ART-PRESENTATION: Something Is Slowly Moving In A Different Direction, Part I

The Sami are the indigenous people living in the very north of Europe, in Sápmi, which stretches across the northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Kola Peninsula. Although regarded as one people, there are several kinds of Sami based on their patterns of settlement and how they sustain themselves. Furthermore, their rights and general situation differ considerably depending on the nation state within which they live. 2017 marks the centennial for the first Sami gathering, which took place in Trondheim–Tråante (Part II).

The Sami are the indigenous people living in the very north of Europe, in Sápmi, which stretches across the northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Kola Peninsula. Although regarded as one people, there are several kinds of Sami based on their patterns of settlement and how they sustain themselves. Furthermore, their rights and general situation differ considerably depending on the nation state within which they live. 2017 marks the centennial for the first Sami gathering, which took place in Trondheim–Tråante (Part II).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: : Kunsthall Trondheim Archive

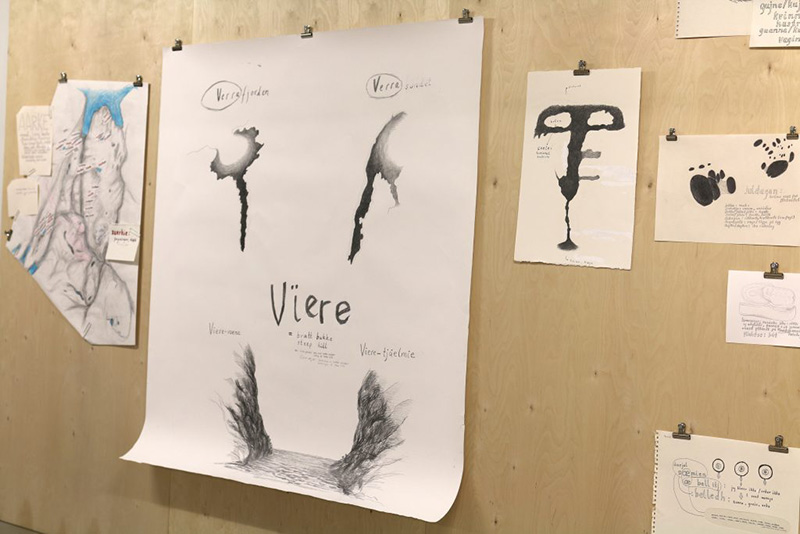

The group exhibition “Noe beveger seg sakte i en annen retning” (something is slowly moving in a different direction) presents five young Sami artists together with one of the most influential and well known: Iver Jåks. The title of the exhibition refers both to Iver Jåks view on art and to an increasing interest and respect for the Sami cultures. Visibility and pride are growing alongside processes of rewriting of history and an interest for language. Iver Jåks thought of his works as in constant process, they are meant to ultimately fall apart, disintegrate and be gone, subject to the same processes, which forms the foundations for the rest of our lives. The small sculptural works in wood, reindeer horn or stone can be installed in different ways. There is never just one perfect choice, not a fixed point of view.The work of the hand is always at the core, the connection to context, nature and the human always central. Iver Jåks’ oeuvre was one of transformation. Ragna Misvær Grønstad’s work process takes place in what in Sami mythology is called Sáivu, a lake with a double bottom, below which a parallel world is found. This poetic and imaginary room allows for blurred boundaries between reality and imagination and for meetings and discussions with people whose thoughts and writings are important sources for the artist, among them: Guy Debord, Hannah Arendt and Gaston Bachelard. Out of these visits and encounters come large wood engravings, which the artist describes as doorways, and drawings. It’s a floating universe, full of fish and seaweed and salt water flowers – a subaquatic herbarium of plants, thoughts and narratives. Silje Figenschou Thoresen in her work “Vandret linje” performs a re-appropriation of Sami history. The drawings are copied from descriptions of the archaeological findings in Northern Norway by Danish archaeologist and professor at Tromsø University Povl Simonsen. He was the first to prove, in the ‘50s, that the Sami people had lived in the area since the land was free of ice, still a controversial statement since many legal issues concerning land rights are informed by history. The objects in her installation on the other hand are not what normally would be considered archaeological objects, Sami objects has often “Picked apart and re-used, hoarded, stored, used, burned, left to rot” and hence been invisible for the scientist’s eye. The repressed Sami history is also the focus for Sissel M. Bergh, who investigates how the South Sami language, spoken around the Trondheim area, has influenced names on places, animals, plants and forms in nature in an ongoing project. The etymology of local words, a discipline in which the Sami presence in the region has been made invisible, now has to be reconsidered. As with archaeology, etymology is an area of knowledge, which carries political implications. The impact of losing connections to the past, through history and language, is expressed in the large root installation. Niilas Helander’s work highlights genealogy and another hidden part of Sami history in his work, the history of those who are not reindeer herders. While the Sami reindeer herder for many stands as a symbol for the Sami culture, the fishing or farming Sami communities have had less visibility and presence. The artist uses the measurements of his grandfathers fishing hut as a starting point for his installation “This is genealogy”, the work is a reminder of the variety of Sami cultures. It also points to labour and social class as factors not often included in the discussion. Identity and politics are also central topics in Carola Grahn’s work, and often expressed in writing. In this exhibition she presents works that she describes as a form of materialized writing about body, ethnicity and belonging. “Notes on hide” are fragmented and framed thoughts, abstract and yet physical. The reindeer hide is in itself a political reference to the lack of indigenous rights, and a violent history, but it also talks about warmth and humour. Her series of wooden sculptures brings forward physical work as a form of social intercourse and the joy of working together. The sculptures take the shape of woodpiles, connecting them to the comfort of home and nature.

Info: Kunsthall Trondheim, Kongens gate 2, Trondheim, Duration 1/6-3/9/17, Days & Hours: Tue-Thu 12:00-20:00, Fri-Sun 12:00-18:00, http://kunsthalltrondheim.no