ART-PRESENTATION: Man Ray,Les Mystères du Château du Dé

Man Ray was the only American to play a major role in both the Dada and Surrealist movements. His work spanned painting, sculpture, film, prints and poetry, he also successfully navigated the worlds of commercial and fine art, and came to be a sought-after fashion photographer. He is perhaps most remembered for his photographs of the inter-war years, in particular the camera-less pictures he called “Rayographs”, but he always regarded himself first and foremost as a painter.

Man Ray was the only American to play a major role in both the Dada and Surrealist movements. His work spanned painting, sculpture, film, prints and poetry, he also successfully navigated the worlds of commercial and fine art, and came to be a sought-after fashion photographer. He is perhaps most remembered for his photographs of the inter-war years, in particular the camera-less pictures he called “Rayographs”, but he always regarded himself first and foremost as a painter.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Gagosian Archive

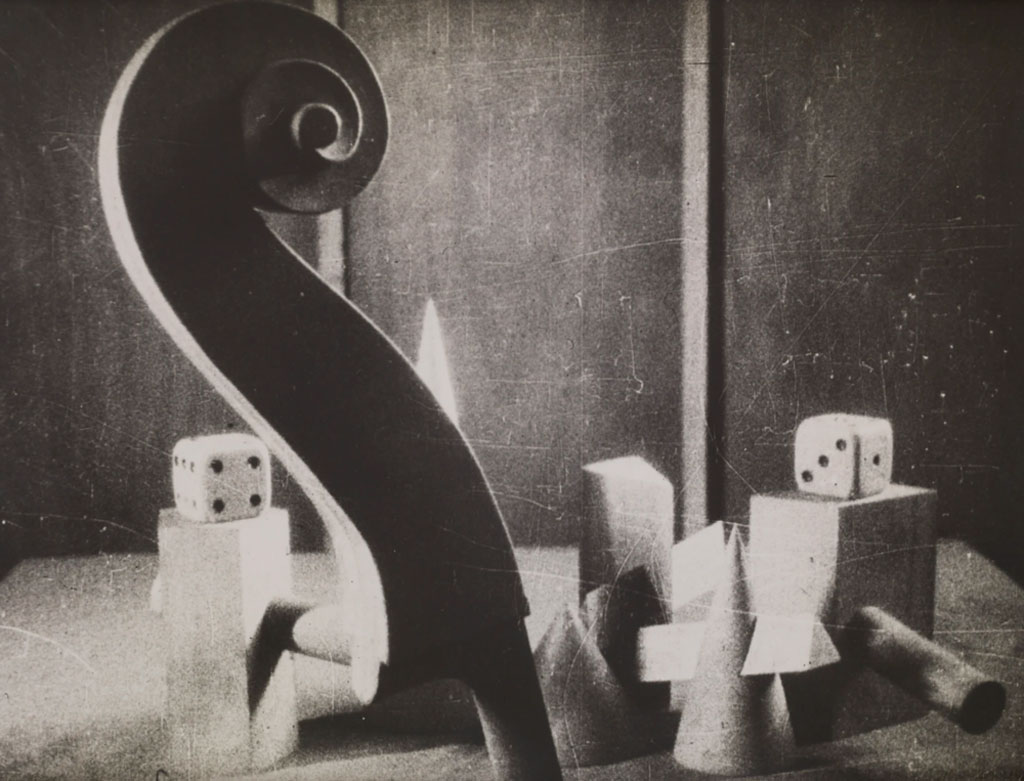

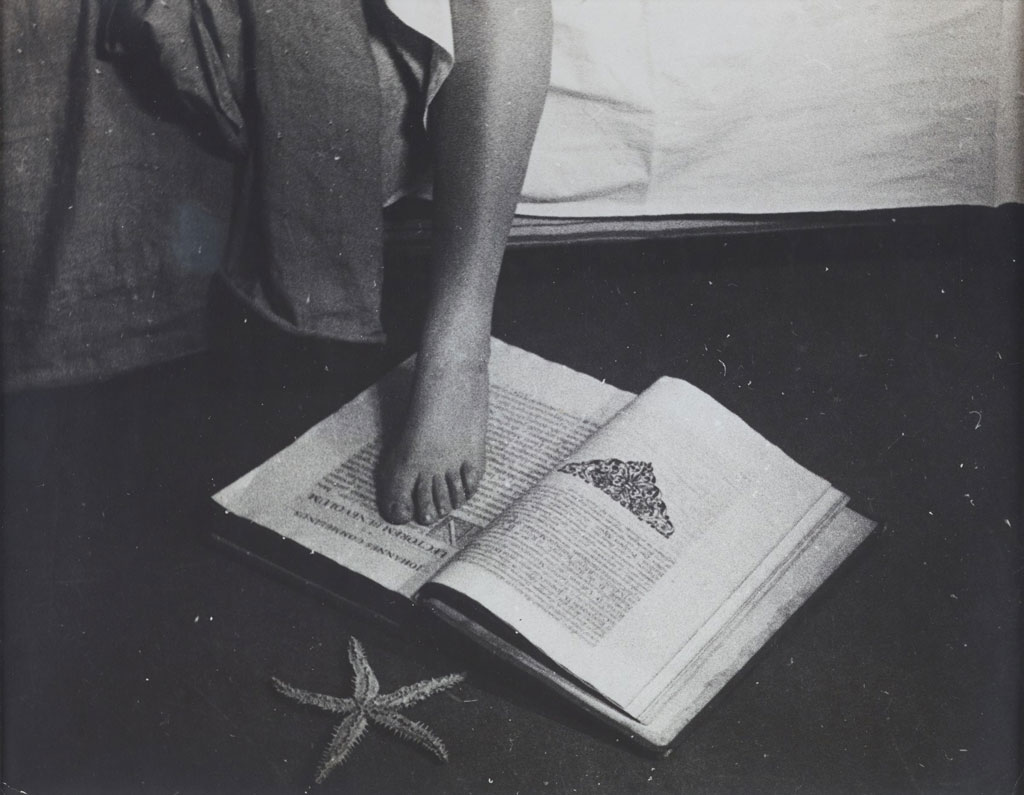

An exhibition with films by the Man Ray entitled “The Mysteries of Château du Dé” is on show at Gagosian Gallery in San Francisco. The films are: “Emak Bakia” (1926), “L ’étoile de mer“ (1928) and “Les Mystères du Château du Dé” (1929) which was not intended for public screening. Man Ray’s first experience in making film was in New York, in , when he worked with Marcel Duchamp on an unsuccessful attempt to create a three-dimensional film. It was when Ray moved to Paris in 1920, that he truly began his career as a photographer and filmmaker. He lived in the artists’s quarter of Montparnasse, and soon fell in love with the famous model, singer, budding actress and well-known Bohemian Kiki de Montparnasse (aka Alice Prin). Kiki became Man Ray’s lover and muse, who he began to photograph, which in turn led him to his first experiment as filmmaker “Le Retour à la Raison” in 1923. Man Ray aligned himself with the Cinéma pur movement, which focused on taking film away from narrative and plot and returning it to movement and image. Its proponents were René Clair, Fernand Léger, Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling, amongst others, and their short films were the beginnings of what is now described as “Art Cinema”. Adhering to Cinéma pur‘s loose manifesto, Man Ray’s early films, “Le Retour à la Raison” in 1923 focused on creating startling textural patterns through the representation of objects within rhythmical loops. The experimental techniques of “Le Retour à la Raison” was repeated and developed in “Emak-Bakia”. Many of the techniques Man Ray developed (double exposure, Rayographs and soft focus) were later co-opted by animators and filmmakers during the 1940s to 1960s. “Emak-Bakia” shows elements of fluid mechanical motion in parts, rotating artifacts showing his ideas of everyday objects being extended and rendered useless. Kiki de Montparnasse is shown driving a car in a scene through a town. Towards the middle of the film Jacques Rigaut appears dressed in female clothing and make-up. Later in the film a caption appears: “La raison de cette extravagance” (the reason for this extravagance). The film then cuts to a car arriving and a passenger leaving with briefcase entering a building, opening the case revealing men’s shirt collars which he proceeds to tear in half. The collars are then used as a focus for the film, rotating through double exposures. “L’Étoile de mer” (1928) is based on a short poem and longer scenario, both written by Robert Desnos. The film depicts a couple (played by Kiki de Montparnasse and André de la Rivière) acting through scenes that are shot out of focus, and with Desnos himself as the second man in the final scene. A character picks up a woman who is selling newspapers. She undresses for him, but then he seems to leave her. Less interested in her than in the weight she uses to keep her newspapers from blowing away, the man lovingly explores the perceptions generated by her paperweight, a starfish in a glass tube. As the man looks at the starfish, we become aware through his gaze of metaphors for cinema, and for vision itself, in lyrical shots of distorted perception that imply hallucinatory, almost masturbatory sexuality. In 1929, Ray started work on his longest film “Les Mystères du Château de Dé”. This time Ray presented the story of two young travelers who visit the Villa Noailles in Hyères, the home of husband and wife Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, the patrons of Picasso, Cocteau, Dali, and many of the Surrealists, with its Cubist garden designed by Gabriel Geuvrikain. The film is surreal, dreamlike, and relies more on atmosphere and suggestion than any real narrative form. In large part it was “inspired by the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé” in particular, his poem “Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira Le Hasard” written in 1897. This poem was published over twenty pages in various typeface and structure. It contained early examples of Concrete Poetry, free verse and presented highly innovative graphic design that would later influence Dada. Some Surrealists criticized Ray’s films for not having enough narrative but Ray was more interested in creating something that didn’t relate to what had gone before. In the same way, he never acknowledged his own history before he became Man Ray. In addition to these three key films, the exhibition also includes objects, drawings, and photography. Moving fluidly between media, Man Ray often made several iterations of a work (photographing it, assembling and disassembling, or making multiples) reproduction being crucial to his concept of the art object.

Photo: Man Ray, L ’étoile de mer (Filmstill), 1928, Gelatin silver print, 23 x 30 cm, © Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society-New York/ADAGP-Paris 2019

Info: Gagosian Gallery, 657 Howard Street, San Francisco, Duration: 14/1-29/2/20, Days & Hours: Mon-Sat 10:00-18:00, https://gagosian.com