INTERVIEW: Ricardo Brey

Ricardo Brey does not need an introduction. He is a very important contemporary artist, not afraid to create and deconstruct at the same time his artwork, but supports it consciously. Ηis work is deeply spiritual, poetic and totally contemplative, raised through the plurality of expressive media and visual arts. On the occasion of his solo show “All that is could be otherwise” at the Galerie Nathalie Obadia in Paris, we are discussing about his new works shown in the exhibition, his sources of inspiration and his concerns as they reflect into his artwork.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Galerie Nathalie Obadia Archive

Portrait Ricardo Brey, Photo : Alina Sardiña, Havana

Artworks Images : © Ricardo Brey

Mr. Brey in “All that is could be otherwise”: Trough photo based works printed on canvas and installations, you deal with a primitive issue with many different extensions and multiple readings, which include the local as well as the international. As we know draw your inspiration directly from your birthplace, Cuba, which underwent massive deforestation. What does this act means for you and how affected you?

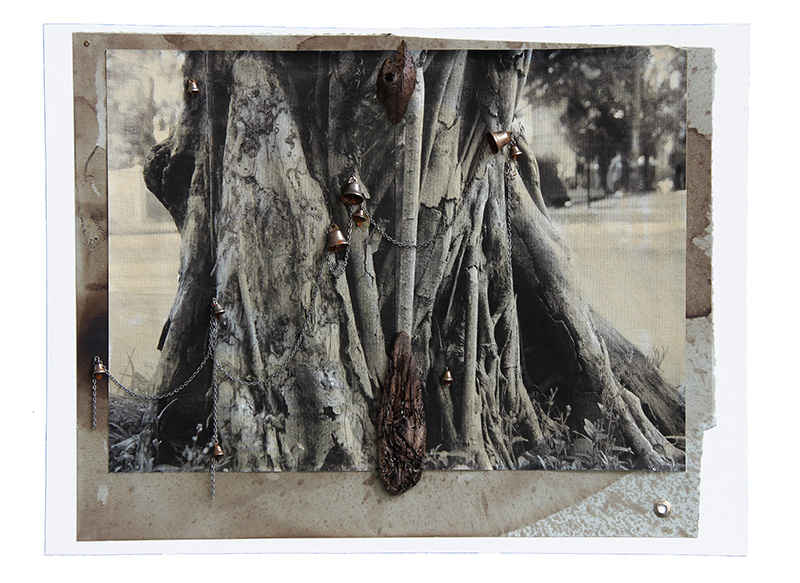

The most iconic Cuban painting of the XX Century was made by the artist Wifredo Lam, the name of the painting is La Jungla (The Jungle). I mention this to emphasize how important the relationship of the Cuban people with the natural world is. Part of this tradition comes from Africa, another part from Spain. When I went back to Cuba after 25 years without visiting my homeland, I found out that this relationship was broken. The urgent need of fuel during the hard times in the 90’s , called Periodo Especial made the population see the trees as fuel and not as a source of medicine, wisdom or shade. Even millenaire trees were torn down. Today this is still happening. Trees in public or private spaces are indiscriminately felled and across the city there are the vestiges of what once were magnificent trees, now turned into ashes. Where there was shade and coolness there is now a suffocating heat. We must add to this the loss of memory and blindness of the people toward this tragedy. They no longer remember how this happened or even remember the trees themselves. People feel untouched that this is occurring. More than once I was told that these trees slowly, as if by magic, ignite and burn themselves.

In the photographic images that I took there, I try to superimpose the two floating energies that this barbaric act brings to the surface. I want to stress that it is not only the trees that disappear, but the memory as well. With the roots of the trees in the air, the roots of the human psyche start to perish.

These photos suggest a negative energy being exorcised, they are turned into three-dimensional installations through objects and the relations between them, searching to create a new image. Drifting around the urban environment, they are another layer of reality, another jolt to see reality.

Nevertheless, I think this clearance is not just happening in Cuba, it is happening everywhere in different scales and implications. In a survey exhibition I had in 2013 in the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de La Habana, I presented this work for first time. I wanted to bring focus to this and send a wake up call. On the other hand, because the people familiar with my work were expecting a big show of drawings on paper I chose to shift the attention to another corner that was more appealing.

Observing all your work we note that very often you are using paper that is a direct product from the tree. What is the role of the paper in your visual vocabulary? What is its importance in the creation of visual icons in your work and the expression of your ideas?

If I say which action is the most defining at the moment in my praxis, it is the search for materials and mediums that could bring an extra quality to the images that I create.

If I made one installation, for example, I am drawing in the space. Every material needs to bring special properties to that drawing. What I want to say is that for me, drawings are not just bound to work on paper, which is the obvious medium.

If I interrogated one specific material, it would probably answer with the qualities that define its existence – texture, size – and the meaning that we have historically provided to this material. This could be the center of one of my drawings -installation – photo – sculpture.

Specifically my drawings on paper have a long relationship with me, one that has already lasted for over 40 years. It is very flexible. For long periods I do not need to make drawings, I concentrate more on sculptures for example, but I know that I am accumulating energy and resources to start again.

In a way, my works on paper consist of a kind of parallel activity, that even though it is always there, it is far less visible than my installations and sculptures. What you see is the tip of the iceberg, drawings on paper are for me almost a field of private research in which ideas and forms mature at different, slower rates than those imposed by exhibition deadlines.

After the experience of making the installation Universe in 2002, which consists of 1004 drawings that are displayed in 99 vitrines, my relationship with the drawings has become more calm, more reflexive. They grow hand in hand with the ideological basis of my work, which is not one of iconography, but one of thought.

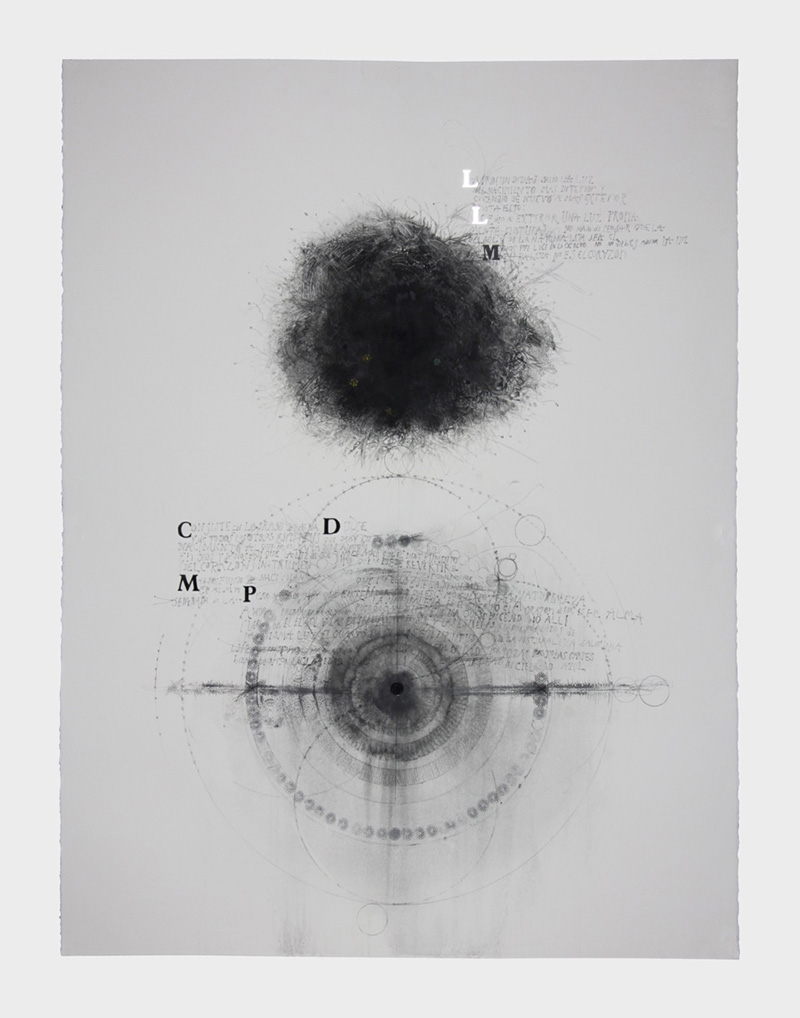

In your artwork entitled “Inferno” (2016), you are referring in the text “Dos lecciones infernales” by Galileo Galilei, from which you extract words and excerpts in order to give shape to your ideas, sounds and thoughts that inspire you. Is paper the field-material that allows you to leave your mark in the world?

From a historical perspective, great masters used the Inferno as a reference to make a big part of their work. William Blake, Botticelli, Dore, Dali, Rauschenberg to name only few. All of them have made works that inspired myself over the years.

In these moments of social and political uncertainty the Inferno is a good starting point for discussion. Do not think the Inferno stayed in the past. It is here in the present and hopefully avoiding ecological and social disasters we will be able to close its door in the future.

I checked my ego this morning and he told me, he was ok. I am not so pretentious to think I will leave a mark upon the world.

I love making art: It is a constant source of joy and disappointment. We need to find a center to the Universe, and the Inferno could be a good starting point. If we exorcise our demons and know the exact place where they are, we will probably be better at fighting against them or at least at having them under control.

I placed a mirror in the center of this work, with the hope that everyone sees their own image at the center of this darkness and will desire a way out. Art is another tool to raise our awareness.

The angle that I find appealing in this new large format drawings comes from the conferences of Galileo, a scientific who used the words of a Poet, -Dante Alighieri-, as a reality. As a scientific he wanted to prove that he could measure and evaluate the reality that was presented in the poem. Part of my previous works, early works from the 80’s, were dealing with scientifics ( Humboldt, Darwin,… ) that in their assessment, and description of the natural world, not only classified and measured what they saw but they brought elements of poetry into it.

This apparent conflict of science versus art, rational versus irrational, atheism versus religion, is what I want to place in these new drawings

Those conferences have given me the possibility of not dealing directly with Dante’s texts and have allowed me to approach the subject of Inferno and different themes of the Divine Comedy. Through Galileo’s study of Dante. With an open mind for different materials and techniques, I have reconciled in my drawings my interest for poetry, philosophy, religions, sciences, the individual, present history and contemporary society. The possibility of melting thoughts and meanings in a single work is one of the pillars of all my works. What you see is, hopefully, one of many layers.

In “All that is could be otherwise”, you worked around the Korean word “Hallyu”, which associates quick cultural dissemination to the motion of a wave. Do you consider that in our era, that with the help of technology and new media which allows everybody to have access in information, Art and Culture are in a better position from the past or this is double-edged sword?

It is not double-edged sword. It is more of a Swiss Army Knife, with many functions and many keys, the last key being that of fake news and look where that has taken us.

Looking for wise words of relief, I once more started reading the German philosopher Hans Jonas. He wrote this important book, The Imperative of Responsibility: In Search of Ethics for the Technological Age. In this book he traced one of the moral and ethical dilemmas of our time. It is not my area of expertise. There are people more capable of giving a better answer to all these problems that arise in every technological step. In my opinion, we can see that every technological step we take brings mostly to a dark side, a Pandora’s box.

I use the word “Hallyu” because it is quite opposite to the WIND OF REVOLUTIONS. It is a persistent whispering which reminds me of the character that in the Chinese book of Tao is given to another natural element, the water. Water is strong because it is ductile, “Hallyu” is strong because it is persistent. The wind that molds the stone is not a harsh wind, that hard wind just breaks the rock and makes it fall. A persistent wind molds the rock in time and mostly creates sand with the same “wisdom” as the rock.

Mr. Brey, you are an artist that finally, does not afraid to create and deconstruct at the same time you artwork, which is spiritual and truly poetic with international character, with quests and concerns that essentially affect the public as they is negotiating with the meanings of the space, of the time, of the place and eventually with the chaos. How do you believe that we can rebirth from chaos?

In my opinion there are no magic bullets or formulas that can answer this. During years of research I have read books from authors such as Edward N. Lorenz and Lynn Margulis. Those lectures, amongst others, helped me to create my way of working.

I always improvise and until now that has proven to be a very effective approach. If we rationalize too much what we create can be messy, shabby, but not chaotic. The representation of the Chaos needs to be multiple, amorphic, moody.

I remember once I was making one installation in a museum in Japan, and without knowing a journalist was observing me, sort of trying to discover my working methodology. Afterwards he told me that it was like I had arrived with a moving van and just had thrown everything out, but suddenly everything came together in an art work .I was methodically engaging chaos. I was creating chaos. But just was sort of a lesson in methodology because in fact I was painting in the space, drawing in the space, and working to create an artwork consciously constructed to leave things looking like I had done nothing at all.

It is a word that defines my new approach to the Chaos: Ungrund. This word helps me with the works on paper on which I have been busy since 2009. I find this word very interesting; it is juicy with multiple images and hard to define. It is a word from a text by Jacob Boehme. He was a philosopher, a shoemaker that one day saw the origin of the creation in the reflection of a silver pewter plate.

I do not know how we can be reborn from chaos, the only thing I can say is that the roots of my work come from the mess that another left before me. Form which I try very hard to make sense, improvise with them and deliver them as an art form.

First Publication: www.dreamideamachine.com

© Interview-Efi Michalarou

ALL ANSWERS ARE © Copyright of Ricardo Brey

Info: Galerie Nathalie Obadia, 18 rue du Bourg-Tibourg, Paris, Duration: 7/1-25/2/17, Days & Hours: Mon-Sat 11:00-19:00, www.nathalieobadia.com