TRACES: Kiki Smith

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Kiki Smith (18/1/1954- ), who has been known since the 1980s for her multidisciplinary practice relating to the human condition and the natural world. She uses a broad variety of materials to continuously expand and evolve a body of work that includes sculpture, printmaking, photography, drawing, and textiles.Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history.

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Kiki Smith (18/1/1954- ), who has been known since the 1980s for her multidisciplinary practice relating to the human condition and the natural world. She uses a broad variety of materials to continuously expand and evolve a body of work that includes sculpture, printmaking, photography, drawing, and textiles.Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history.

By Dimitris Lempesis

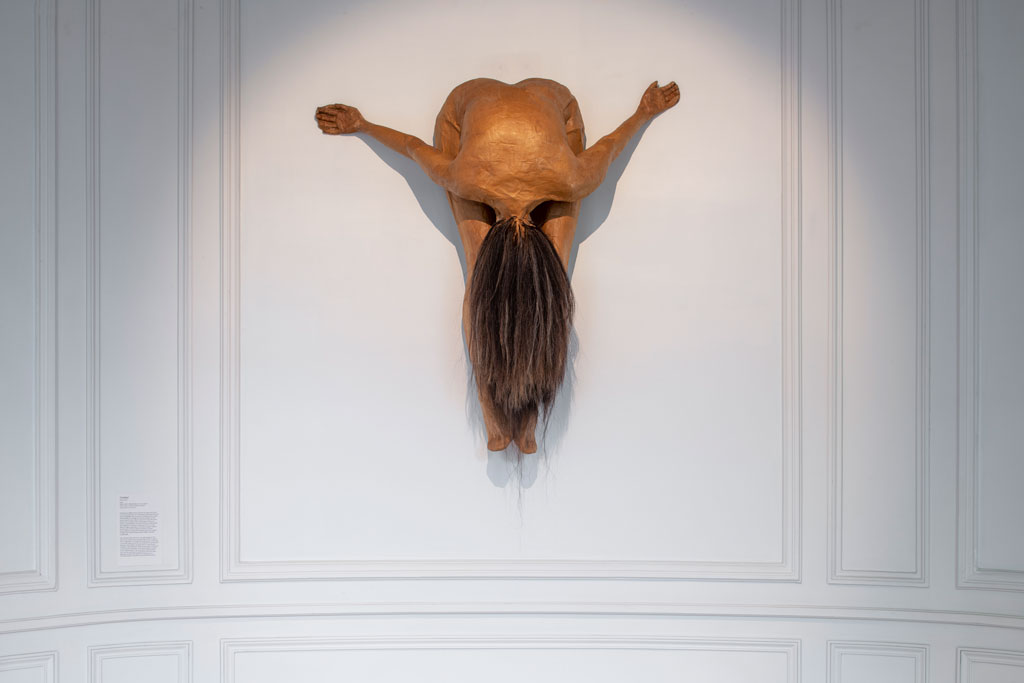

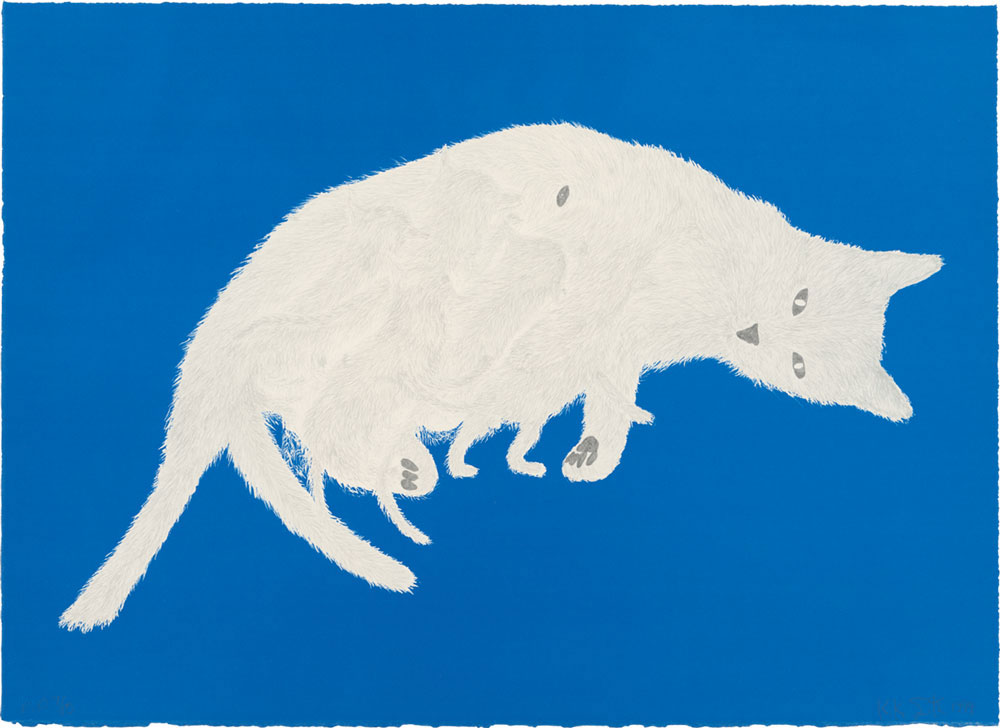

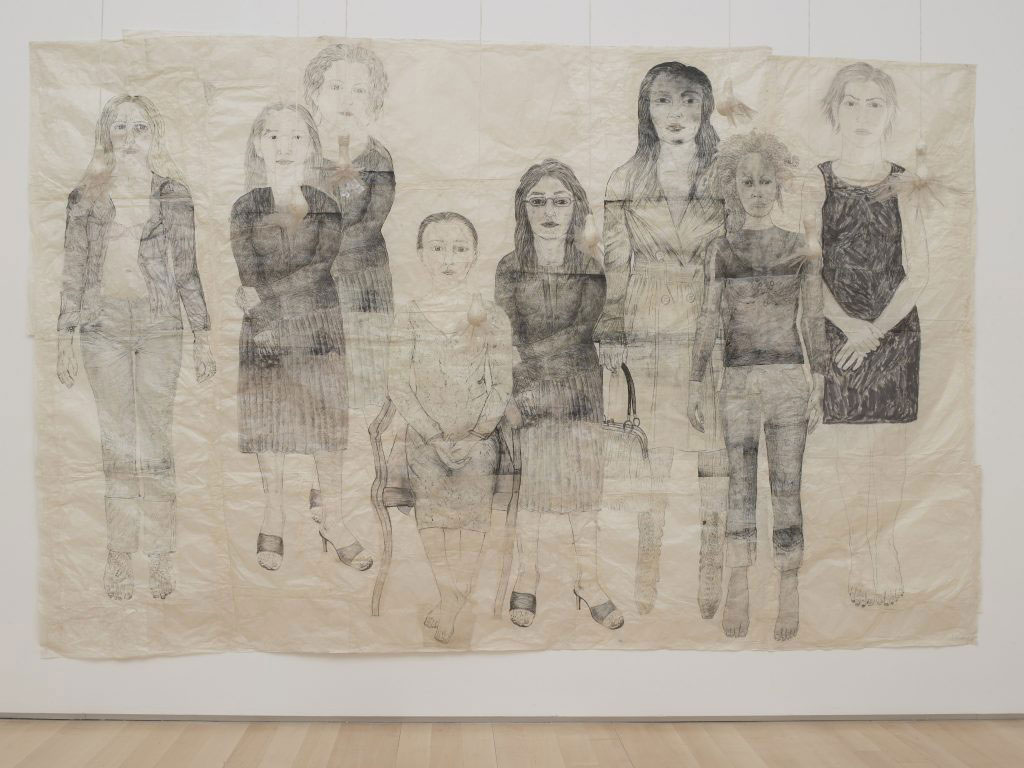

Kiki Smith was born in Nuremberg, Germany, the daughter of sculptor Tony Smith. Brought up in South Orange, New Jersey, she enrolled at Hartford Art School in Connecticut in 1974 but dropped out 18 months later. Settling in New York in 1976, Smith earned her living over the next few years doing odd jobs. Around 1978, she joined Collaborative Projects, Inc. (Colab), an artists’ collective devoted to making art accessible through exhibitions outside commercial gallery settings. It was during this period that she made her first artworks, monotypes of everyday objects. Virtually self-taught, Smith describes herself as “a thing-maker”. With the death of her father in 1980, Smith turned her attention to themes of mortality and decay, focusing on human corporeality. “Hand in Jar” (1983) consists of a latex hand covered in algae and submerged in a mason jar filled with water. Its clinical realism calls to mind a pathology lab or a dissecting studio. In 1985, propelled by an interest in obtaining practical knowledge about the body, Smith studied to become an emergency medical technician. The impact of this experience on her work was immediate and profound. “Possession Is Nine-Tenths of the Law” (1985) is a series of nine screenprints and monotypes of deadpan views of various internal organs. Its legalistic title alludes to the artist’s nascent feminist concerns regarding the body, particularly the female body, as a battleground for social and political ideologies. Smith offered similarly clinical treatments of human organs in her sculptures of the period, including “Glass Stomach” (1985), “Untitled (Heart)” (1986), and “Second Choice” (1987), a bowl of castoff lungs, liver, heart, and spleen. Smith’s interest in the human body led to a related cycle of works devoted to bodily fluids, a particularly poignant subject during the AIDS crisis. “Game Time” (1986) consists of twelve blood-filled glass jars stacked on a shelf on which has been stamped “There are approx. 12 pints of blood in the human body”. “Untitled” (1986) comprises twelve empty glass water-cooler jugs with the names of twelve different secretions generated by the body (pus, vomit, saliva, urine, semen, and so on) engraved on them in Gothic script. In the mid-1980s, as abortion came to the political fore, Smith began a series of works devoted to reproduction and birth. A pair of bronze sculptures represents the male and female urogenital systems “(Uro-Genital System (Male)” and “Uro-Genital System (Female)” both 1986. “Womb” (1986) is a swollen uterus cast in bronze and hinged on one side; when opened, it reveals its emptiness, a metaphor for women’s struggle to control their bodies. “Untitled” (1988–90) is comprised of more than two hundred handmade lead-crystal sperm whose dazzling beauty and delicacy suggest the miracle of human generation but also belie the perilous power of semen to transmit disease. Smith’s frank investigation of the body continued in the early 1990s, when she adopted the life-size human figure as her subject. “Untitled” (1990) shows a male and female in beeswax, dangling lifeless from supports, as if crucified. The red blotches on their skin bespeak physical trauma. Milk drips from the woman’s breasts and semen streams down the man’s leg. These violated, sacrificial bodies not only evoke the Catholicism of Smith’s upbringing but also recall other artworks, from Hans Grünewald’s “Isenheim Altarpiece” (1512-14) to Jasper Johns’s early paintings with cast limbs. Smith’s most unsettling sculptures address the alliance between femininity and abjection. “Pee Body” (1992) depicts a nude female figure in wax, crouched on the floor relieving herself, urine trailing behind in the form of yellow beads. A gush of red beads streams from the vagina of the standing nude in “Train” (1993), while “Tail” (1992) presents a similar personage on all fours with a long trail of excrement extending from her anus. Smith sustains equally honest, jarring representations of femininity in works devoted to Little Red Riding Hood, Eve, Mary Magdalene, and the Virgin Mary. She then shifted focus to the animal kingdom, especially birds, whose ferocity and vulnerability echo the human condition. “Jersey Crows” (1995) comprises more than a dozen dead crows cast in bronze, strewn across the gallery floor, Smith’s homage to these victims of pesticide poisoning in her home state. “Rapture” (2002), an etching, aquatint, and drypoint, portrays a female nude, which resembles the artist, being mauled by a lion. Smith’s recent work draws directly from her long-standing interest in dolls and marionettes; the seemingly naive, homespun aesthetic of her sculptures of “Io” (2005) and “Miss May” (2007) allude to the innocence, violence, and anxiety of fairytales. In 2019 Kiki Smith presented “Memory”, a site-specific exhibition at DESTE Foundation’s Project Space at the Slaughterhouse on Hydra island, Greece. Her latest Museum exhibition is at Monnaie de Paris (18/10/19-9/2/20), brings together almost one hundred works from the 1980s to the present day. Visitors are greeted by two sculptures in the exterior courtyards of Monnaie de Paris and the exhibition itself is held on two floors, covering more than 1000m2. The exhibition covers the major themes of her oeuvre.

Kiki Smith was born in Nuremberg, Germany, the daughter of sculptor Tony Smith. Brought up in South Orange, New Jersey, she enrolled at Hartford Art School in Connecticut in 1974 but dropped out 18 months later. Settling in New York in 1976, Smith earned her living over the next few years doing odd jobs. Around 1978, she joined Collaborative Projects, Inc. (Colab), an artists’ collective devoted to making art accessible through exhibitions outside commercial gallery settings. It was during this period that she made her first artworks, monotypes of everyday objects. Virtually self-taught, Smith describes herself as “a thing-maker”. With the death of her father in 1980, Smith turned her attention to themes of mortality and decay, focusing on human corporeality. “Hand in Jar” (1983) consists of a latex hand covered in algae and submerged in a mason jar filled with water. Its clinical realism calls to mind a pathology lab or a dissecting studio. In 1985, propelled by an interest in obtaining practical knowledge about the body, Smith studied to become an emergency medical technician. The impact of this experience on her work was immediate and profound. “Possession Is Nine-Tenths of the Law” (1985) is a series of nine screenprints and monotypes of deadpan views of various internal organs. Its legalistic title alludes to the artist’s nascent feminist concerns regarding the body, particularly the female body, as a battleground for social and political ideologies. Smith offered similarly clinical treatments of human organs in her sculptures of the period, including “Glass Stomach” (1985), “Untitled (Heart)” (1986), and “Second Choice” (1987), a bowl of castoff lungs, liver, heart, and spleen. Smith’s interest in the human body led to a related cycle of works devoted to bodily fluids, a particularly poignant subject during the AIDS crisis. “Game Time” (1986) consists of twelve blood-filled glass jars stacked on a shelf on which has been stamped “There are approx. 12 pints of blood in the human body”. “Untitled” (1986) comprises twelve empty glass water-cooler jugs with the names of twelve different secretions generated by the body (pus, vomit, saliva, urine, semen, and so on) engraved on them in Gothic script. In the mid-1980s, as abortion came to the political fore, Smith began a series of works devoted to reproduction and birth. A pair of bronze sculptures represents the male and female urogenital systems “(Uro-Genital System (Male)” and “Uro-Genital System (Female)” both 1986. “Womb” (1986) is a swollen uterus cast in bronze and hinged on one side; when opened, it reveals its emptiness, a metaphor for women’s struggle to control their bodies. “Untitled” (1988–90) is comprised of more than two hundred handmade lead-crystal sperm whose dazzling beauty and delicacy suggest the miracle of human generation but also belie the perilous power of semen to transmit disease. Smith’s frank investigation of the body continued in the early 1990s, when she adopted the life-size human figure as her subject. “Untitled” (1990) shows a male and female in beeswax, dangling lifeless from supports, as if crucified. The red blotches on their skin bespeak physical trauma. Milk drips from the woman’s breasts and semen streams down the man’s leg. These violated, sacrificial bodies not only evoke the Catholicism of Smith’s upbringing but also recall other artworks, from Hans Grünewald’s “Isenheim Altarpiece” (1512-14) to Jasper Johns’s early paintings with cast limbs. Smith’s most unsettling sculptures address the alliance between femininity and abjection. “Pee Body” (1992) depicts a nude female figure in wax, crouched on the floor relieving herself, urine trailing behind in the form of yellow beads. A gush of red beads streams from the vagina of the standing nude in “Train” (1993), while “Tail” (1992) presents a similar personage on all fours with a long trail of excrement extending from her anus. Smith sustains equally honest, jarring representations of femininity in works devoted to Little Red Riding Hood, Eve, Mary Magdalene, and the Virgin Mary. She then shifted focus to the animal kingdom, especially birds, whose ferocity and vulnerability echo the human condition. “Jersey Crows” (1995) comprises more than a dozen dead crows cast in bronze, strewn across the gallery floor, Smith’s homage to these victims of pesticide poisoning in her home state. “Rapture” (2002), an etching, aquatint, and drypoint, portrays a female nude, which resembles the artist, being mauled by a lion. Smith’s recent work draws directly from her long-standing interest in dolls and marionettes; the seemingly naive, homespun aesthetic of her sculptures of “Io” (2005) and “Miss May” (2007) allude to the innocence, violence, and anxiety of fairytales. In 2019 Kiki Smith presented “Memory”, a site-specific exhibition at DESTE Foundation’s Project Space at the Slaughterhouse on Hydra island, Greece. Her latest Museum exhibition is at Monnaie de Paris (18/10/19-9/2/20), brings together almost one hundred works from the 1980s to the present day. Visitors are greeted by two sculptures in the exterior courtyards of Monnaie de Paris and the exhibition itself is held on two floors, covering more than 1000m2. The exhibition covers the major themes of her oeuvre.