TRACES: Kara Walker

Today is the occasion to bear in mind one of the most complex and prolific American artists of her generation. Kara Walker (26/11/1969- ) has gained national and international recognition for her cut-paper silhouettes depicting historical narratives haunted by sexuality, violence, and subjugation. she has also used drawing, painting, text, shadow puppetry, film and sculpture to expose the ongoing psychological injury caused by the tragic legacy of slavery. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind one of the most complex and prolific American artists of her generation. Kara Walker (26/11/1969- ) has gained national and international recognition for her cut-paper silhouettes depicting historical narratives haunted by sexuality, violence, and subjugation. she has also used drawing, painting, text, shadow puppetry, film and sculpture to expose the ongoing psychological injury caused by the tragic legacy of slavery. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

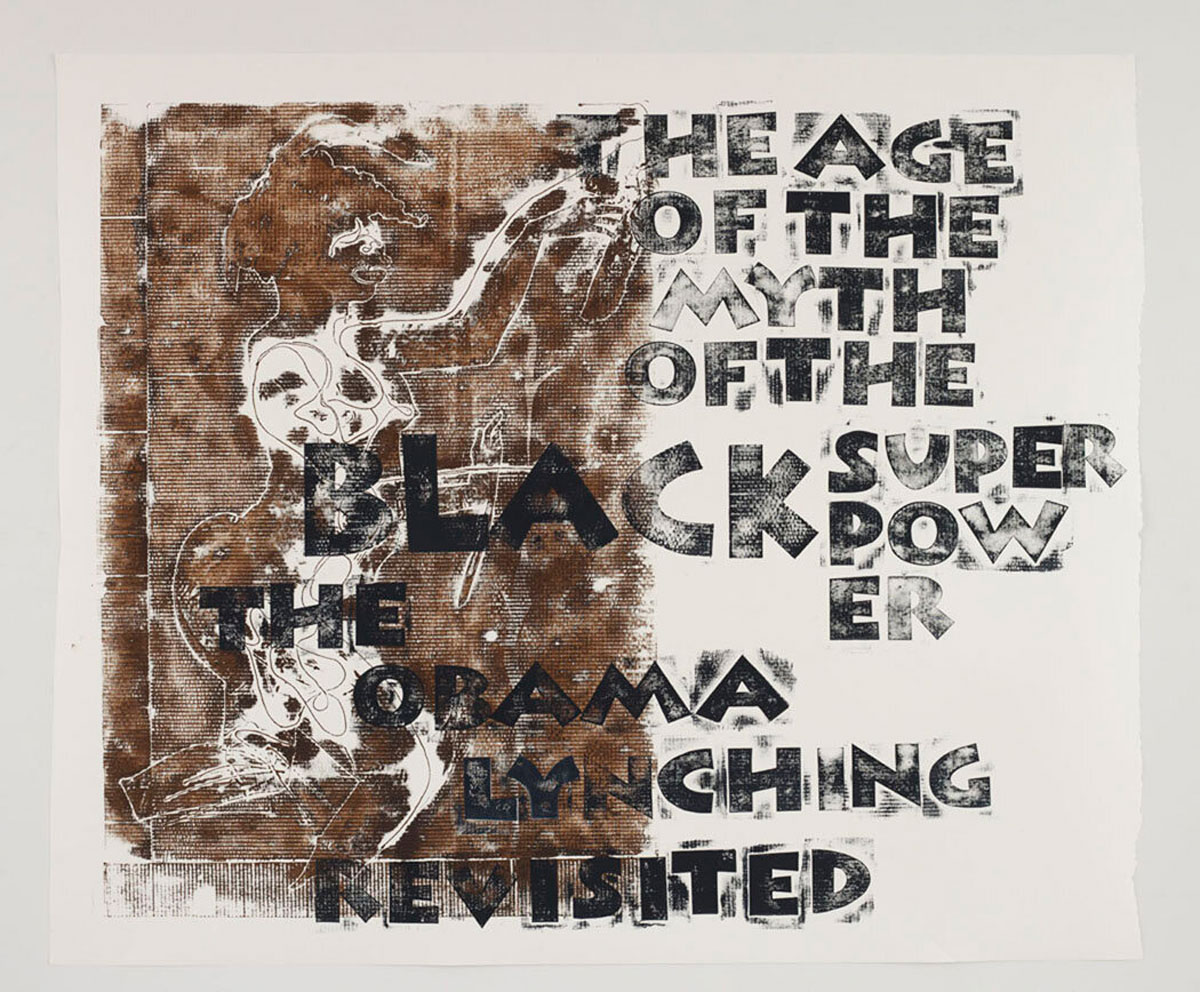

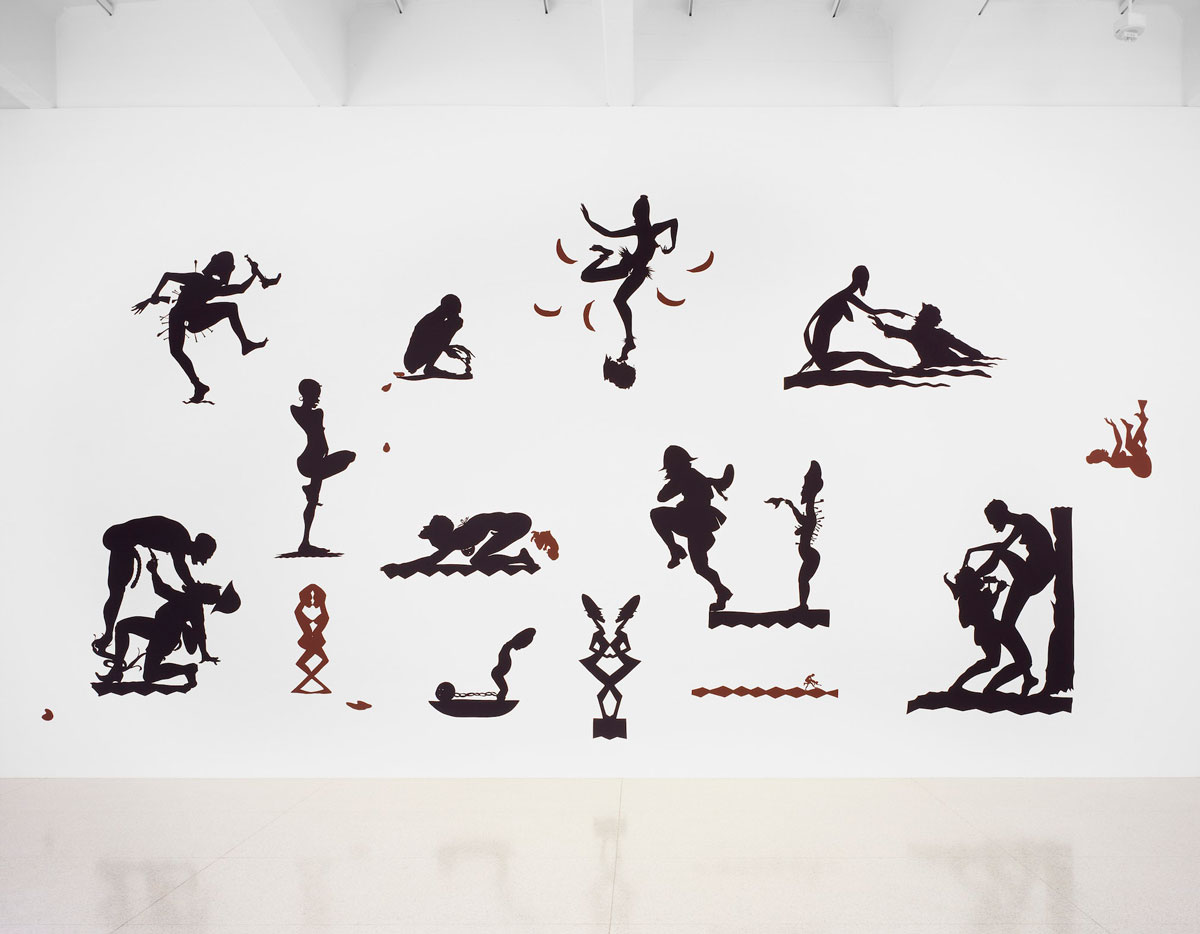

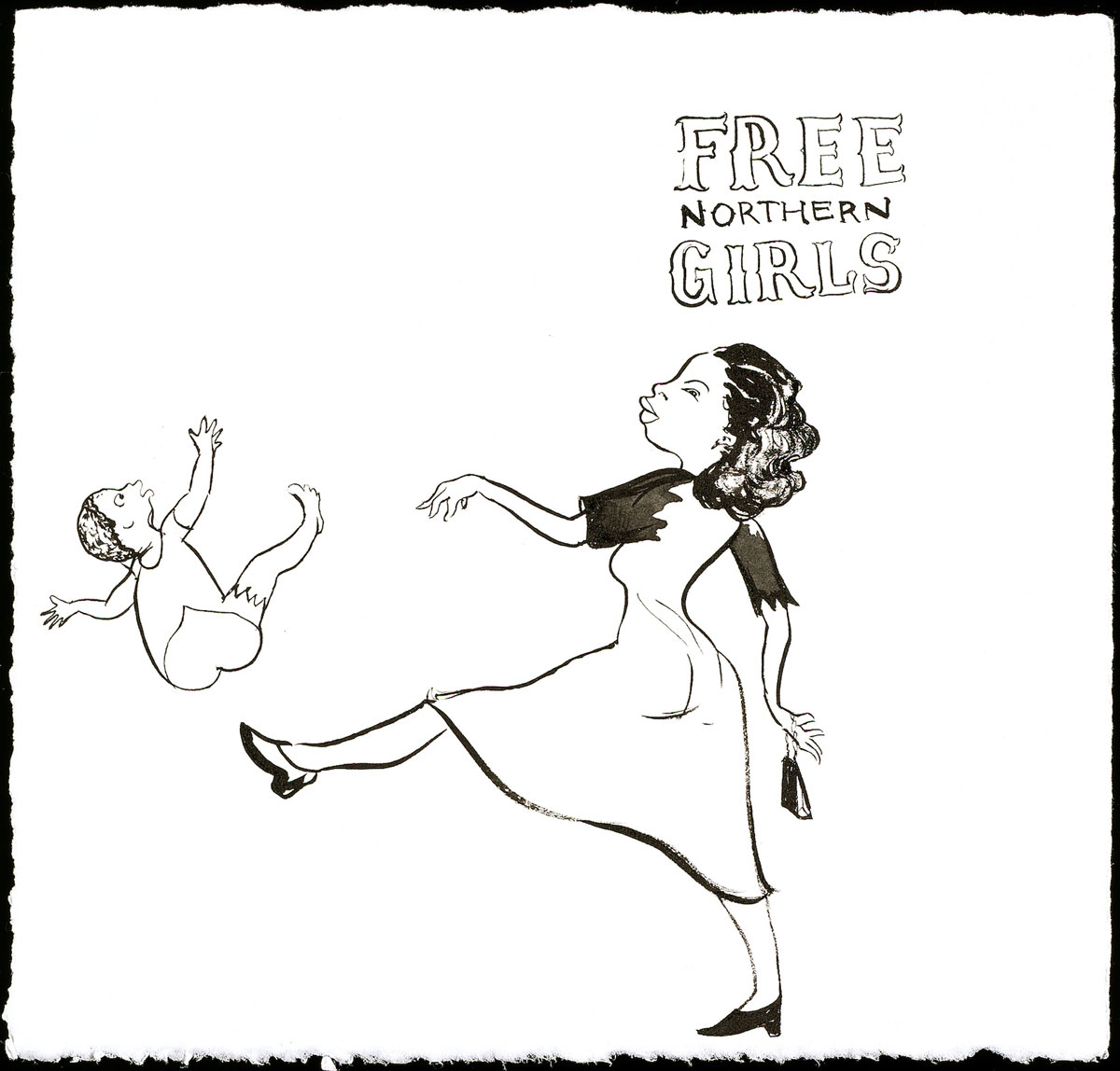

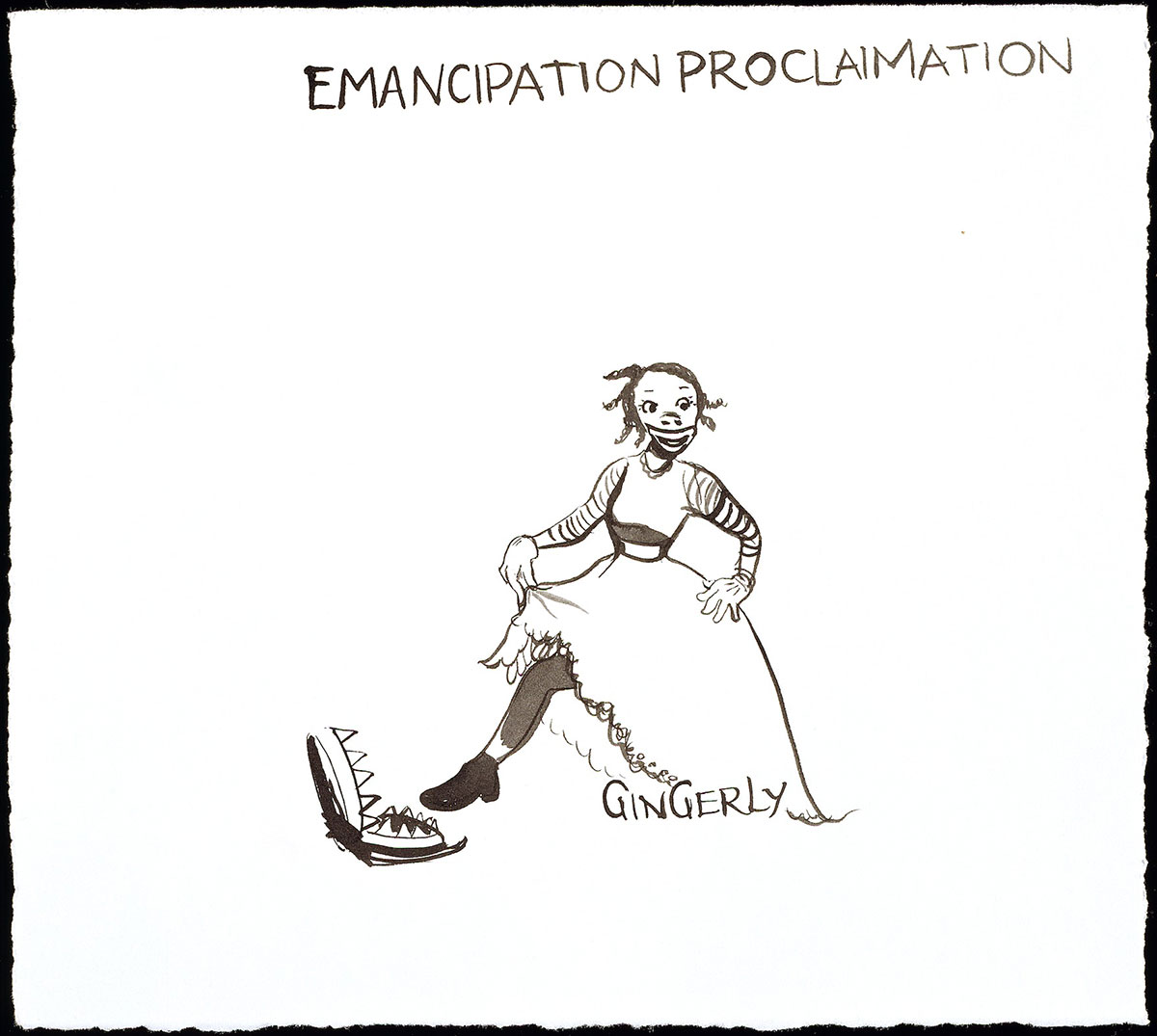

Kara Walker was born into a family of academics in Stockton, California in 1969. When her father accepted a position at Georgia State University, she moved with her parents to Stone Mountain, Georgia, at the age of 13. In contrast with the widespread multi-cultural environment Walker had enjoyed in coastal California, Stone Mountain still held Klu Klux Klan rallies. At her new high school, Walker recalls, “I was called a ‘nigger’ told I looked like a monkey, accused of being a Yankee”. Walker felt unwelcome, isolated, and expected to conform to a stereotype in a culture that did not seem to fit her. Walker attended the Atlanta College of Art with an interest in painting and printmaking, and in response to pressure and expectation from her instructors Walker focused on race-specific issues. She then attended graduate school at the Rhode Island School of Design, where her work expanded to include sexual as well as racial themes based on portrayals of African Americans in art, literature, and historical narratives. She began to draw on a diverse array of sources from the portrait to the pornographic novel that have continued to shape her work. Other artists who addressed racial stereotypes were also important role models for the emerging artist. While still in graduate school, Walker alighted on an old form that would become the basis for her strongest early work. Widespread in Victorian middle-class portraiture and illustration, cut paper silhouettes possessed a streamlined elegance that, as Walker put it, “simplified the frenzy I was working myself into.” Walker’s first installation bore the epic title “Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart” (1994), and was a critical success that led to representation with Wooster Gardens Gallery. Its caricatured antebellum figures, which are engaged in violent and sexual interactions, were silhouettes cut from black paper and installed directly on the wall. The silhouette technique has its roots in the sentimental Victorian “ladies’ art” of shadow portraits, but the scale of Walker’s work also alluded to the 360-degree historical cycloramas popular during the post-Civil War era for the depiction of battle scenes. Walker has continued to use both the silhouette and cyclorama forms to explore the nature of race representation as well as the history of figuration and narrative in contemporary art. In Endless Conundrum, an African American Anonymous Adventuress (2001), she interrogates the representation of the black body by Modernist artists from Matisse to Brancusi. A series of subsequent solo exhibitions solidified her success, and in 1998 she received the MacArthur Foundation Achievement Award. Despite a steady stream of success and accolades, Walker faced considerable opposition to her use of the racial stereotype. Among the most outspoken critics of Walker’s work was Betye Saar, the artist famous for arming Aunt Jemima with a rifle in “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” (1972), one of the most effective, iconic uses of racial stereotype in 20th-century art. Nonetheless, Saar insisted Walker had gone too far, and spearheaded a campaign questioning Walker’s employment of racist images in an open letter to the art world asking: “Are African Americans being betrayed under the guise of art?” Walker’s series of watercolors entitled “Negress Notes” (Brown Follies, 1996-97) was sharply criticized in a slew of negative reviews objecting to the brutal and sexually graphic content of her images. Saar and other critics expressed concern that the work did little more than perpetuate negative stereotypes, setting the clock back on representations of race in America. Others defended her, applauding Walker’s willingness to expose the ridiculousness of these stereotypes, “turning them upside down, spread-eagle and inside out” as political activist and Conceptual artist Barbara Kruger put it. Also in December 2012, the Newark Library in New Jersey covered up a large Walker drawing, part of which depicted a white man holding the head of a naked Black women to his groin, after employees and patrons complained about the work. Library officials later uncovered the drawing, allowing it to be shown. Walker, still in mid-career, continues to work steadily. Despite ongoing star status since her twenties, she has kept a low profile. In 1996 she married (and subsequently divorced) German-born jewelry designer and RISD professor Klaus Burgel, with whom she had a daughter, Octavia. Interviews with Walker over the years reveal the care and exacting precision with which she plans each project. They also radiate a personal warmth and wit one wouldn’t necessarily expect, given the weighty content of her work. When an interviewer asked her in 2007 if she had had any experience with children seeing her work, Walker responded “just my daughter… she did at age four say something along the lines of ‘Mommy makes mean art.'” Walker has continued to use both the silhouette and cyclorama forms to explore the nature of race representation as well as the history of figuration and narrative in contemporary art. In “Endless Conundrum, an African American Anonymous Adventuress” (2001), she interrogates the representation of the black body by Modernist artists from Matisse to Brancusi. In the early 2000s, Walker began making 16mm films and video installations that set her silhouettes in motion. “Testimony: Narrative of a Negress Burdened by Good Intentions” (2004) is a short, silent 16mm film in a lurid story of masters and slaves is told with shadow puppets and title cards. In the 5-screen video installation “…calling to me from the angry surface of some grey and threatening sea, I was transported” (2007), Walker set her black shadow puppets against intensely colored backgrounds and added a soundtrack of music by a Southern country band. The work references both the history of slavery in America and contemporary events such as the 2003 genocide in Darfur, Sudan, reminding viewers that images of black bodies in pain continue to be a European/American spectacle. In 2014, Walker produced her first site-specific sculpture, “A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby”, which was installed in a warehouse in a former Domino Sugar compound in Brooklyn. The centerpiece was a monumental Sphinxlike woman with caricatured features and an Aunt Jemima kerchief, which Walker fashioned from blocks of polystyrene coated with white sugar, which was attended by thirteen molasses-colored boys made of either cast sugar or resin. Both witty and unsettling, the work reminds us that refined sugar, a luxury once used to make the table decorations known as subtleties, was harvested by slaves on Caribbean sugar cane plantations.

Kara Walker was born into a family of academics in Stockton, California in 1969. When her father accepted a position at Georgia State University, she moved with her parents to Stone Mountain, Georgia, at the age of 13. In contrast with the widespread multi-cultural environment Walker had enjoyed in coastal California, Stone Mountain still held Klu Klux Klan rallies. At her new high school, Walker recalls, “I was called a ‘nigger’ told I looked like a monkey, accused of being a Yankee”. Walker felt unwelcome, isolated, and expected to conform to a stereotype in a culture that did not seem to fit her. Walker attended the Atlanta College of Art with an interest in painting and printmaking, and in response to pressure and expectation from her instructors Walker focused on race-specific issues. She then attended graduate school at the Rhode Island School of Design, where her work expanded to include sexual as well as racial themes based on portrayals of African Americans in art, literature, and historical narratives. She began to draw on a diverse array of sources from the portrait to the pornographic novel that have continued to shape her work. Other artists who addressed racial stereotypes were also important role models for the emerging artist. While still in graduate school, Walker alighted on an old form that would become the basis for her strongest early work. Widespread in Victorian middle-class portraiture and illustration, cut paper silhouettes possessed a streamlined elegance that, as Walker put it, “simplified the frenzy I was working myself into.” Walker’s first installation bore the epic title “Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart” (1994), and was a critical success that led to representation with Wooster Gardens Gallery. Its caricatured antebellum figures, which are engaged in violent and sexual interactions, were silhouettes cut from black paper and installed directly on the wall. The silhouette technique has its roots in the sentimental Victorian “ladies’ art” of shadow portraits, but the scale of Walker’s work also alluded to the 360-degree historical cycloramas popular during the post-Civil War era for the depiction of battle scenes. Walker has continued to use both the silhouette and cyclorama forms to explore the nature of race representation as well as the history of figuration and narrative in contemporary art. In Endless Conundrum, an African American Anonymous Adventuress (2001), she interrogates the representation of the black body by Modernist artists from Matisse to Brancusi. A series of subsequent solo exhibitions solidified her success, and in 1998 she received the MacArthur Foundation Achievement Award. Despite a steady stream of success and accolades, Walker faced considerable opposition to her use of the racial stereotype. Among the most outspoken critics of Walker’s work was Betye Saar, the artist famous for arming Aunt Jemima with a rifle in “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” (1972), one of the most effective, iconic uses of racial stereotype in 20th-century art. Nonetheless, Saar insisted Walker had gone too far, and spearheaded a campaign questioning Walker’s employment of racist images in an open letter to the art world asking: “Are African Americans being betrayed under the guise of art?” Walker’s series of watercolors entitled “Negress Notes” (Brown Follies, 1996-97) was sharply criticized in a slew of negative reviews objecting to the brutal and sexually graphic content of her images. Saar and other critics expressed concern that the work did little more than perpetuate negative stereotypes, setting the clock back on representations of race in America. Others defended her, applauding Walker’s willingness to expose the ridiculousness of these stereotypes, “turning them upside down, spread-eagle and inside out” as political activist and Conceptual artist Barbara Kruger put it. Also in December 2012, the Newark Library in New Jersey covered up a large Walker drawing, part of which depicted a white man holding the head of a naked Black women to his groin, after employees and patrons complained about the work. Library officials later uncovered the drawing, allowing it to be shown. Walker, still in mid-career, continues to work steadily. Despite ongoing star status since her twenties, she has kept a low profile. In 1996 she married (and subsequently divorced) German-born jewelry designer and RISD professor Klaus Burgel, with whom she had a daughter, Octavia. Interviews with Walker over the years reveal the care and exacting precision with which she plans each project. They also radiate a personal warmth and wit one wouldn’t necessarily expect, given the weighty content of her work. When an interviewer asked her in 2007 if she had had any experience with children seeing her work, Walker responded “just my daughter… she did at age four say something along the lines of ‘Mommy makes mean art.'” Walker has continued to use both the silhouette and cyclorama forms to explore the nature of race representation as well as the history of figuration and narrative in contemporary art. In “Endless Conundrum, an African American Anonymous Adventuress” (2001), she interrogates the representation of the black body by Modernist artists from Matisse to Brancusi. In the early 2000s, Walker began making 16mm films and video installations that set her silhouettes in motion. “Testimony: Narrative of a Negress Burdened by Good Intentions” (2004) is a short, silent 16mm film in a lurid story of masters and slaves is told with shadow puppets and title cards. In the 5-screen video installation “…calling to me from the angry surface of some grey and threatening sea, I was transported” (2007), Walker set her black shadow puppets against intensely colored backgrounds and added a soundtrack of music by a Southern country band. The work references both the history of slavery in America and contemporary events such as the 2003 genocide in Darfur, Sudan, reminding viewers that images of black bodies in pain continue to be a European/American spectacle. In 2014, Walker produced her first site-specific sculpture, “A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby”, which was installed in a warehouse in a former Domino Sugar compound in Brooklyn. The centerpiece was a monumental Sphinxlike woman with caricatured features and an Aunt Jemima kerchief, which Walker fashioned from blocks of polystyrene coated with white sugar, which was attended by thirteen molasses-colored boys made of either cast sugar or resin. Both witty and unsettling, the work reminds us that refined sugar, a luxury once used to make the table decorations known as subtleties, was harvested by slaves on Caribbean sugar cane plantations.