ART CITIES:Vienna-Cybernetics of the Poor

The exhibition “Cybernetics of the Poor” examines the relationship between art and cybernetics and their intersections in the past and present. From the late 1940s on, the term cybernetics began to be used to describe self-regulating systems that measure, anticipate, and react in order to intervene in changing conditions. Initially relevant mostly in the fields of administration, planning, and criminology, and early ecology, under digital capitalism cybernetics has become an economic factor (see: big data). In such a cybernetic totality art must respond to a new situation: as a cybernetics of the poor.

The exhibition “Cybernetics of the Poor” examines the relationship between art and cybernetics and their intersections in the past and present. From the late 1940s on, the term cybernetics began to be used to describe self-regulating systems that measure, anticipate, and react in order to intervene in changing conditions. Initially relevant mostly in the fields of administration, planning, and criminology, and early ecology, under digital capitalism cybernetics has become an economic factor (see: big data). In such a cybernetic totality art must respond to a new situation: as a cybernetics of the poor.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Kunsthalle Wien Archive

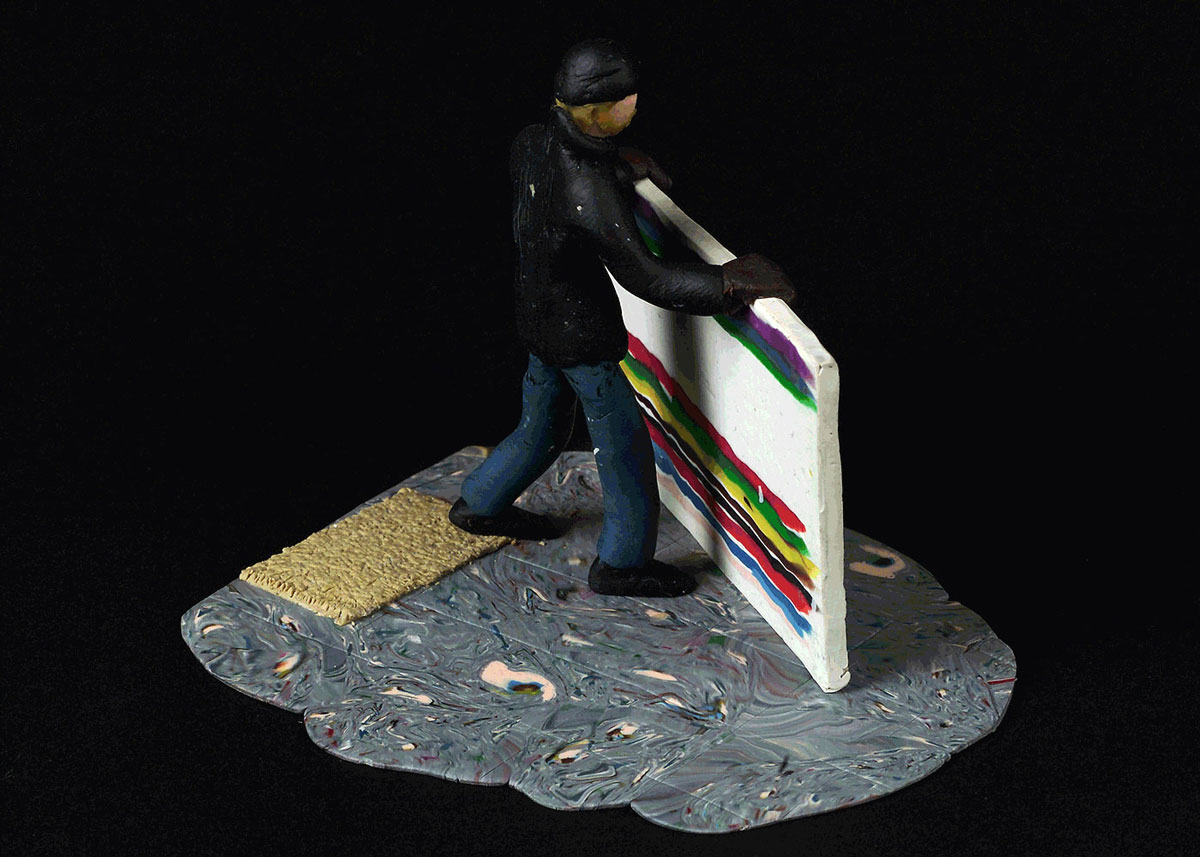

The exhibition “Cybernetics of the Poor” combines historical positions and proposals that respond to the new situation where cybernetics is no longer just a concept of power but also one of profit, with both coming together in the notion of control and anticipation through collected data. Four contemporary artists respond to this situation in various ways and have produced new work for this show. But there are also many classical or lesser known practitioners who had an interest in this, some of them 50 years ago. Camila Sposati works on the border of sculpture and musical instruments, understanding her objects as containers for future use, a use that does not necessarily need to happen in reality but can be defined potentially as a possible (musical) use that is not random, but is also not predetermined, in that way opposing the culture of pre-sets and apps. She also invokes a post- and anticolonial perspective: where does contemporary cyberculture proceed from, how did it reach the non-Western world? Lili Reynaud-Dewar addresses the architectural and institutional logic of museums and other sites of contemporary culture. This French artist, with a history in performance art, film, literature and especially the history of Queer and Afro-Diasporic themes, dances around and inside buildings, transgressing their functional limits. The way the building anticipates and cybernetically regulates gazes, views and movements is countered not with an anarchist gesture but with a language of dance moves and the alien intrusion of a naked, painted, female body moving in a very specific way, exercising an anti-plan by using well defined elements of the dance lexicon without score, drama or an audience. The dances are filmed and edited. In “29 Conditions for a Self-Imposition”, Jon Mikel Euba explores the ways in which language structures the body. For a number of years, as an extension to his sculptural work, Euba has also been writing. In his practice, thinking about exercise is to think about the ways in which language and body determine each other through a kind of mutual contagion. With this piece, produced specifically in the context of the exhibition, Jon Mikel Euba goes one step further by focusing on the construction of a work system and once again puts the emphasis on the activity itself, on the use of language, rather than on the result. Agency is an artistic initiative based in Brussels whose work involves analysing the legal framework within which artists work. In this way, it provides a response to the cyber capitalist regime in the very place where the basic concepts of intellectual and creative property are defined. Within the framework of this exhibition, the ambitious proposal is to revisit a total of more than 100 cases of collective activity classified in its archive. Those related to the fan phenomenon are among the most outstanding. The work represents the redefinition of the creative subject as an agent intersected by all kinds of anonymous and impersonal authorities. The exhibition also shows other contemporary artists who regularly react in one way or another to the challenge of cybernetic control and economy. Constanze Ruhm has made several feature films that are based on the continuation of the life stories of female fictional characters. The many parts of this series of films finally arrive at the question of death and the possibility of burial, a final death of the programmatic potentiality of the and are ideological and programmatic abstractions in a human form: the raw material of cyber capitalism. Ana de Almeida and Alicja Rogalska from Portugal and Poland have been working for a while on role plays, feminist versions of so called LARPs, Live-Action-Role Plays. They will do a version of the game during the show and also present the results within the exhibition.

Some artists are represented by scores and/or work based on scores. The score represents a social programme that has to deal with the dialectics of control and openness, and does so in an exemplary way that is different from the dominant use of such anticipation of human reactions. Cornelius Cardew with his collective The Scratch Orchestra, after experimenting with aleatoric and graphic notation, tried to directly connect utopian politics with musical practice. Luke Fowler has produced a retrospective essay on this attempt with his film “Pilgrimage from Scattered Points” (2016). Anthony Braxton, maybe the richest and most wide-reaching innovator of Jazz in the last 50 years, has also tried to notate his musical pieces, performances and operas in different ways, trying to be precise and open at the same time. Alex Mendizabal also highlights the ability of elements such as sheet music to question the authority granted to an institution such as the orchestra. For orchestra is the result of an obsessive exercise which began with the simple aim of producing a quantity of compositions per day. While Famoseca proposes a composition for a carousel in motion. A path which years later the artist would continue to explore through the “Curva Chiusa” project. Don Van Vliet, better known by his stage name Captain Beefheart, did not write scores, but often explained that his turn from music to painting was not a silencing; he understood his paintings to be “very loud”, as a visual statement of an interpretation, a reading that should be heard. Noa Eshkol was a dancer and dance instructor who was deeply interested in cybernetics and a good friend of Heinz von Foerster, who introduced her to NASA. The space programmes were able use her knowledge of dance and body movements and her unique notation method. Sharon Lockhart, who was also important for the rediscovery of Eshkol, has photographed the three-dimensional, “sculptural” notation system of Eshkol. The piece “Scale” by Elena Asins also arises from the artist’s inexhaustible interest in all kinds of notation systems and their application to the plastic arts as a way of restricting the quality of the personal to the minimum. The notion of a computational art, referred to by Asins at different times, demonstrates a radical questioning of the separation between mechanical and sensitive exercise. Jorge Oteiza, a sculptor and artist who is known, among other things, for his unfinished projects, makes a foray into musical composition through scores created out loud with his own voice, proposing a first rehearsal without an orchestra in which the artist reveals himself to be a great ventriloquist capable of occupying and interchanging different positions and sound registers. The discovery of programmes and scores in nature has often been taken up by cybernetic ideology and metaphorology. The human genome project seems to provide a legitimation of a programmed world via nature and its code writing. The Austrian artist Jörg Schlick used the beginning of the Human Genome Code after it had been documented by a German newspaper (filling their entire cultural section and applied it in the organization of photographs. He used the code as an organizational tutorial by applying it to something completely different, demonstrating the randomness but also the beauty of organizational systems and their potentials.

Hanne Darboven has done something similar in her life work of writings and drawings that follow strict organizational systems which function for her like self-ordered laws or rules, replacing social control not by its opposite, but by a different, self-developed set of rules. These kinds of projects often grew out of conceptual practices. Darboven was always known for her seriousness, although we are showing a work that plays humorously with the controlled life of school children. Less serious on a superficial level, but very philosophical, are the projects by Douglas Huebler, among them a series of photographs showing every human being on earth. Incomplete of course, like Schlick’s project to organize photographs according to the human genome, whatever its length, but perfectly illustrating and illuminating the concept of a cybernetics of the poor. This is a hopeless, philosophically honest, tragically funny attempt by a human to behave like a God, or a machine, or a cyber capitalist data collection for profit—and of course failing. Similarly the photographer Heinrich Riebesehl who had no background in conceptual art, took a series of photographs in an elevator of the publishing house he worked for in the German city of Hannover in the 1960s. He portrayed people as if he was a surveillance camera—long before such a thing came into existence. The work “The Rescue of the Ear and the Moustache” (2016) by Gema Intxausti also refers to control and surveillance techniques. Although in this case the action takes the form of an exploration of the Stasi Museum in Berlin. The drawings she creates based on the surveillance systems of the former GDR may well be the result of a delirium of the senses, but they are consistent with the detailed observation of different documentary sources collected by the artist. The locus of many of the artists in this exhibition is situated between a score and an exercise. Peter Roehr, an artist who worked in advertising for most of his short adult life, tried to capture the monotony and minimalist charm of the controlled life in a consumer society. He left behind several hundred works in which he exclusively pursued the idea of serial repetition. Pedro G. Romero, meanwhile, entrusts flamenco dancer Israel Galván with the mission of showing us the space within a dwelling. The work of Mike Kelley is characterised, inter alia, by exploring the psychopathological dimension of cyber capitalism in a singular way through the manipulation of the most common objects. The two-channel video in this exhibition documents an installation with a markedly theatrical character, in which visitors to an exhibition by the artist are invited to interact with objects displayed in an enclosed space. Kelley, and the Los Angeles performance scene in general, has been considerably influenced by the work of Guy de Cointet, which reflects a profound interest in the forms of theatricality that are rehearsed within art based on an elaborate textual and objectual production. His investigations and games with language, the use of humour and his ability to move between different media have made Guy de Cointet a point of reference for different generations of artists, as well as one of the benchmarks for the practice of performance. In summary, the exhibition is made up of a constellation of works in which artists make use of various tactics to challenge but at the same time learn from the prevailing cybernetic order; strategies and methodologies that can be understood and defined as characteristic of a cybernetics of the poor.

Photo: Ana de Almeida, Alicja Rogalska & Vanja Smiljanić, NOVA, 2020, production still, © the artists & Kunsthalle Wien, 2020

Info: Curators: Diedrich Diederichsen and Oier Etxeberria, Kunsthalle Wien, Museumsplatz 1, Vienna, Duration: 18/12/2020-28/3/2021, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 11:00-19:00, https://kunsthallewien.at