ART CITIES:London, Gordon Matta-Clark

The son of the Surrealist painter Roberto Echaurren Matta, Gordon Matta-Clark was educated as an architect, but was drawn away from the formal practice of architecture and attracted to art. During the brief but highly productive decade that he worked as an artist he has exerted a powerful influence on artists and architects and has emerged as a key figure of the generation that came after Minimalism.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: David Zwirner Gallery Archive

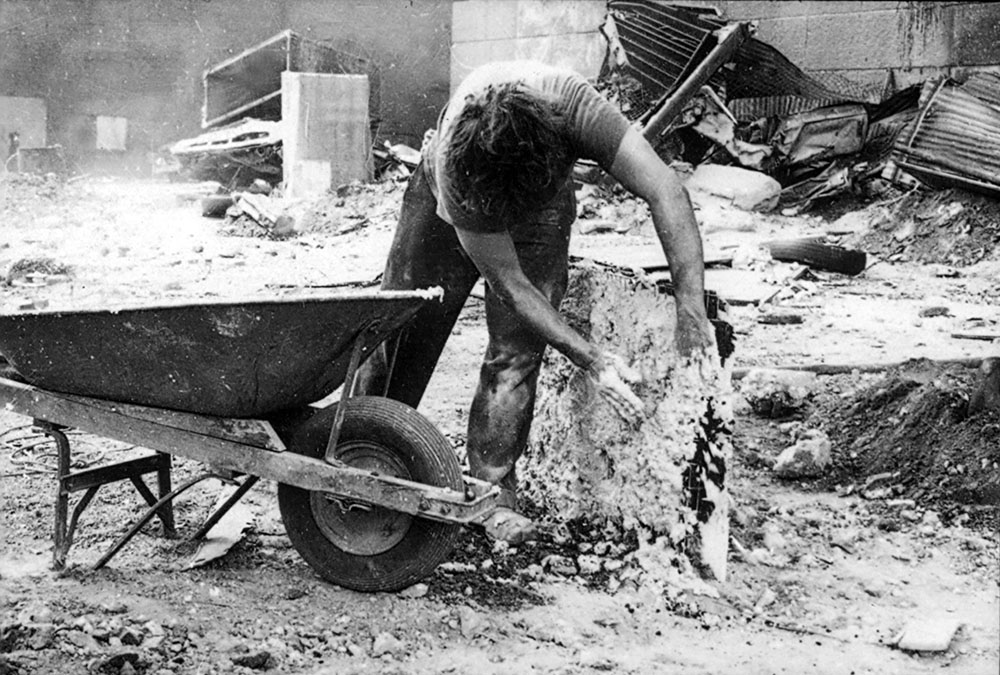

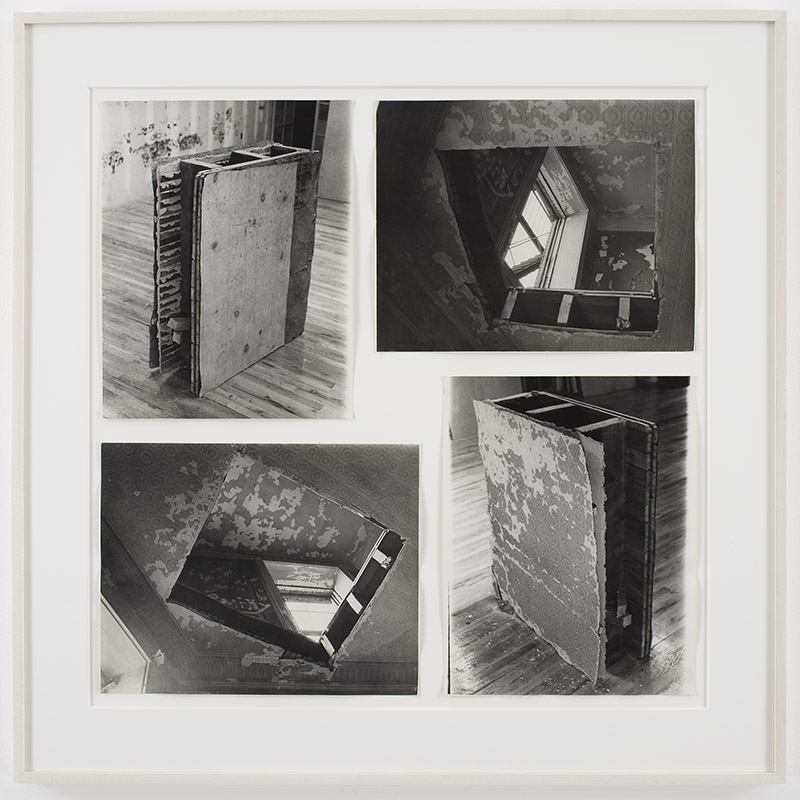

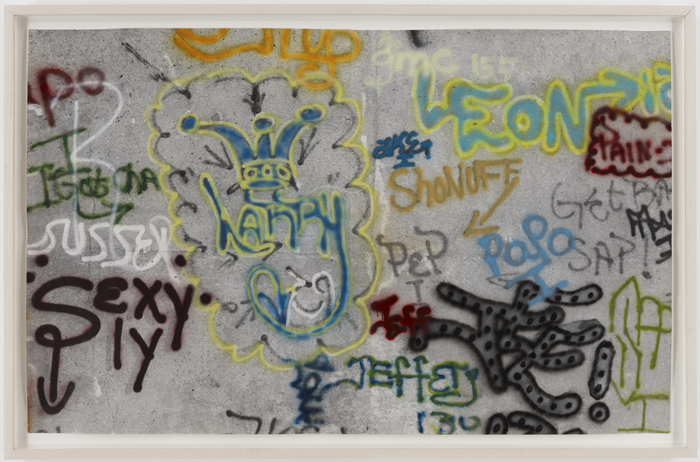

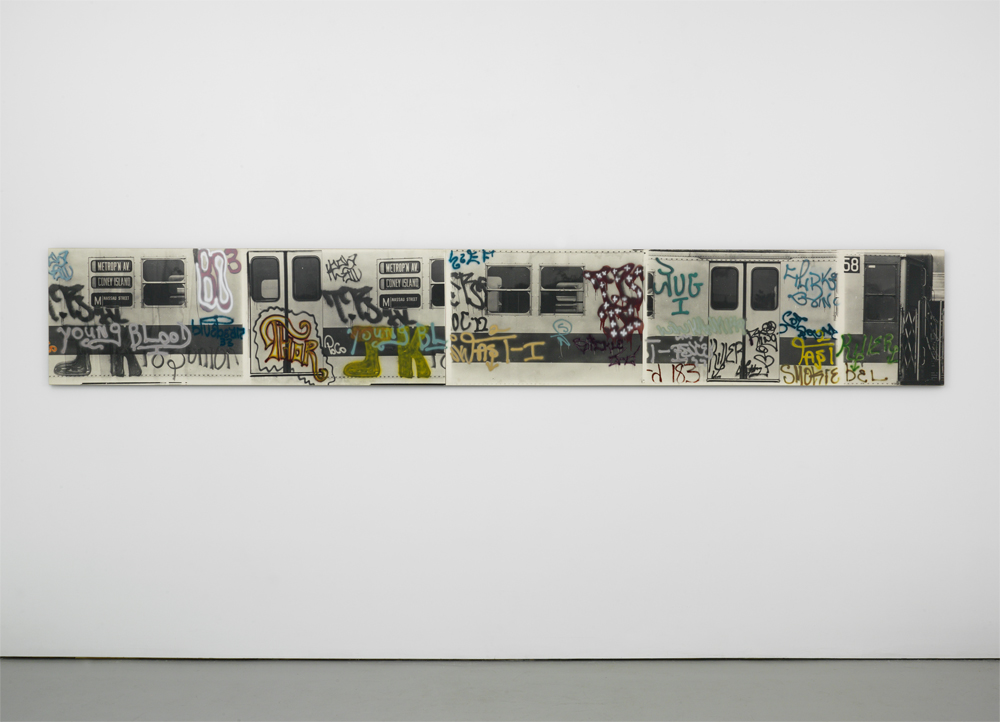

The exhibition “Works 1970–1978” includes key examples from the Gordon Matta-Clark’s short but prolific career, including films, photographs, sculptures, and works on paper that illustrate his complex engagement with architecture and the many ways in which he reconfigured the spaces and materials of everyday life. Films and photographs are among the only surviving records of Matta-Clark’s ephemeral projects; they were used by the artist not only for documentation, but also as an essential means to explore some of the major ideas underpinning his practice. On view ise a selection of newly remastered films by Matta-Clark documenting some of his seminal works, including “Splitting” (1974) and “Sous-Sols de Paris” (1977), in which he explored a complex network of underground structures in Paris. A central figure of the downtown New York art scene in the 1970s, Matta-Clark pioneered a radical approach to art making that directly engaged the urban environment and the communities within it. Gordon Matta-Clark studied architecture at Cornell University in 1963–68. At the 1969 exhibition “Earth Art” at Cornell, he met Robert Smithson and helped Dennis Oppenheim construct two projects. Like the earth artists, Matta-Clark would reject the commodification of art, eventually working in photography, film, video, Performance, drawing, photo collage, and sculpture in the form of large-scale interventions into existing architecture and evolved into a kind of urban land artist who used his skills to reshape and transform architecture into an art of structural explication and spatial revelation. Matta-Clark made his first “Garbage Wall” at St. Mark’s Church in the East Village in 1970. Originally conceived as the ephemeral set for a performance, it mixed garbage with concrete. But Matta-Clark soon saw that combination had possibilities for both cheap housing and communal art; either way it was something that could be made by anyone. The artist intended for this wall to be rebuilt and adapted to different locations by using found garbage from the specific city in which it is made. His activity in the early 1970s included some of his first architectural cuts, among them “Claraboya” (1971), represented here by a set of photographs documenting the project from various vantage points. In this project, he carved a square hole from the men’s bathroom on the basement level of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Santiago, Chile, all the way up to the roof, installing mirrors throughout the length of the incision to bring light into the otherwise darkened space. This process of subtraction brought the outside world in and would become one of the artist’s primary working methods, informing significant future projects such as “Bronx Floors” (1972-73), “Splitting” (1974), “Bingo” (1974), “Day’s End” (1975), “Conical Intersect” (1975), “Office Baroque” (1977), and “Circus” (1978). “Bronx Floors” (1972-73): Some of Matta-Clark’s first interventions in the urban architectural fabric were the pieces of floor (including the beams and ceilings beneath them), roughly four-feet square, that he cut from abandoned buildings in the South Bronx. In 1973, Matta-Clark witnessed a growing graffiti culture in New York; enlivened by the changing urban environment and the proliferation of street art, he began photographing tags throughout the city, selectively hand-colouring some of the resulting prints to bring out the vibrancy of the graffiti. Matta-Clark continued to experiment with color in his photographs later toward the end of his career, making large-format Cibachrome prints, then a relatively new process made from color transparencies, which he favoured for their deeply saturated hues. Cutting up and enlarging 35-millimetre slides, which he then collaged, gave the artist the opportunity to express in more detail notions of scale and perspective and to describe the vertiginous instability that often resulted from his architectural cuts. One of Matta-Clark’s long-gone masterpieces is “Day’s End” (1975) a site-specific piece executed without permits on one of the decrepit piers on the Hudson River in the West Village, which then served mainly for assignations among gays. Matta-Clark was after light and water views. He cut a big semicircle through the corrugated steel end-wall of the piece. This half-moon, orange slice or primitive rose window was echoed, just inside the building, by a large quarter-circle cut through the heavy floor (but not the beams) to reveal the river below. After New York City officials discovered “Day’s End” Matta-Clark faced an arrest warrant and lawsuit. He went to Paris and remained there until charges were dropped. Created for the 9th Paris Biennale, “Conical Intersect” (1975) coincided with a daunting process of urban interventions in Paris that entailed a reorientation of circulation flows, new housing developments, and the revitalization of the city’s historic center. The work consisted of a cone hollowed out of two derelict 17th Century buildings next to the site where the glaring, industrial-looking structure of the future Centre Pompidou was rising amid the medieval an prerevolutionary buildings in the very center of Paris. “This old couple” Matta-Clark noted, “was literally the last of a vast neighborhood of buildings destroyed to ‘improve’ the Les Halles–Plateau Beaubourg area”. A traditional marketplace since the middle ages, Les Halles became the city’s commercial core in the early 19th Century. Its destruction was highly controversial and both the left and the right criticized Matta-Clark for his participation in and critique of this “urban renewal”. The design of the cut was inspired by Anthony McCall’s “Line Describing A Cone” (1973) and can also be seen as a para-cinematic work: the cone shape functioning as a kind of lens looking down from the new Beaubourg (the future) through the derelict cut buildings (the past) and opening up onto the everyday street scene (the present).

Info: David Zwirner Gallery, 24 Grafton Street, London, Duration: 21/11-20/12/18, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, www.davidzwirner.com