ARCHITECTURE: Gordon Bunshaft

Architect Gordon Bunshaft (9/5/1909-6/8/1990) was responsible for some of the earliest and most famous “corporate modernist” buildings. He was hired as a designer with the architectural firm of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) in 1937, and became a partner in the firm twelve years later. His were among the first “glass box” skyscrapers, a style that was often breathtaking when designed by Bunshaft but became dull in the hands of lesser architects.

Architect Gordon Bunshaft (9/5/1909-6/8/1990) was responsible for some of the earliest and most famous “corporate modernist” buildings. He was hired as a designer with the architectural firm of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) in 1937, and became a partner in the firm twelve years later. His were among the first “glass box” skyscrapers, a style that was often breathtaking when designed by Bunshaft but became dull in the hands of lesser architects.

By Dimitris Lempesis

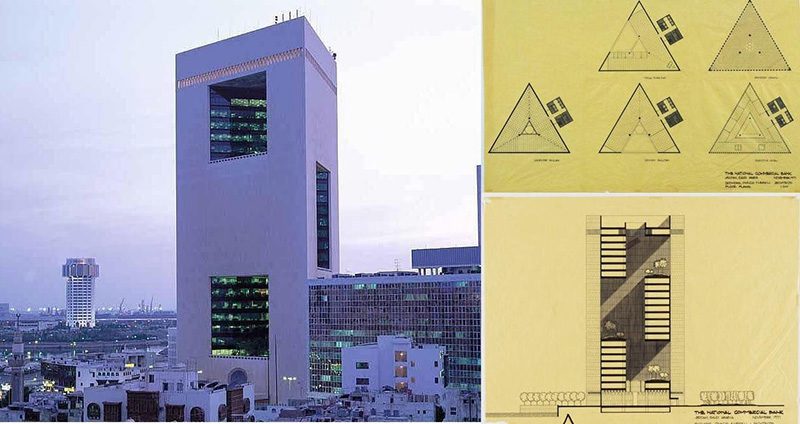

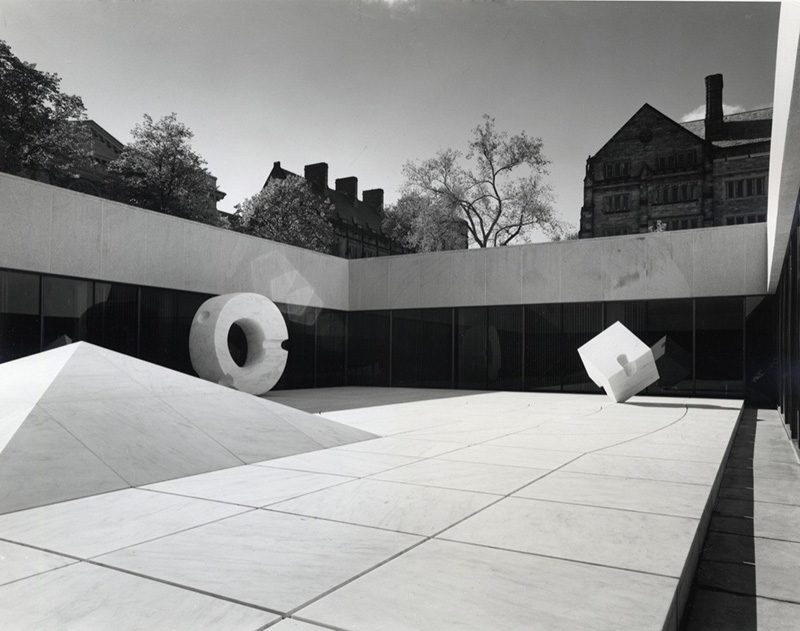

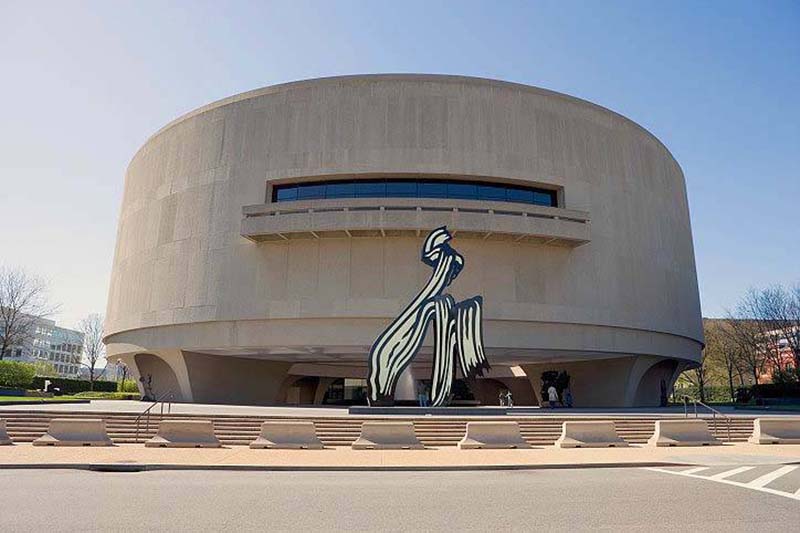

Gordon Bunshaft was born, and raised in Buffalo, New York. He was determined to become an architect from his childhood, he studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This education was followed by a study tour of Europe on a Rotch Traveling Fellowship (1935-1937). In 1937, after working briefly for the architect Edward Durell Stone and the industrial designer Raymond Loewy, Bunshaft entered the New York City office of Louis Skidmore. Skidmore had formed an architectural firm with Nathaniel Owings in 1936, which John O. Merrill joined in 1939 to form Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). Other than serving in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers between 1942 and 1946, Bunshaft remained with SOM until his retirement in 1979. By the late 1940s he was a partner and chief designer in the New York office. Because of SOM’s emphasis on teamwork, and the fact that his name was not a part of the firm’s name, Bunshaft was perhaps not as well known as many of the other major architects of the post-1945 period. Nonetheless, several of his designs have become landmarks in the history of architecture. He preferred to express his ideas primarily through building, rather than writing or speaking. Bunshaft’s most significant early design was Lever House (1951-1952) on Park Avenue in New York. Breaking from the ziggurat-like masses of the previous generation of New York skyscrapers, Bunshaft’s tower was a seemingly weightless glass box. The pilotis, roof garden on the lower block, and dramatic sculptural quality of these pristine geometric forms were reminiscent of the architecture of Le Corbusier, whom Bunshaft had met in Paris during World War II. However, the use of large areas of glass, metal frames, and a meticulous concern for precise details were closer to another master of modern architecture, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Lever House was one of the central links in transforming the radical International Style of the ‘20s and ‘30s into the dominant architectural expression for American corporations during the ‘50s and ‘60s. The era of the “glass box” skyscraper, which Lever House helped to foster, was often criticized for its redundancy and lack of originality. However, in the hands of Bunshaft this minimal approach to skyscraper design often became a high art form, such as his simple and elegant composition for the Pepsi-Cola Company in New York. In the design for the Chase Manhattan Bank and Plaza in New York, Bunshaft showed finesse in housing diverse functions within the clarity and order of a single rectangular block of steel and glass rising up 60 stories. Along with defining the architectural character of corporate America in cities, Bunshaft built several significant designs for corporate headquarters in suburban and rural areas. Rather than rising vertically, these modern buildings spread out horizontally across arcadian settings in a palace-like manner, such as the two examples in Bloomfield, Connecticut: the Connecticut General Life Insurance Company Headquarters and the Emhard Manufacturing Company Administration and Research Building. Bunshaft was an avid collector of modern art and often worked with artists to bring sculptures into a correspondence with buildings. Bunshaft’s interest in sculpture was further suggested in the monumental character of many of his designs for institutions. Bunshaft further explored the bold and dramatic use of singular monumental forms in his formalist temple, with Egyptian-like sloping walls, for the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library at the University of Texas, Austin, and the cylindrical, bunker-like Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. His last project before retiring from SOM was the National Commercial Bank in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, completed in 1983. At three different levels, on each side of the building are loggias that Mr. Bunshaft called “Gardens in the air”. He acknowledged, “I think this is one of my best and most unique projects”. He received numerous awards, including the 1984 Gold Medal of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. In 1988 he and fellow architect Oscar Niemeyer of Brazil shared the Pritzker Architecture Prize. Bunshaft died at the age of 81.

Gordon Bunshaft was born, and raised in Buffalo, New York. He was determined to become an architect from his childhood, he studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This education was followed by a study tour of Europe on a Rotch Traveling Fellowship (1935-1937). In 1937, after working briefly for the architect Edward Durell Stone and the industrial designer Raymond Loewy, Bunshaft entered the New York City office of Louis Skidmore. Skidmore had formed an architectural firm with Nathaniel Owings in 1936, which John O. Merrill joined in 1939 to form Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). Other than serving in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers between 1942 and 1946, Bunshaft remained with SOM until his retirement in 1979. By the late 1940s he was a partner and chief designer in the New York office. Because of SOM’s emphasis on teamwork, and the fact that his name was not a part of the firm’s name, Bunshaft was perhaps not as well known as many of the other major architects of the post-1945 period. Nonetheless, several of his designs have become landmarks in the history of architecture. He preferred to express his ideas primarily through building, rather than writing or speaking. Bunshaft’s most significant early design was Lever House (1951-1952) on Park Avenue in New York. Breaking from the ziggurat-like masses of the previous generation of New York skyscrapers, Bunshaft’s tower was a seemingly weightless glass box. The pilotis, roof garden on the lower block, and dramatic sculptural quality of these pristine geometric forms were reminiscent of the architecture of Le Corbusier, whom Bunshaft had met in Paris during World War II. However, the use of large areas of glass, metal frames, and a meticulous concern for precise details were closer to another master of modern architecture, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Lever House was one of the central links in transforming the radical International Style of the ‘20s and ‘30s into the dominant architectural expression for American corporations during the ‘50s and ‘60s. The era of the “glass box” skyscraper, which Lever House helped to foster, was often criticized for its redundancy and lack of originality. However, in the hands of Bunshaft this minimal approach to skyscraper design often became a high art form, such as his simple and elegant composition for the Pepsi-Cola Company in New York. In the design for the Chase Manhattan Bank and Plaza in New York, Bunshaft showed finesse in housing diverse functions within the clarity and order of a single rectangular block of steel and glass rising up 60 stories. Along with defining the architectural character of corporate America in cities, Bunshaft built several significant designs for corporate headquarters in suburban and rural areas. Rather than rising vertically, these modern buildings spread out horizontally across arcadian settings in a palace-like manner, such as the two examples in Bloomfield, Connecticut: the Connecticut General Life Insurance Company Headquarters and the Emhard Manufacturing Company Administration and Research Building. Bunshaft was an avid collector of modern art and often worked with artists to bring sculptures into a correspondence with buildings. Bunshaft’s interest in sculpture was further suggested in the monumental character of many of his designs for institutions. Bunshaft further explored the bold and dramatic use of singular monumental forms in his formalist temple, with Egyptian-like sloping walls, for the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library at the University of Texas, Austin, and the cylindrical, bunker-like Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. His last project before retiring from SOM was the National Commercial Bank in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, completed in 1983. At three different levels, on each side of the building are loggias that Mr. Bunshaft called “Gardens in the air”. He acknowledged, “I think this is one of my best and most unique projects”. He received numerous awards, including the 1984 Gold Medal of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. In 1988 he and fellow architect Oscar Niemeyer of Brazil shared the Pritzker Architecture Prize. Bunshaft died at the age of 81.