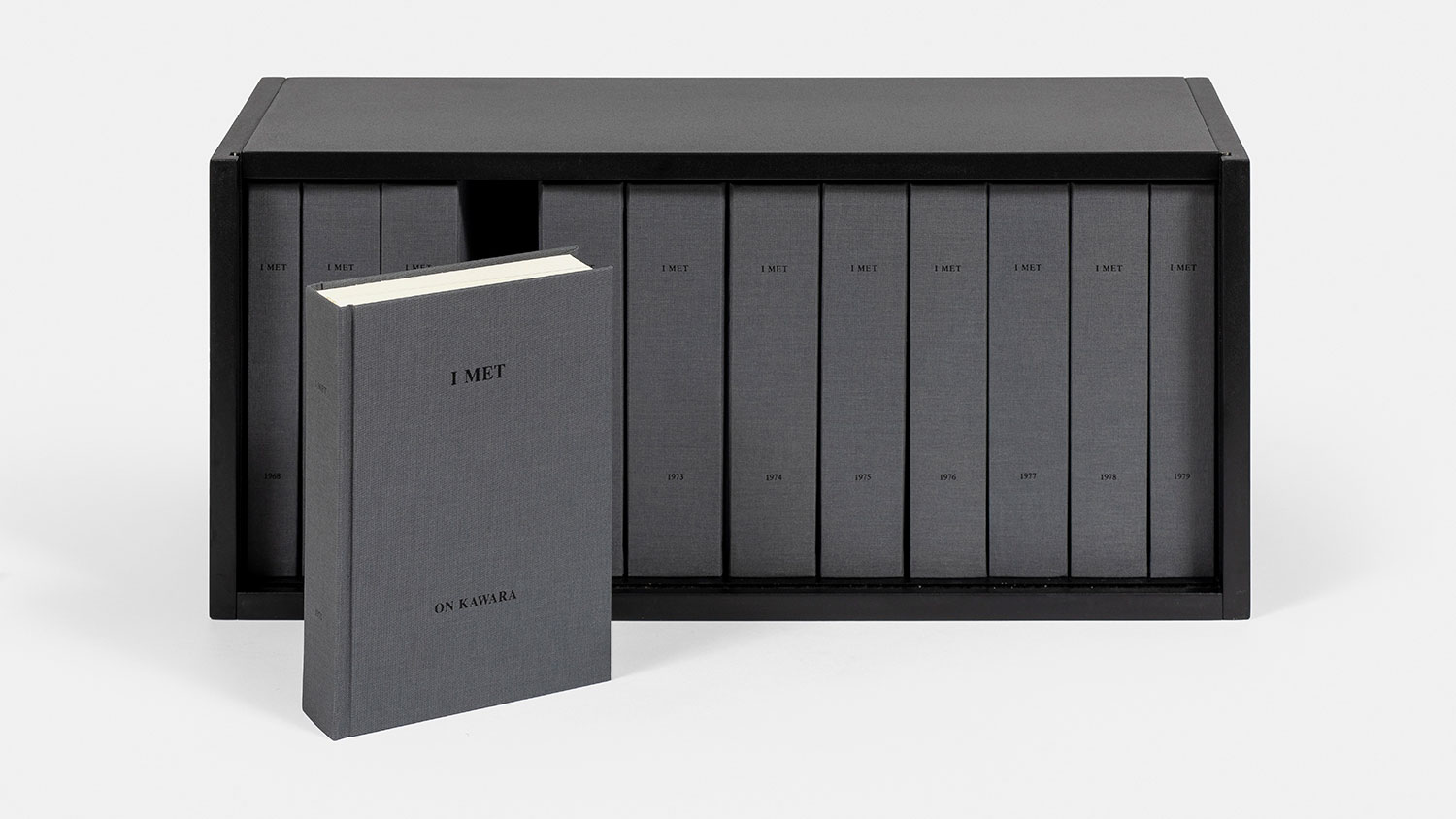

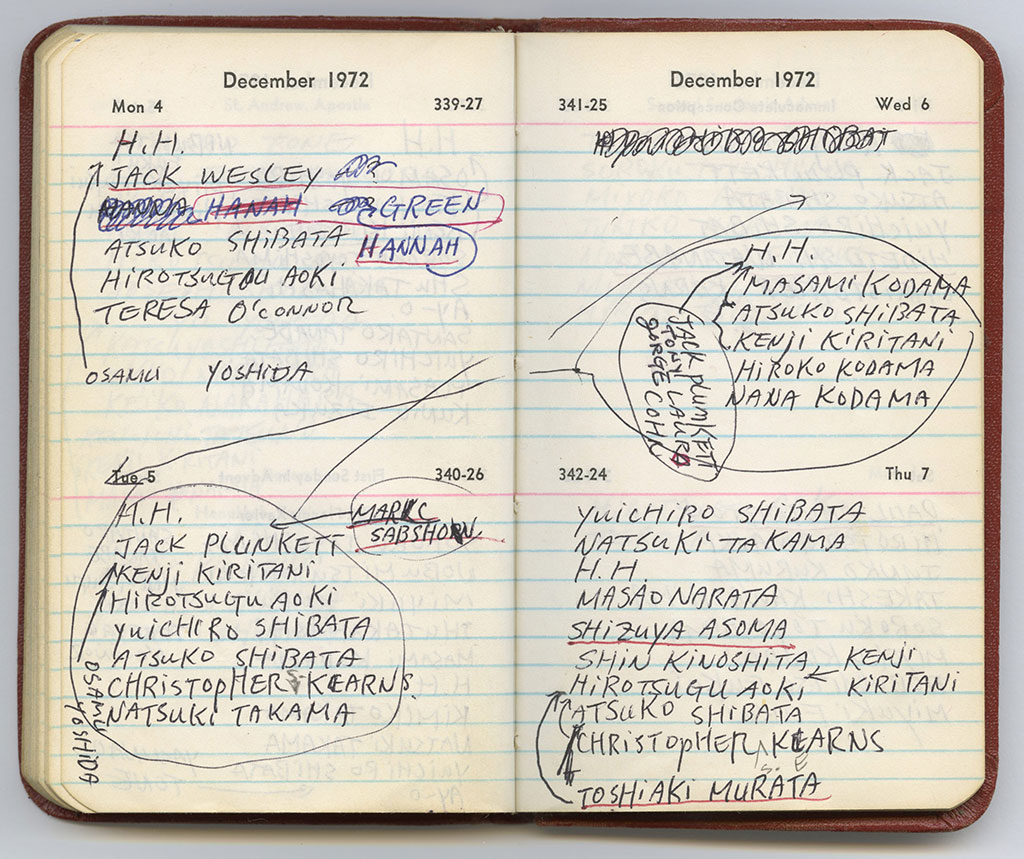

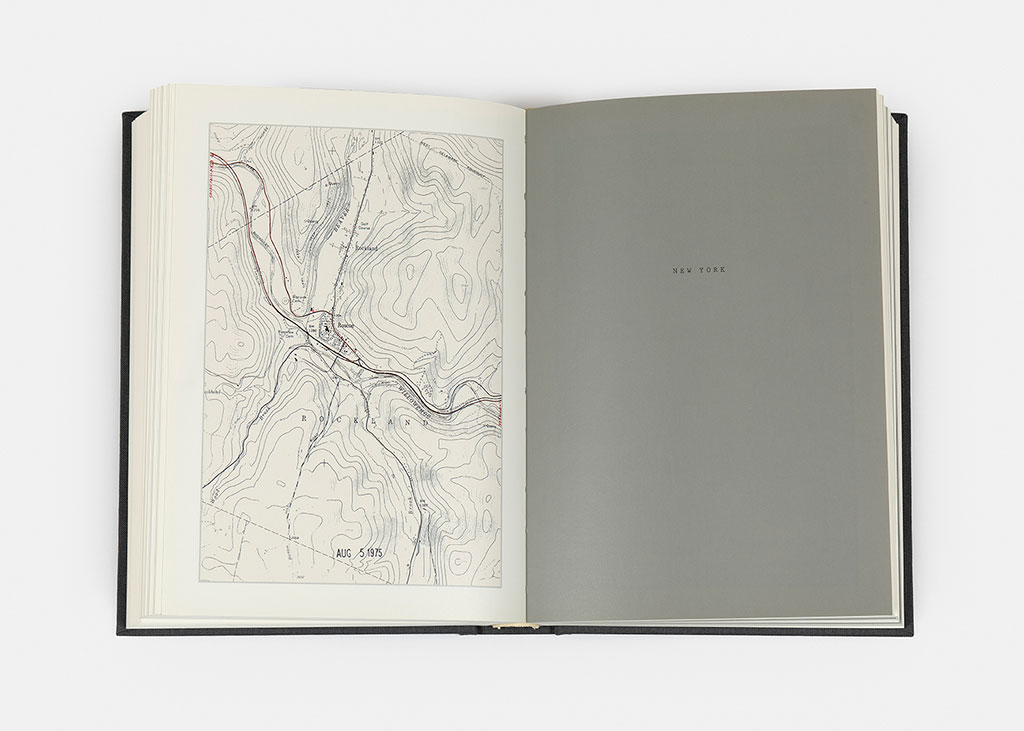

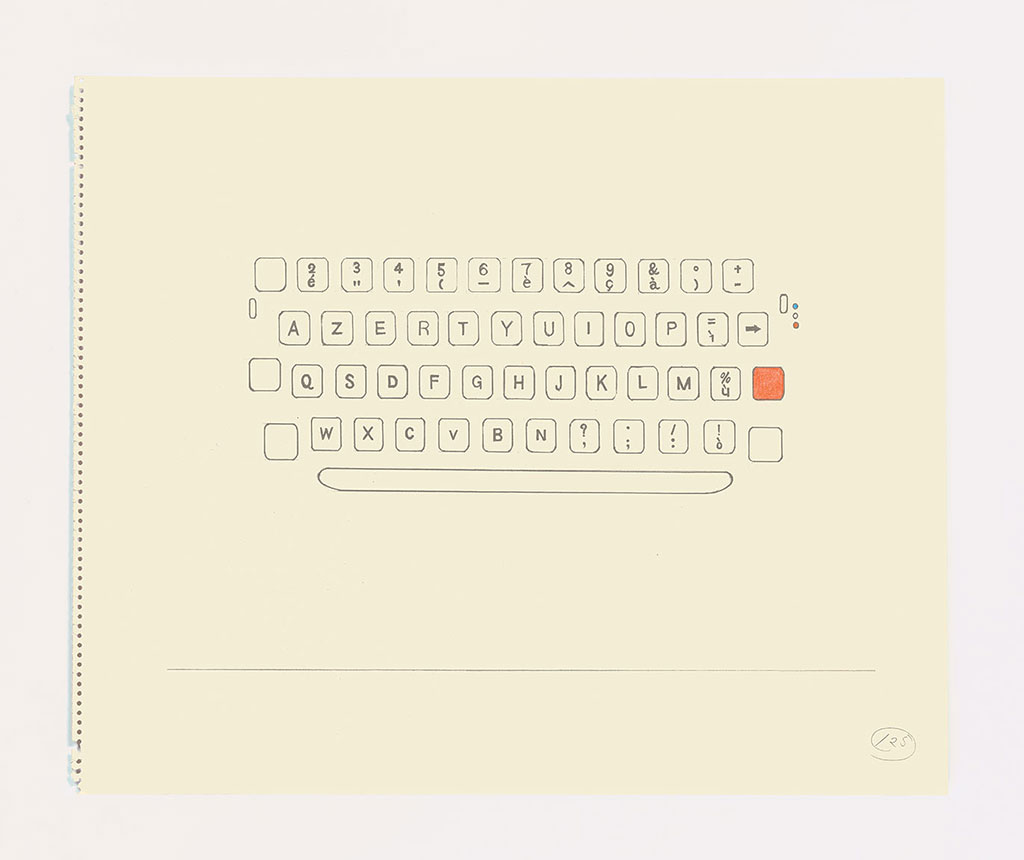

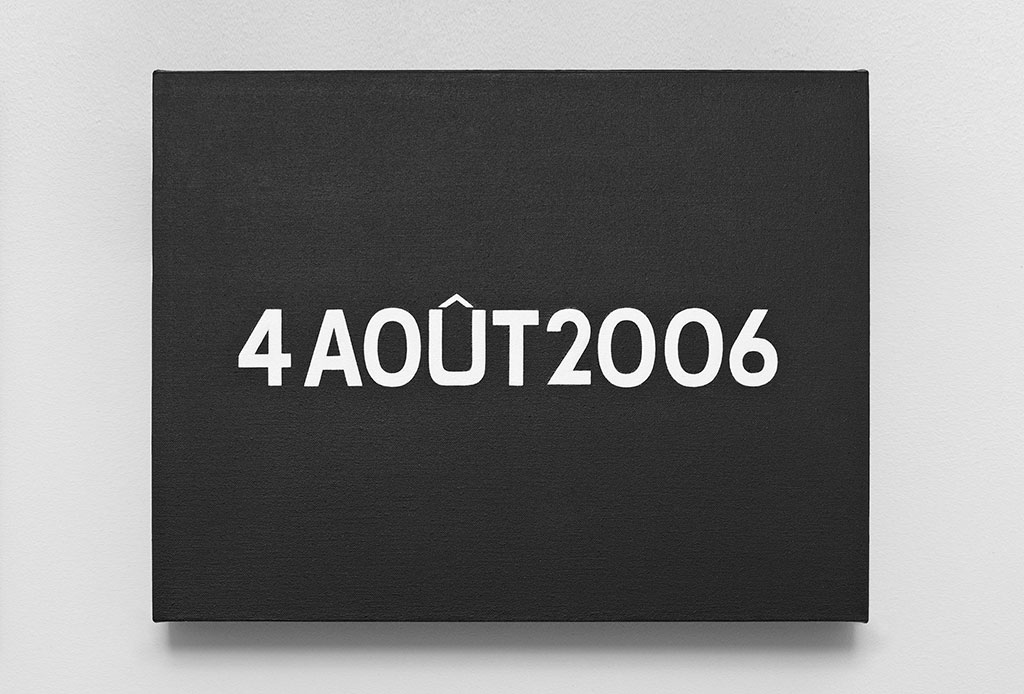

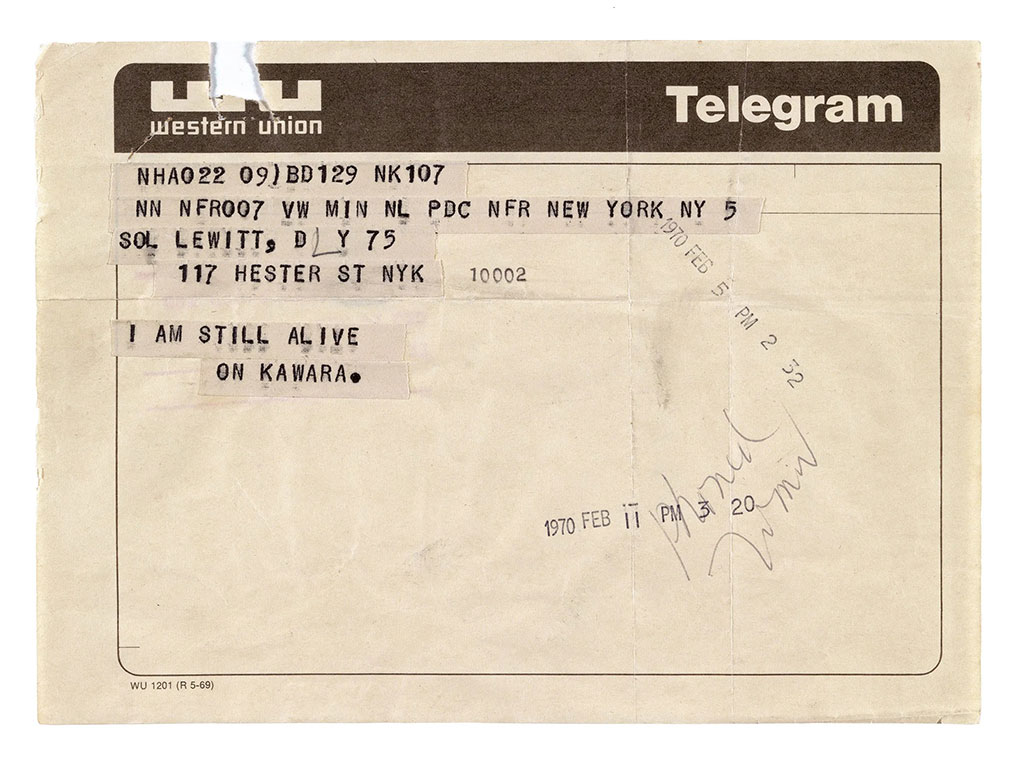

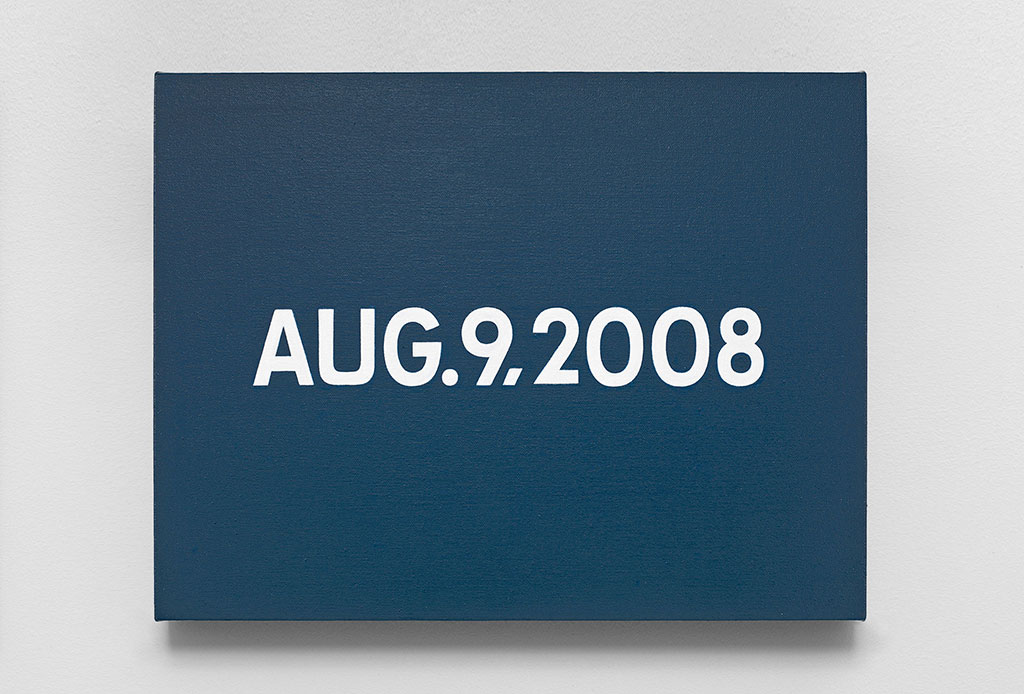

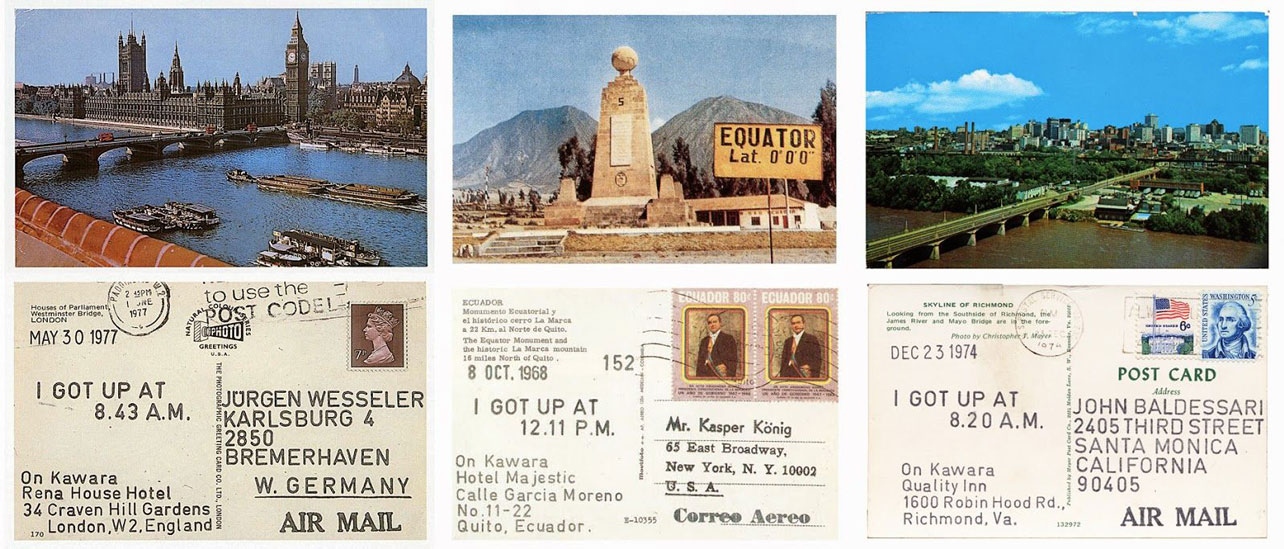

On Kawara was born in 1932, raised in an intellectual family environment informed by aspects of Buddhist, Shinto, and Christian religion. In common with Japanese society as a whole, he was greatly affected by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which occurred when he was a teenager, and which left him deeply unsettled, questioning the moral values underpinning human society. After graduating from high school in 1951, he relocated to Tokyo, where he spent much of his time in bookstores, studying European philosophy and political and psychoanalytic theory. He quickly acquired a reputation within the Japanese avant-garde art scene, attaching himself to the Avant-Garde Art Association established by Kikuji Yamashita and other painters of a broadly leftist, Social Realist persuasion. Kawara’s own 1950s work, such as “Thinking Man”, eschews obvious social commentary for a more elliptical, surrealist style, though still clearly imbued with political content. Just as he was gaining a cult-like following in Tokyo, Kawara became frustrated with the art scene there. In 1959, Kawara moved with his father to Mexico City, where he remained for four years, using it as a base to study modern art and to travel around the country. In Mexico, Kawara later recalled, he first became aware of time as an intrinsic, potentially unpredictable backdrop to human experience: in Japan, everything had run on schedule; in Mexico, schedules, timetables, itineraries, were often inaccurate. For a short period during 1961-62, Kawara attended the art department of Mexico City University. In 1962, Kawara moved from Mexico City to New York, where he remained for eight months before travelling to Paris. From Paris he travelled to Toledo in Spain, making a pilgrimage to view the Altamira cava paintings. In 1964, back in Paris, he began a series of drawings that he continued after returning to New York in the autumn of that year. The “1964 Paris – New York” series abandons the figurative representation of his 1950s work for combinations of obscure diagrams and symbols, sketches of imagined sculptural environments and installations, and brief, obscure, written messages. Many of these techniques are shared in common with Minimalist painting and Conceptual art. Kawara settled in New York in 1964 and began to create the works that would characterize his mature period. Some of his early-to-mid 1960s work contained sequential arrangements of shapes suggestive of a language or code system. Others were monochrome paintings featuring single phrases or words. Although Kawara chose to destroy most of his paintings from this period, these works did convince him of the need to incorporate the written word into his art. By the late 1960s, Kawara had completely abandoned public discussion of his practice. This has made documenting his life and work from that point onwards very difficult, with art historians forced to piece together a biography from the documentary records included in – and produced in conjunction with – Kawara’s work. On 4/1/966, Kawara began the “Today” series, a project which he would continue for almost fifty years. The so-called “Date Paintings” that make up the series consist of square canvases of varying sizes, on which the date of the painting is written in sans serif font, with various compositional features altering depending on the date, and on the artist’s location. The “Today” project also spawned a set of associated, ritualistic practices that became almost as creatively significant as the composition of the paintings themselves. Each painting, for example, was stored in a box lined with newspaper from the day of composition, and annual journals were produced documenting various facts about the composition of the works. Because of the isolation in which Kawara worked from the late 1960s onwards, his biography from that point onwards is, to all intents and purposes, identical with the record of his artistic activity from that point. Bearing this in mind, other significant long-term projects include “I Read” (1966-95), a set of binders of annotated newspaper clippings, with a page added for each day on which a “Date Painting” was made; “I Got Up” (1968-79), a series of picture postcards sent daily, in pairs, to friends, family, and patrons bearing the inscription “I GOT UP AT … “; “I Met” (1968-79), a set of lists, documenting by date everyone whom the artist met over an eleven-year period; and “I Am Still Alive” (1970-2000), a series of telegrams sent at irregular intervals to random recipients, assuring them that the artist was not yet dead. On Kawara died in 2014. In keeping with the spirit of his work, his obituaries noted that he been alive for 29,771 days.

On Kawara was born in 1932, raised in an intellectual family environment informed by aspects of Buddhist, Shinto, and Christian religion. In common with Japanese society as a whole, he was greatly affected by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which occurred when he was a teenager, and which left him deeply unsettled, questioning the moral values underpinning human society. After graduating from high school in 1951, he relocated to Tokyo, where he spent much of his time in bookstores, studying European philosophy and political and psychoanalytic theory. He quickly acquired a reputation within the Japanese avant-garde art scene, attaching himself to the Avant-Garde Art Association established by Kikuji Yamashita and other painters of a broadly leftist, Social Realist persuasion. Kawara’s own 1950s work, such as “Thinking Man”, eschews obvious social commentary for a more elliptical, surrealist style, though still clearly imbued with political content. Just as he was gaining a cult-like following in Tokyo, Kawara became frustrated with the art scene there. In 1959, Kawara moved with his father to Mexico City, where he remained for four years, using it as a base to study modern art and to travel around the country. In Mexico, Kawara later recalled, he first became aware of time as an intrinsic, potentially unpredictable backdrop to human experience: in Japan, everything had run on schedule; in Mexico, schedules, timetables, itineraries, were often inaccurate. For a short period during 1961-62, Kawara attended the art department of Mexico City University. In 1962, Kawara moved from Mexico City to New York, where he remained for eight months before travelling to Paris. From Paris he travelled to Toledo in Spain, making a pilgrimage to view the Altamira cava paintings. In 1964, back in Paris, he began a series of drawings that he continued after returning to New York in the autumn of that year. The “1964 Paris – New York” series abandons the figurative representation of his 1950s work for combinations of obscure diagrams and symbols, sketches of imagined sculptural environments and installations, and brief, obscure, written messages. Many of these techniques are shared in common with Minimalist painting and Conceptual art. Kawara settled in New York in 1964 and began to create the works that would characterize his mature period. Some of his early-to-mid 1960s work contained sequential arrangements of shapes suggestive of a language or code system. Others were monochrome paintings featuring single phrases or words. Although Kawara chose to destroy most of his paintings from this period, these works did convince him of the need to incorporate the written word into his art. By the late 1960s, Kawara had completely abandoned public discussion of his practice. This has made documenting his life and work from that point onwards very difficult, with art historians forced to piece together a biography from the documentary records included in – and produced in conjunction with – Kawara’s work. On 4/1/966, Kawara began the “Today” series, a project which he would continue for almost fifty years. The so-called “Date Paintings” that make up the series consist of square canvases of varying sizes, on which the date of the painting is written in sans serif font, with various compositional features altering depending on the date, and on the artist’s location. The “Today” project also spawned a set of associated, ritualistic practices that became almost as creatively significant as the composition of the paintings themselves. Each painting, for example, was stored in a box lined with newspaper from the day of composition, and annual journals were produced documenting various facts about the composition of the works. Because of the isolation in which Kawara worked from the late 1960s onwards, his biography from that point onwards is, to all intents and purposes, identical with the record of his artistic activity from that point. Bearing this in mind, other significant long-term projects include “I Read” (1966-95), a set of binders of annotated newspaper clippings, with a page added for each day on which a “Date Painting” was made; “I Got Up” (1968-79), a series of picture postcards sent daily, in pairs, to friends, family, and patrons bearing the inscription “I GOT UP AT … “; “I Met” (1968-79), a set of lists, documenting by date everyone whom the artist met over an eleven-year period; and “I Am Still Alive” (1970-2000), a series of telegrams sent at irregular intervals to random recipients, assuring them that the artist was not yet dead. On Kawara died in 2014. In keeping with the spirit of his work, his obituaries noted that he been alive for 29,771 days.