TRIBUTE: Moki Cherry-A Journey Eternal

Moki Cherry was typical of her age, but also a trailblazer. In the ‘70s, when many artists challenged the authorities, Moki Cherry based her artistic practice not on pointing out faults, but on promoting the values that were actually worth protecting and fighting for. A kind of utopian alternative – what life should we lead, and how?

Moki Cherry was typical of her age, but also a trailblazer. In the ‘70s, when many artists challenged the authorities, Moki Cherry based her artistic practice not on pointing out faults, but on promoting the values that were actually worth protecting and fighting for. A kind of utopian alternative – what life should we lead, and how?

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Moderna Museet Archive

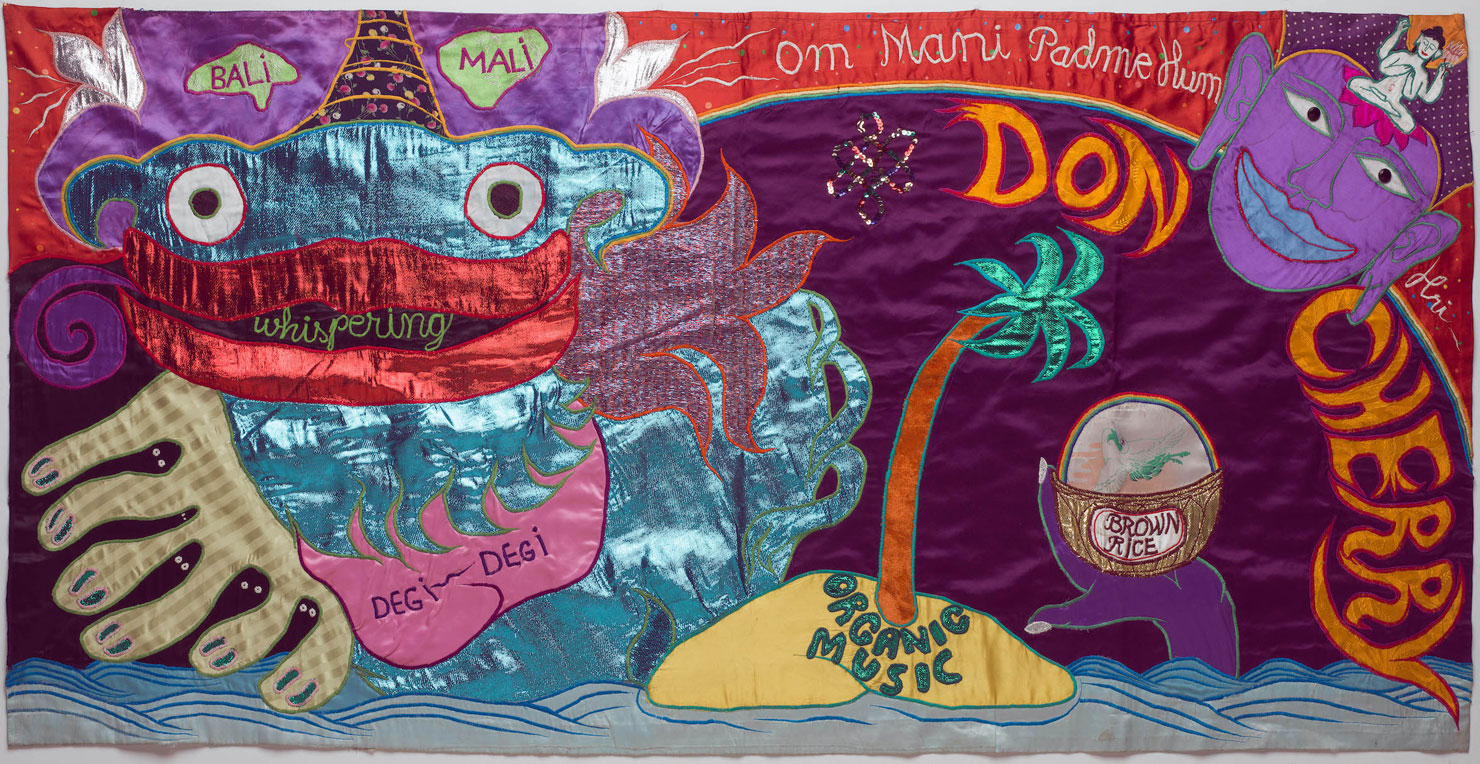

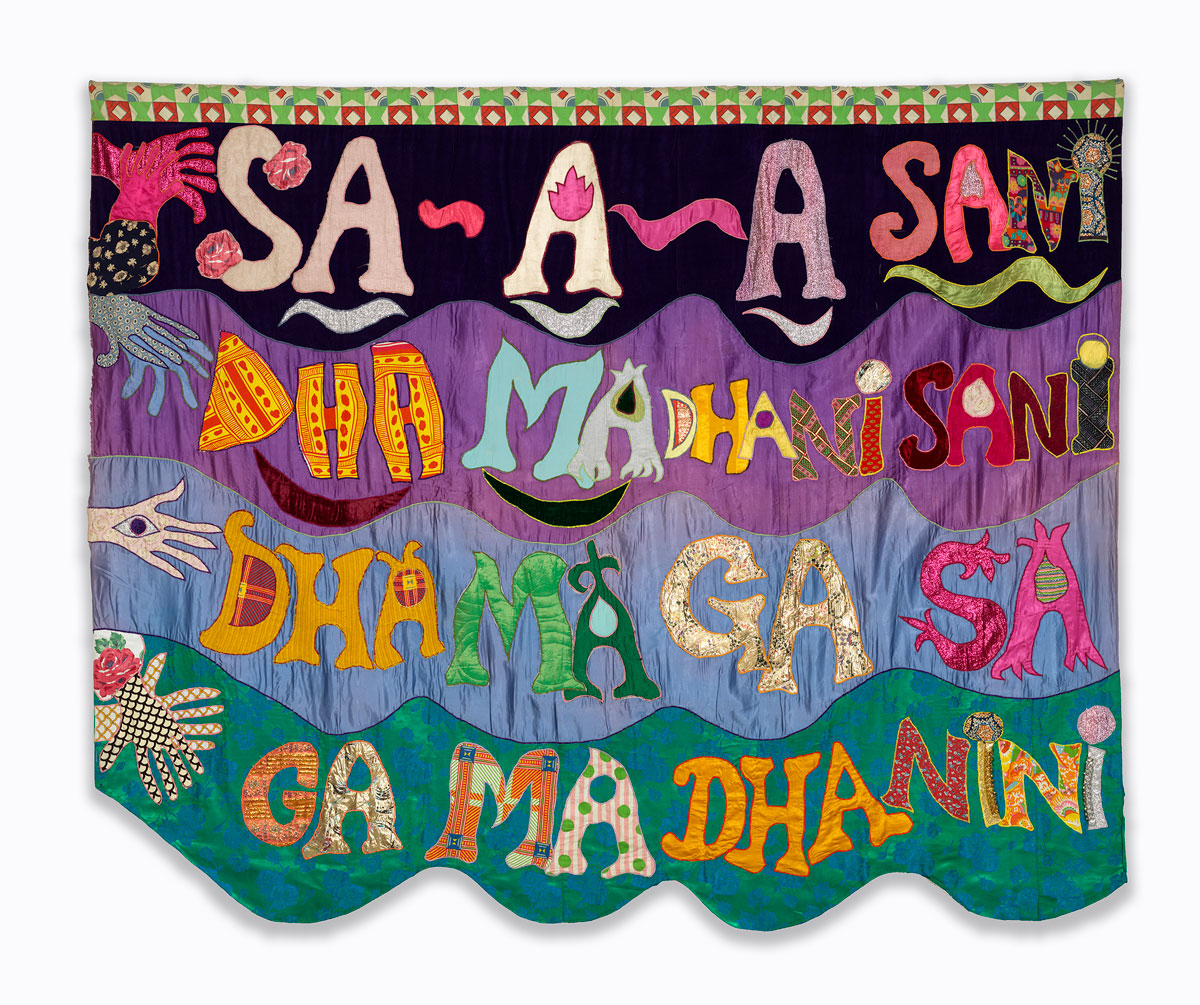

Moki Cherry’s colorful art unites painting, sculpture, textiles, and scenography. Everyday life and art are linked together; a musical instrument case forms the base for a painting, bags for packing are reworked into textile collages, and a philosophy with nature at the center is formulated in drawings. Moki Cherry herself commented on this transgressive approach with the description “the stage is a home, and the home is a stage.” The exhibition “A Journey Eternal” is the largest presentation to date of the artist’s works. Her art could be included as an element of concerts in Paris, Copenhagen, or the Scanian countryside. By presenting her art outside of art galleries and theater stages, in places such as her own home, Moki Cherry dissolved hierarchies between public and private and between creator and viewer. Children, her own and others’, were both observers and collaborators. Several of the works in the exhibition, among them “Malkauns Raga” (1973), “Dina Kanagina” (1972) and “Aum Expression” (1971), were used as scenography for concerts such as the Newport Jazz Festival, 1973. In the documentation from a concert at Moderna Museet in Stockholm 1977, the large textile “Dragon” (1975) can be seen. As mobile works, these, along with other pieces in the exhibition, could be placed in various contexts based on improvisation in the moment–concerts, exhibitions, workshops. In her art, Moki Cherry was an inquisitive researcher. She experimented with materials like plywood and clay, then returning to or working in tandem with textile applications, collage, and painting. The stylized representational and playful motifs from the 1960s and 1970s gain a new expression in the 1990s in paintings with acrylic on panels or cardboard, a practice that continued for the rest of her life. Angular forms become labyrinthine landscapes with spacelike creatures and in abstract works, the forms are brought together in compositions with bold colour combinations. Several of the abstract paintings are designed as diptychs, with one picture picking up where the other ends. Sometimes, a representational element appears, gear wheels and veins lead the thoughts toward mechanics as well as bodies. In her notes, Moki Cherry writes about how she begins working with bow saws in the 1970s, abandons it, but takes it up again with new, better tools in the 1980s. She saws out peaceful figures such as “Buddha” (1998) or expressive faces in plywood and constructs sculptural, wall-mounted lamps. At Greenwich House Pottery in New York in the 1990s, she begins creating ceramics. She makes dogs and winged goats, some with bodies shaped as dishes and utilitarian objects. Along her vases and across bowls, snakes entwine, a motif she constantly returned to and where the snake biting its own tail symbolizes eternal cycles and for Moki it was a way to depict time. She gained inspiration from ancient ceramic traditions and many other cultures, but it is also possible to see a kinship with contemporary art colleagues such as her friend Niki de Saint Phalle and Ulrica Hydman Vallien’s 1960s ceramics.

In the 2000s in New York, Moki Cherry immersed herself in creative writing for the feminist art historian Arlene Raven. Regardless of whether it was a sentence on a bowl or a longer poem, writing was always an active part of her artistic practice. In the home, Moki covered furniture – desks, chairs, and bookshelves – with newspaper photos and created three-dimensional collages that became a part of the decor. From 2003 on, she dedicated herself to two-dimensional collage – more austere, sensual with surrealist combinations, as in “Let it Flow” (2006), which combines oysters, orchids, twisted forms and folded fabrics. By bringing together pictures she had collected, she continued in her characteristic way to blend the personal and the political, humor and war, and women’s rights and fantasy. In 2007, she wrote: “On my second birthday, my mother gave me a very sharp pair of scissors. It’s interesting to arrive at something so familiar – scissors and paper – after a lot of life and experience. It might look back at you”. In the exhibition, there is a creative workshop which is a natural extension of the self-evident inclusion of children in the creative context created in Tågarp and other projects. In the 1970s, new art was asking for a new society. The boundary between private and public was fluid, and at concerts, hierarchies between musicians and audience were dissolved, and viewers became participants. Between 1978 and 1986, for nine summers, Moki Cherry and Anita Roney were central for the children’s theater Octopuss’ performances. They made costumes, scenography and organization for the teenagers’ self-written and self-directed performances, which were created over five to six weeks. The premiere took place in Tågarp and then they toured and often finished at Moderna Museet in Stockholm. The 1970s in Sweden are associated with original and experimental children’s programs, which was partly a result of Swedish Television had created a children’s program board in 1969; children’s programming thus had status. In 1971 the children’s program Piff, Paff, Puff was recorded in Tågarp (broadcast in 1972), and in the same year, Elefantasi with the main character Fantasimon was created for Swedish Radio with the Cherrys. Loosely connected, the programs encourage creativity – play, music, and stories create the action, and the children participate.

Photo: Moki Cherry, Title Unknown, c. 1970, © Tom Van Eynde, Corbett vs Dempsey Bildupphovsrätt 2023

Info: Curators: Elisabeth Millqvist and Andreas Nilsson, Moderna Museet, Ola Billgrens plats 2–4, Malmö, Sweden, Duration: 23/9/2023-3/3/2024, Days & Hours: Tue-Wed & Fri-Sun 11:00-17:00, Fri 11:00-19:00, www.modernamuseet.se/

Right: Moki Cherry, Title Unknown, 1968, © Cherry Archive, Estate of Moki Cherry Bildupphovsrätt 2023

Right: Moki cherry in musical workshop at school, 1973, © Cherry Archive, Estate of Moki Cherry Bildupphovsrätt 2023