ART CITIES: N.York-Kenneth Noland

As a member of the Color Field contingent that practiced hard-edge abstraction, Kenneth Noland was interested in removing all emotional content from his paintings. He even executed some works on shaped canvases that were filled by their compositions from edge to edge, leaving no marginal space for suggestions of depth or background. In these shaped works, the viewer no longer looks “into” the picture; instead, the work of art coexists in the viewer’s space as a complete object.

As a member of the Color Field contingent that practiced hard-edge abstraction, Kenneth Noland was interested in removing all emotional content from his paintings. He even executed some works on shaped canvases that were filled by their compositions from edge to edge, leaving no marginal space for suggestions of depth or background. In these shaped works, the viewer no longer looks “into” the picture; instead, the work of art coexists in the viewer’s space as a complete object.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Pace Gallery Archive

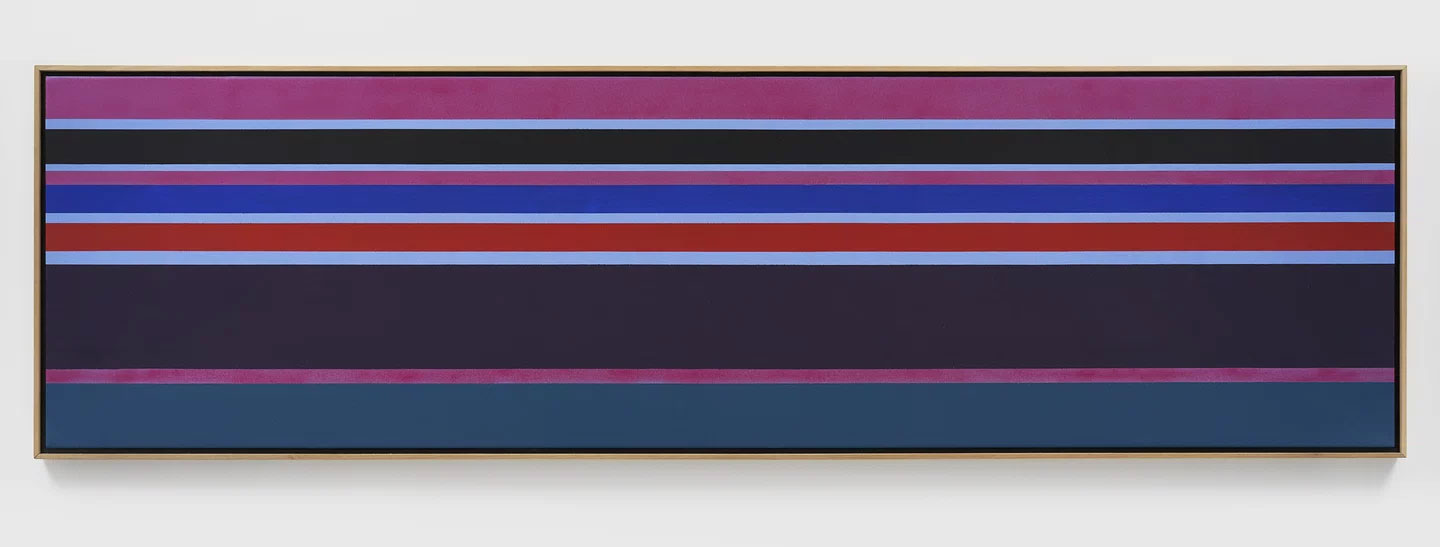

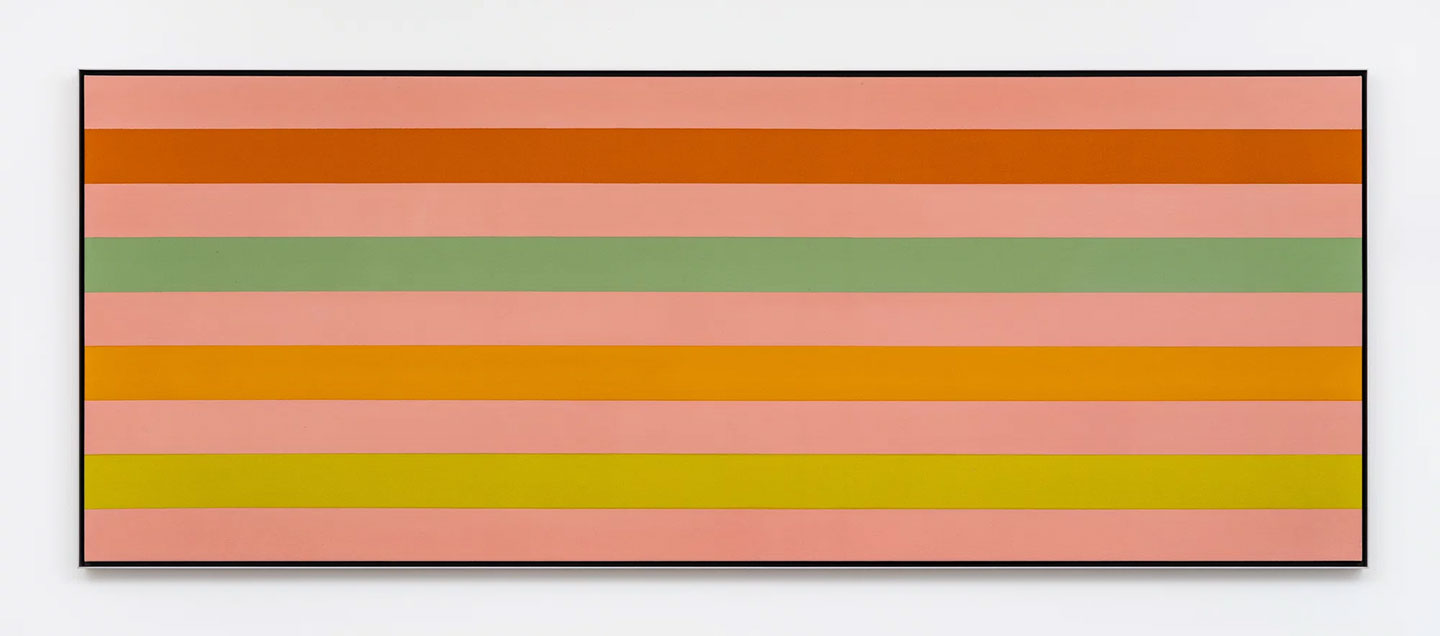

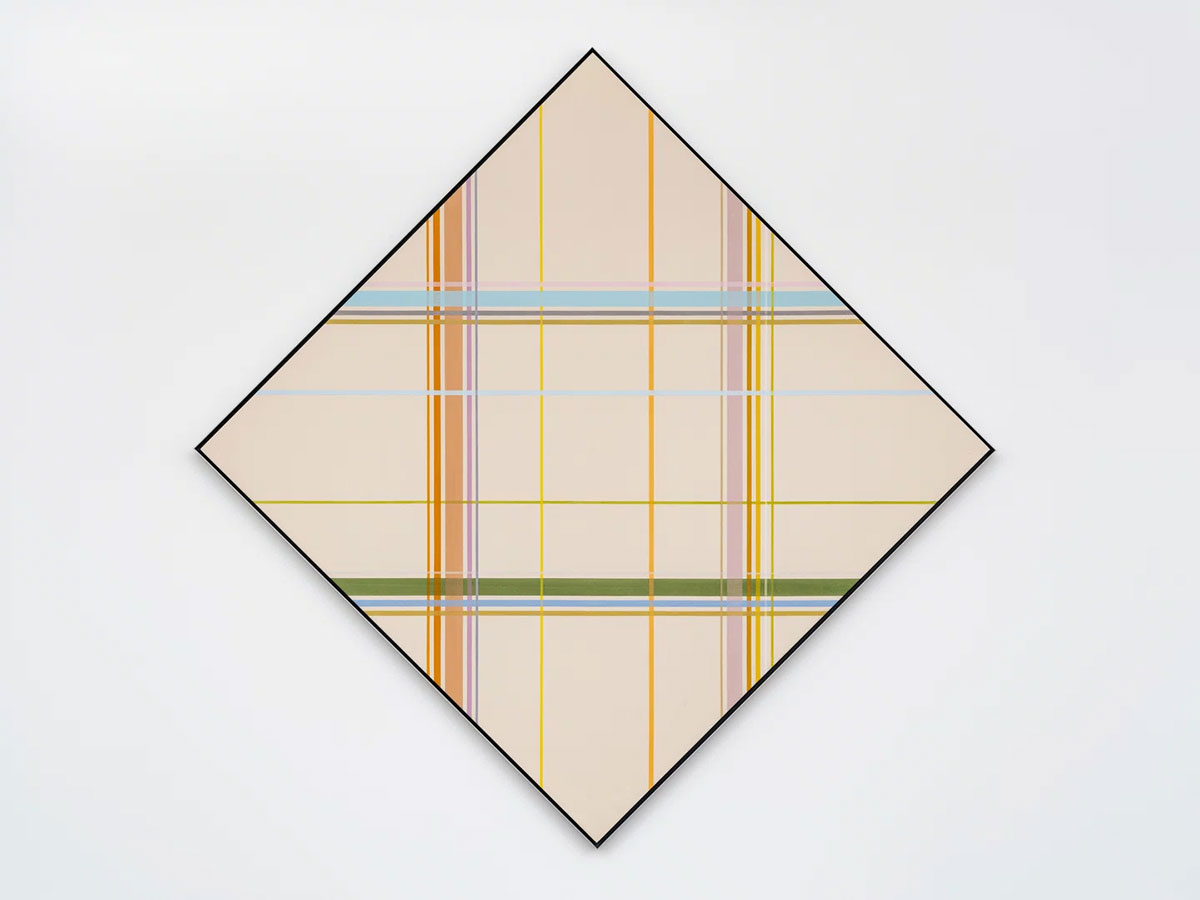

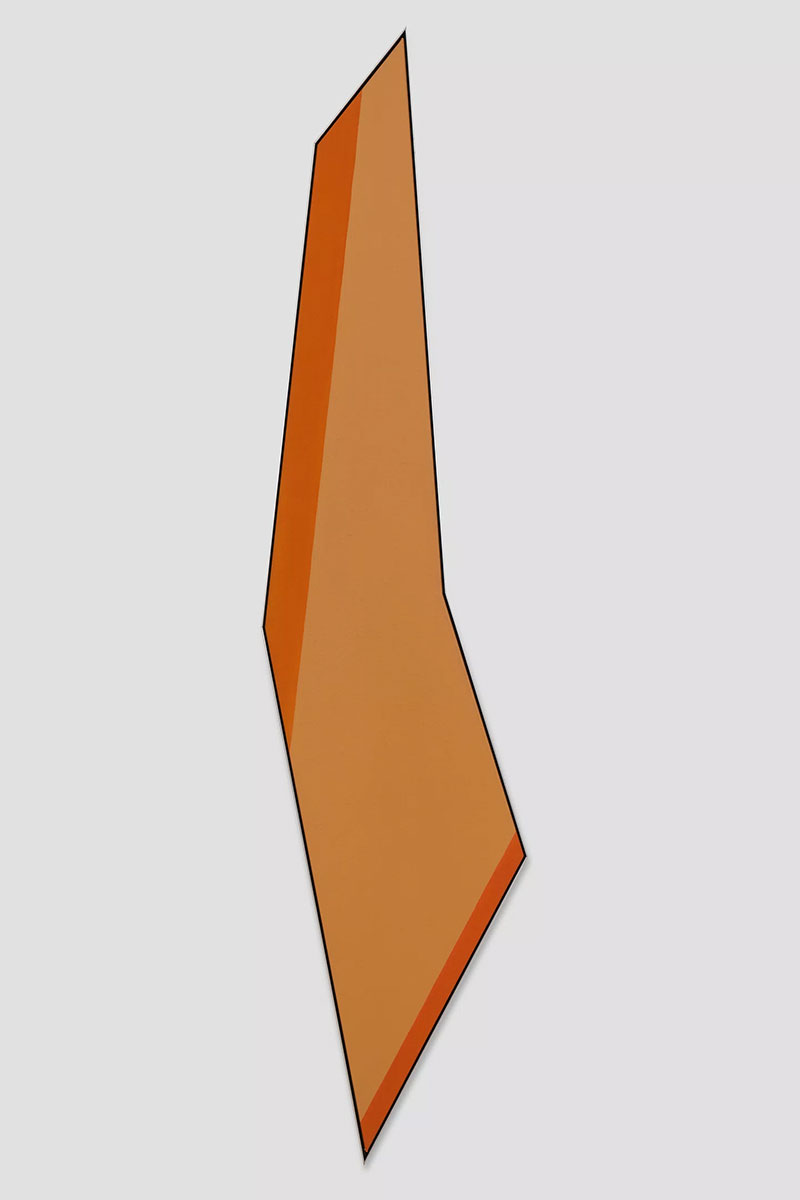

A founding member of the Washington Color School, which included Sam Gilliam, Morris Louis, and Alma Thomas, Kenneth Noland was instrumental in forging the language of post-war abstraction in the US. His experimental approach to form, material, and color gave rise to radical works that redefined the medium of painting. Between 1946 and 1948, Noland studied at Black Mountain College in his native North Carolina. There, he was exposed to the ideas of seminal figures such as Josef Albers and John Cage, developing an early interest in the expressive potential of color and chance. As his style matured, the artist would continue to treat color as resonant force in his abstractions, which feature circles, chevrons, and other geometric forms. The exhibition “Stripes/Plaids/Shapes” presents early examples of Kenneth Noland’s striped works from the late 1960s. The artist’s horizontally oriented paintings from this period stretch across several meters beyond the viewer’s peripheral vision, evoking the feel of a vast, enveloping landscape. Noland would use an array of techniques to apply bands of color in specific proportions, including staining the raw canvas or using a traditional paint roller, to create textural variation. With his use of acrylic paint, which cannot be reworked as easily as oil, Noland embraced the risk factor, quipping that he was a “one-shot painter.” Regardless of the technique he employed in his painting practice, Noland intentionally removed traces of his hand to focus attention on the materiality of the works while also allowing for chance reactions where bands of paint meet. Following his poured circle paintings of the late 1950s, Noland’s paintings of the 1960s can be understood in radical opposition to the gestural, painterly canvases of the Abstract Expressionists. At the start of the 1970s, Noland began painting vertical stripes over his horizontal bands. The resulting works, his “Plaid” paintings, draw parallels with the paintings of Piet Mondrian, an early influence on Noland via his Black Mountain College teacher Ilya Bolotowsky, a proponent of the De Stijl philosophy. But unlike Mondrian, Noland retained the soft blur of stained canvas in his lines, cultivating a quasi-alchemical effect as colors overlap and knit together. In “Interface” (1973), striking lines of warm yellow, orange, green, red, and sky blue interweave across the diamond shaped canvas, inviting viewers to closely examine the interaction of color, form, and mark. In the ensuing years, Noland continued his experimentation by turning his attention to the canvas support itself. By creating shaped paintings that took unusual, asymmetrical forms, Noland emphasized the objecthood of the painting. In “Glean” (1977) the picture plane is stained with earth-toned hues of green while borders of brightly colored stripes are positioned opposite one another, creating a spatial tension in the composition. These works, with their large expanses of a single color, have a textural richness resulting from the paint’s interaction with the raw canvas and the artist’s distinct and often uneven application. In the ensuing years, Noland continued his experimentation by turning his attention to the canvas support itself. By creating shaped paintings that took unusual, asymmetrical forms, Noland emphasized the objecthood of the painting. These works, with their large expanses of a single color, have a textural richness resulting from the paint’s interaction with the raw canvas and the artist’s distinct and often uneven application.

Photo: Kenneth Noland, Glean, 1977, acrylic on canvas, 93″ × 76-1/2″ (236.2 cm × 194.3 cm), © The Kenneth Noland Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Courtesy Pace Gallery

Info: Pace Gallery, 540 West 25th Street, New York, NY, USA, Duration: 17/3-29/4/2023, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, www.pacegallery.com/