TRACES: Mike Kelley

Today is the occasion to bear in mind one of the most influential American artists of the past quarter century and a pungent commentator on American class, popular culture and youthful rebellion Mike Kelley (27/10/1954-31/12/2012). This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind one of the most influential American artists of the past quarter century and a pungent commentator on American class, popular culture and youthful rebellion Mike Kelley (27/10/1954-31/12/2012). This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

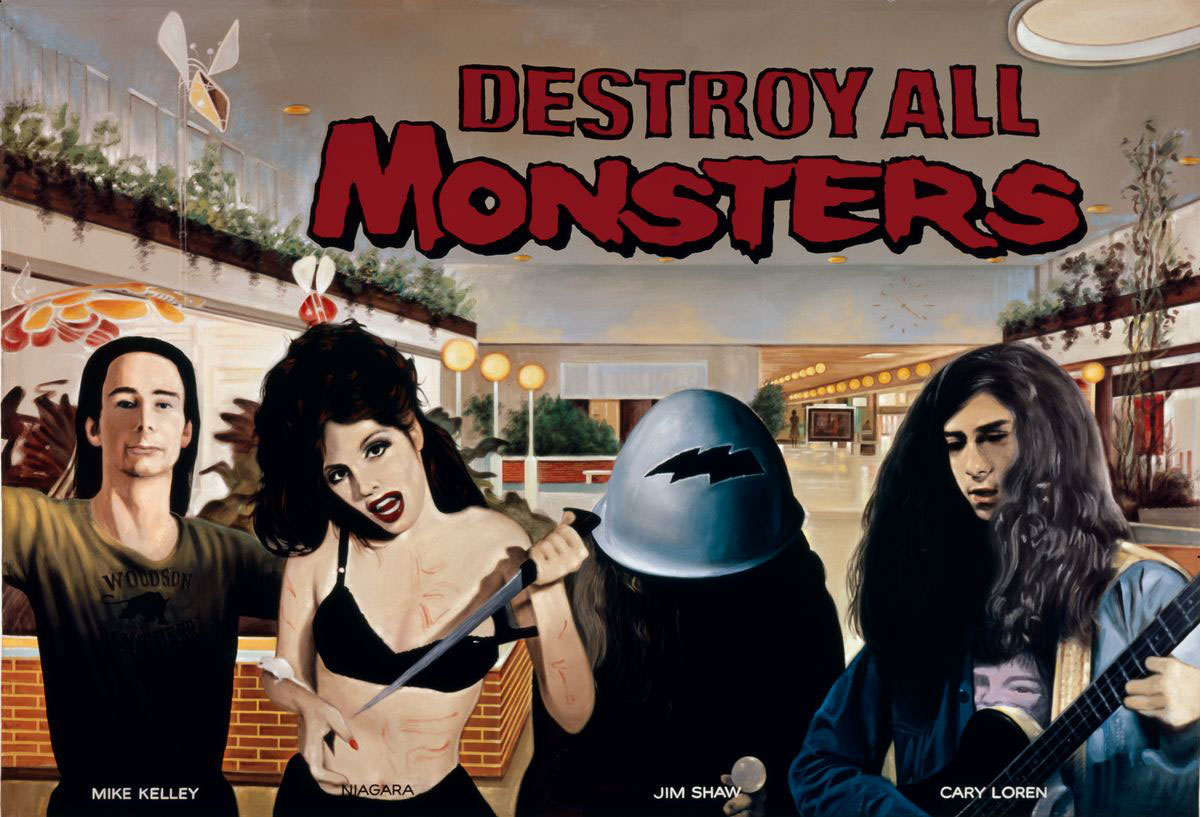

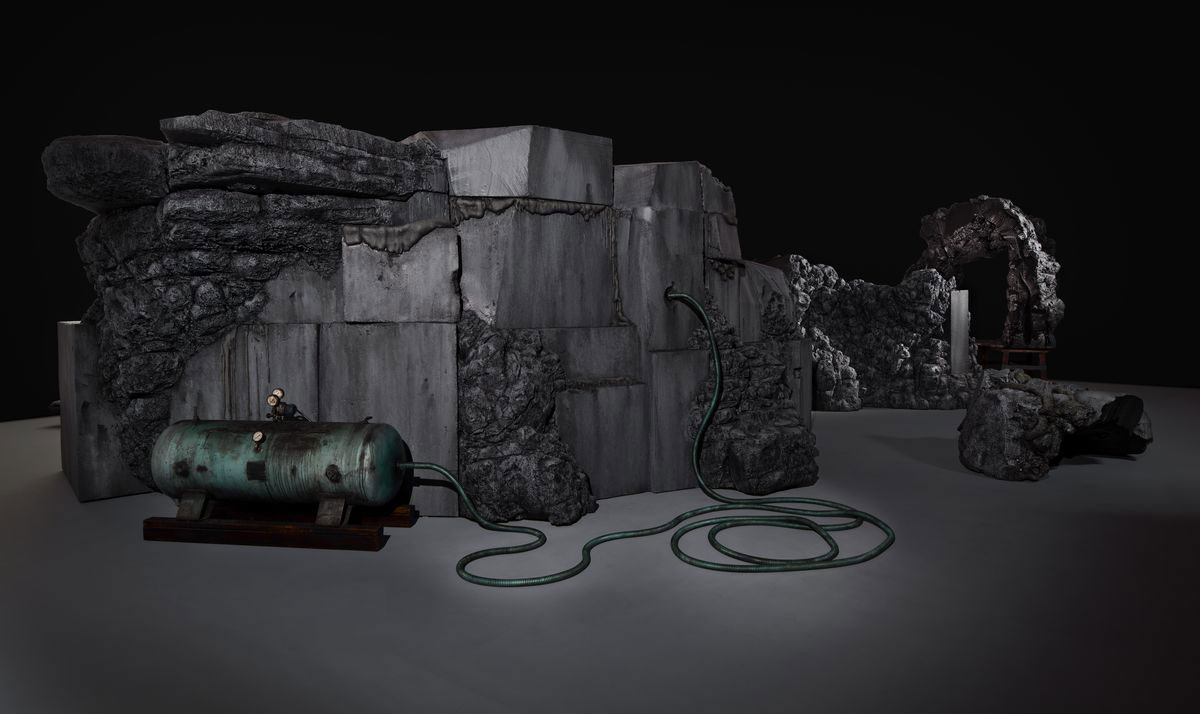

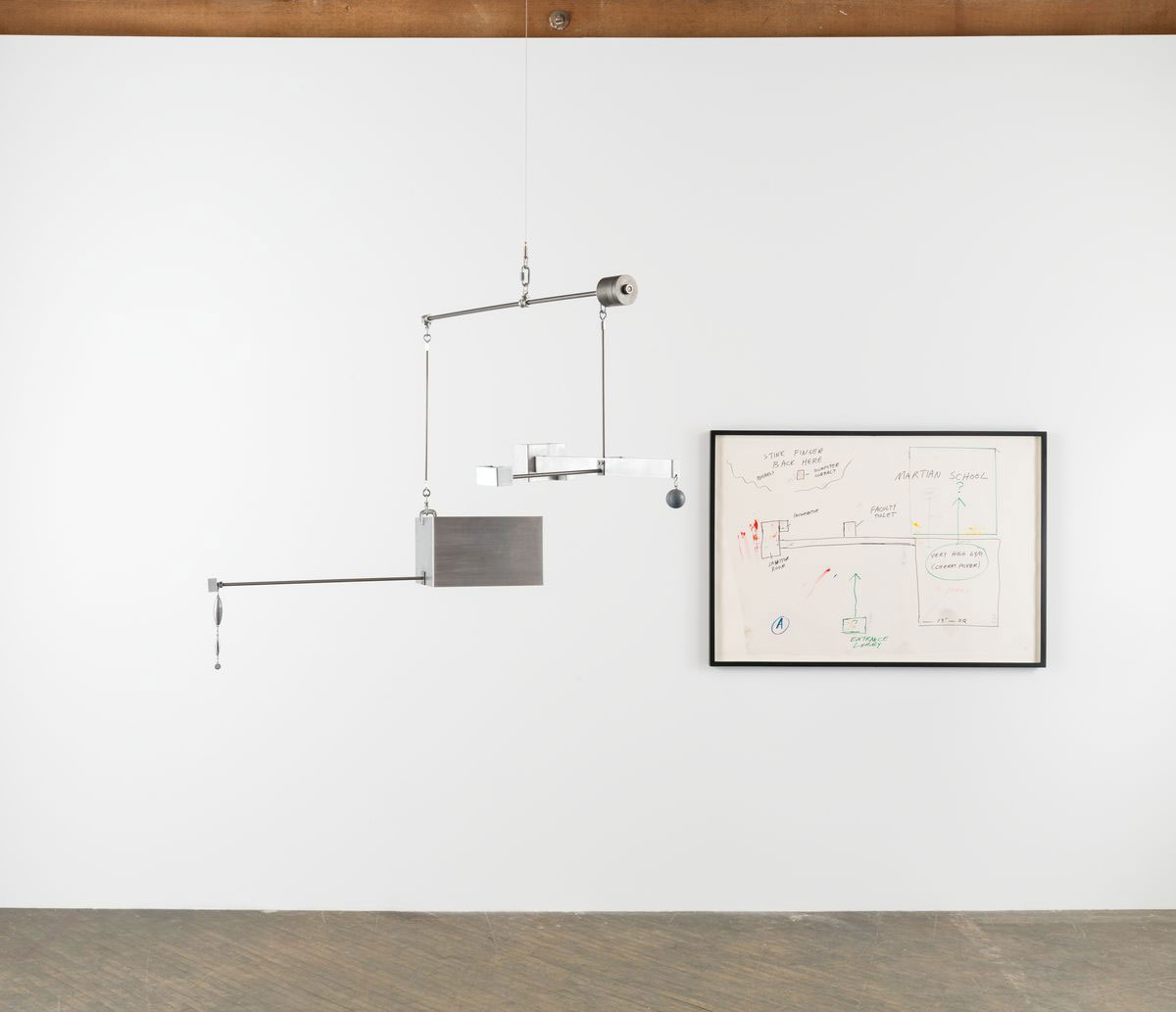

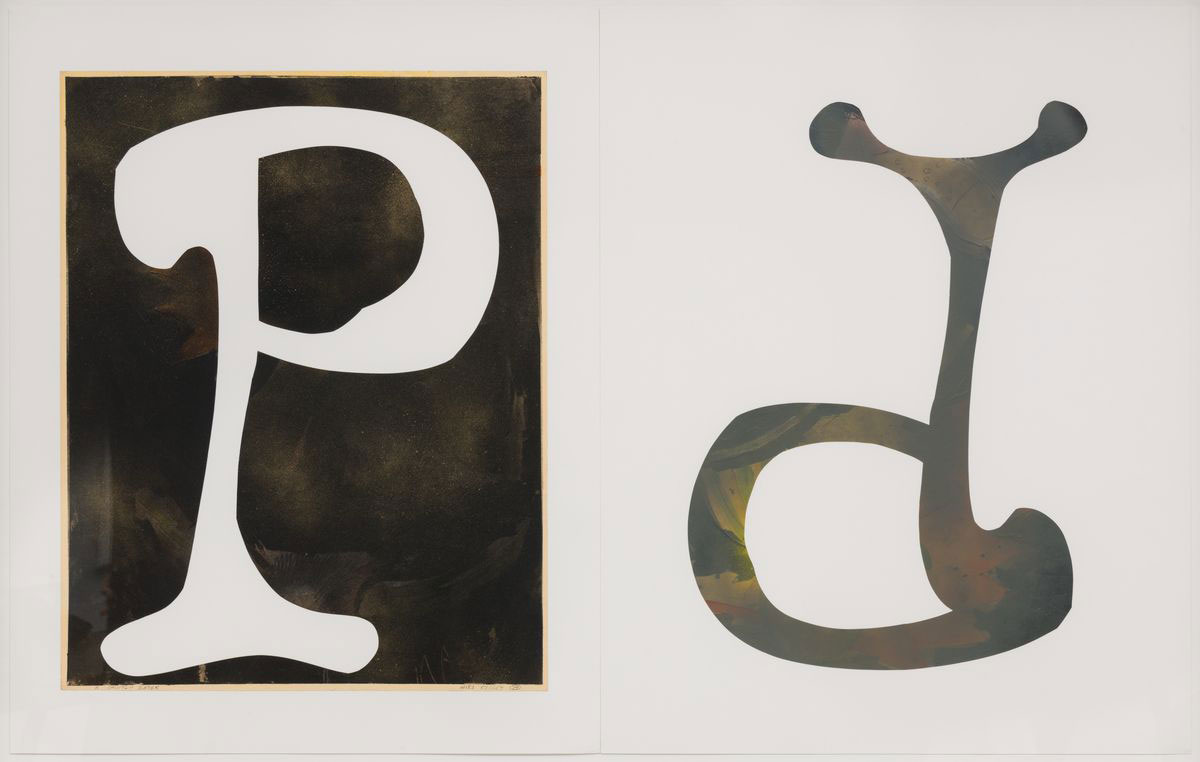

![]() Born in a suburb of Detroit, Mike Kelley grew up in a working class family as the youngest of four children. It was during Kelley’s adolescent years that art-making became a serious career option for him. He decided to become an artist in part because “at that time, it was the most despicable thing you could be in American culture. To be an artist at that time had absolutely no value. It was like planned failure”. Kelley’s parents did not approve of him pursuing such a career, but being the stubborn teenager that he was, he defied them. His father disowned him as a result. While in junior high, Kelley’s art teacher, a closeted gay man who taught crafts, would become a surrogate father, supporting him in his interest in art and later inspiring him to incorporate low-brow culture into his work. Kelley grew up during a time in which Michigan’s cities were facing severe crises caused by rapid deindustrialization, the civil rights movement, and economic downturn. This environment fostered a degree of cynicism in the young Kelley, eventually leading him to embrace the anarchist counterculture. Kelley became an avid participant in both the politically far-left White Panther Party and the underground punk music scene. In 1973, while attending the University of Michigan, he co-founded an improv noise band called Destroy All Monsters. Kelley and fellow artist Jim Shaw quit the band three years later to attend graduate school in California. Enrolling at the California Institute of Arts (CalArts) in 1976, Kelley encountered two teachers who would strongly influence his practice: the conceptual artist John Baldessari and the performance artist and musician Laurie Anderson. Fully embracing the ideals of the avant-garde, Kelley explored as wide a variety of media as possible, including performance, video, writing, and traditional crafts. He also began a second experimental band, The Poetics, with his roommates and fellow installation artists Tony Oursler and John Miller. At CalArts, Kelley was especially drawn to performance art and craft media because each, in different ways, posed a challenge to the category, and accepted practices, of fine art. Graduating in 1978, he opted to remain on the west coast, shunning the lure of the New York art world. After his time at CalArts, Kelley first found success in Europe, with shows in Germany and France garnering particular attention. But while his reputation grew steadily during the 1980s, Kelley’s art-world stardom only fully arrived in the subsequent decade. In 1982 he made his first work in video “The Banana Man” which featured a character indirectly derived from the children’s television show Captain Kangaroo. In 1984 he and two others performed two hours of an eight-hour piece titled “The Sublime” at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. In it Kelley combined a sadomasochistic theme with the philosophical concept of the sublime. Kelley’s performance “Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile” (1985) mocked the belief that the mind can be used to sublimate our physicality. A 1986 Massachusetts Institute of Technology presentation of this work included a live performance by the band Sonic Youth. Kelley subsequently decided to cease performing live and began making objects independent of performances. In the late 1980s he began creating stuffed-animal works from humble, well-worn toys and handmade afghans he purchased at thrift shops. He made his “Garbage Drawings” based on the Sad Sack comics, in 1988. Well received in Los Angeles, Kelley’s art did not meet with success in New York until a 1988 exhibition at Metro Pictures Gallery. 1992, in particular, proved to be a watershed year, marking the beginning of Kelley’s career on the graduate teaching faculty at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, where he would remain a professor until 2007. He acquired a reputation here as a supportive but tough teacher, whose critiques were always brutally honest. Alsom 1992 saw Kelley participate in the landmark group exhibition, “Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s”, at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, along with fellow California artists and collaborators Jim Shaw, Raymond Pettibon, Paul McCarthy, and Chris Burden. The show consisted of artists whose works shared “a common vision in which alienation, dispossession, perversity, sex, and violence either dominate the landscape or form disruptive undercurrents” as the show’s press release proclaimed. Considered among the more important group exhibitions of the early 1990s, Helter Skelter gained a great deal of attention, and finally secured Kelley’s reputation in the United States. In 1993 the artist curated “The Uncanny” an exhibition of unusual interpretations of the body, for Sonsbeek ’93 at the Gemeentemuseum Arnhem in the Netherlands (which was later restaged by the Tate Liverpool in 2004). In addition to his teaching and artistic practice, Kelley remained a prolific writer throughout his career, penning articles and essays on a wide range of subjects from art, film, and architecture to subcultural topics as various as Ufology and Mexican wrestling. As in his art, Kelley himself was a man of contradictions. As the art journalist Kelly Crow reveals, “He hated to drive or fly – his agoraphobia and anxiety growing worse over the course of his life. His artworks earned him a fortune, yet he shopped mainly at secondhand stores and wore a pair of his father’s red loafers for years. He painted just about every bedroom he ever had a particular shade of cucumber green”. Kelley’s “Educational Complex“ (1995), a sprawling architectural model of schools attended by the artist, represents another aesthetic strategy through which the artist remarked on repressed trauma. Kelley revisited the psychologically charged sites and themes of “Educational Complex“ in a series of video installations, “Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction” (2000–05). Taking Los Angeles’ marginalised Chinese-American community as its inspiration, the installation “Framed and Frame (Framed and Frame (Miniature Reproduction “Chinatown Wishing Well” Built by Mike Kelley after “Minature Reproduction ‘Seven Star Cavern’ Built by Prof. H.K.Lu)”, (1999) explores the conceptual space between real and imagined places. The installation recreates a local landmark in the Chinatown of downtown LA and consists of two separate sculptures divided by a wall. “Framed” is a ‘wishing well’ in the form of a biomorphic, concrete, grotto-like landscape, covered with spots of spray-painted color and cheap religious statuary and tossed coins on its ledges and niches. A secret crawlspace complete with a mattress, candles and condoms is revealed at the rear of the well. The adjacent “Frame” is a 2.8 x 4.5 meters enclosure comprised of a cyclone fence, faux brick walls and barbed wire, decorated to resemble a Chinese gate. Initiated by Kelley in 1999, the “Kandors” series comprises numerous representations of Superman’s birthplace, the city of Kandor. The popular Superman story recounts the adventures of an alien being sent to Earth as a baby to escape the total destruction of his home planet, Krypton. However, it turns out that Kandor was not, in fact, destroyed. Shrunk and bottled by the villainous Braniac, the futuristic city was later rescued by Superman and protected under a bell jar in his sanctuary, the Fortress of Solitude. For almost a quarter-century in comic-book time, Kandor and its miniature citizens survived in Superman’s care, sustained by tanks of Kryptonic atmosphere – a constant reminder of his lost past and a metaphor for his psychic disconnection from his adopted planet. In the late ‘90s, Kelley was invited to be part of a group show in Germany, which focused on the impending millennium by exhibiting contemporary art and historical objects with ‘a special emphasis on the “new media” of the past.’ As the artist wrote, “in response to these themes, I decided to create a project that centered on an out-of-date image of the future re-presented through recent technological developments. I chose to focus on the fictional city of Kandor from the Superman comics series”. Kelley originally conceived “Kandor-Con 2000” to be both an interactive convention space and online forum for Superman aficionados, but due to lack of funding, the public new media portions were never realized. Examining the extensive archive he amassed of Kandor’s depiction in Superman comics, Kelley was struck by its sometimes flagrant inconsistencies. He chose twenty diverse examples from the myriad two-dimensional renderings of the sci-fi city in order to create three-dimensional “Kandors” and variant works between 2007 and 2011. In these works, he explores the formal properties of translucency and reflection by casting the Kandors in colored resins, setting them in tinted glass bottles, and illuminating them like reliquaries within specifically designed settings. In 2012, at the age of 57, Kelley committed suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning, just as plans for his first major international retrospective were taking shape.

Born in a suburb of Detroit, Mike Kelley grew up in a working class family as the youngest of four children. It was during Kelley’s adolescent years that art-making became a serious career option for him. He decided to become an artist in part because “at that time, it was the most despicable thing you could be in American culture. To be an artist at that time had absolutely no value. It was like planned failure”. Kelley’s parents did not approve of him pursuing such a career, but being the stubborn teenager that he was, he defied them. His father disowned him as a result. While in junior high, Kelley’s art teacher, a closeted gay man who taught crafts, would become a surrogate father, supporting him in his interest in art and later inspiring him to incorporate low-brow culture into his work. Kelley grew up during a time in which Michigan’s cities were facing severe crises caused by rapid deindustrialization, the civil rights movement, and economic downturn. This environment fostered a degree of cynicism in the young Kelley, eventually leading him to embrace the anarchist counterculture. Kelley became an avid participant in both the politically far-left White Panther Party and the underground punk music scene. In 1973, while attending the University of Michigan, he co-founded an improv noise band called Destroy All Monsters. Kelley and fellow artist Jim Shaw quit the band three years later to attend graduate school in California. Enrolling at the California Institute of Arts (CalArts) in 1976, Kelley encountered two teachers who would strongly influence his practice: the conceptual artist John Baldessari and the performance artist and musician Laurie Anderson. Fully embracing the ideals of the avant-garde, Kelley explored as wide a variety of media as possible, including performance, video, writing, and traditional crafts. He also began a second experimental band, The Poetics, with his roommates and fellow installation artists Tony Oursler and John Miller. At CalArts, Kelley was especially drawn to performance art and craft media because each, in different ways, posed a challenge to the category, and accepted practices, of fine art. Graduating in 1978, he opted to remain on the west coast, shunning the lure of the New York art world. After his time at CalArts, Kelley first found success in Europe, with shows in Germany and France garnering particular attention. But while his reputation grew steadily during the 1980s, Kelley’s art-world stardom only fully arrived in the subsequent decade. In 1982 he made his first work in video “The Banana Man” which featured a character indirectly derived from the children’s television show Captain Kangaroo. In 1984 he and two others performed two hours of an eight-hour piece titled “The Sublime” at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. In it Kelley combined a sadomasochistic theme with the philosophical concept of the sublime. Kelley’s performance “Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile” (1985) mocked the belief that the mind can be used to sublimate our physicality. A 1986 Massachusetts Institute of Technology presentation of this work included a live performance by the band Sonic Youth. Kelley subsequently decided to cease performing live and began making objects independent of performances. In the late 1980s he began creating stuffed-animal works from humble, well-worn toys and handmade afghans he purchased at thrift shops. He made his “Garbage Drawings” based on the Sad Sack comics, in 1988. Well received in Los Angeles, Kelley’s art did not meet with success in New York until a 1988 exhibition at Metro Pictures Gallery. 1992, in particular, proved to be a watershed year, marking the beginning of Kelley’s career on the graduate teaching faculty at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, where he would remain a professor until 2007. He acquired a reputation here as a supportive but tough teacher, whose critiques were always brutally honest. Alsom 1992 saw Kelley participate in the landmark group exhibition, “Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s”, at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, along with fellow California artists and collaborators Jim Shaw, Raymond Pettibon, Paul McCarthy, and Chris Burden. The show consisted of artists whose works shared “a common vision in which alienation, dispossession, perversity, sex, and violence either dominate the landscape or form disruptive undercurrents” as the show’s press release proclaimed. Considered among the more important group exhibitions of the early 1990s, Helter Skelter gained a great deal of attention, and finally secured Kelley’s reputation in the United States. In 1993 the artist curated “The Uncanny” an exhibition of unusual interpretations of the body, for Sonsbeek ’93 at the Gemeentemuseum Arnhem in the Netherlands (which was later restaged by the Tate Liverpool in 2004). In addition to his teaching and artistic practice, Kelley remained a prolific writer throughout his career, penning articles and essays on a wide range of subjects from art, film, and architecture to subcultural topics as various as Ufology and Mexican wrestling. As in his art, Kelley himself was a man of contradictions. As the art journalist Kelly Crow reveals, “He hated to drive or fly – his agoraphobia and anxiety growing worse over the course of his life. His artworks earned him a fortune, yet he shopped mainly at secondhand stores and wore a pair of his father’s red loafers for years. He painted just about every bedroom he ever had a particular shade of cucumber green”. Kelley’s “Educational Complex“ (1995), a sprawling architectural model of schools attended by the artist, represents another aesthetic strategy through which the artist remarked on repressed trauma. Kelley revisited the psychologically charged sites and themes of “Educational Complex“ in a series of video installations, “Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction” (2000–05). Taking Los Angeles’ marginalised Chinese-American community as its inspiration, the installation “Framed and Frame (Framed and Frame (Miniature Reproduction “Chinatown Wishing Well” Built by Mike Kelley after “Minature Reproduction ‘Seven Star Cavern’ Built by Prof. H.K.Lu)”, (1999) explores the conceptual space between real and imagined places. The installation recreates a local landmark in the Chinatown of downtown LA and consists of two separate sculptures divided by a wall. “Framed” is a ‘wishing well’ in the form of a biomorphic, concrete, grotto-like landscape, covered with spots of spray-painted color and cheap religious statuary and tossed coins on its ledges and niches. A secret crawlspace complete with a mattress, candles and condoms is revealed at the rear of the well. The adjacent “Frame” is a 2.8 x 4.5 meters enclosure comprised of a cyclone fence, faux brick walls and barbed wire, decorated to resemble a Chinese gate. Initiated by Kelley in 1999, the “Kandors” series comprises numerous representations of Superman’s birthplace, the city of Kandor. The popular Superman story recounts the adventures of an alien being sent to Earth as a baby to escape the total destruction of his home planet, Krypton. However, it turns out that Kandor was not, in fact, destroyed. Shrunk and bottled by the villainous Braniac, the futuristic city was later rescued by Superman and protected under a bell jar in his sanctuary, the Fortress of Solitude. For almost a quarter-century in comic-book time, Kandor and its miniature citizens survived in Superman’s care, sustained by tanks of Kryptonic atmosphere – a constant reminder of his lost past and a metaphor for his psychic disconnection from his adopted planet. In the late ‘90s, Kelley was invited to be part of a group show in Germany, which focused on the impending millennium by exhibiting contemporary art and historical objects with ‘a special emphasis on the “new media” of the past.’ As the artist wrote, “in response to these themes, I decided to create a project that centered on an out-of-date image of the future re-presented through recent technological developments. I chose to focus on the fictional city of Kandor from the Superman comics series”. Kelley originally conceived “Kandor-Con 2000” to be both an interactive convention space and online forum for Superman aficionados, but due to lack of funding, the public new media portions were never realized. Examining the extensive archive he amassed of Kandor’s depiction in Superman comics, Kelley was struck by its sometimes flagrant inconsistencies. He chose twenty diverse examples from the myriad two-dimensional renderings of the sci-fi city in order to create three-dimensional “Kandors” and variant works between 2007 and 2011. In these works, he explores the formal properties of translucency and reflection by casting the Kandors in colored resins, setting them in tinted glass bottles, and illuminating them like reliquaries within specifically designed settings. In 2012, at the age of 57, Kelley committed suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning, just as plans for his first major international retrospective were taking shape.