PRESENTATION: Sam Gilliam, White and Black Paintings 1975–1977

Sam GilliamSam Gilliam is associated with the Washington Color School, a group of Washington, D.C. area artists that developed a form of abstract art from color field painting in the 1950s and 1960s. His works have also been described as belonging to abstract expressionism and lyrical abstraction. He works on stretched, draped and wrapped canvas, and adds sculptural 3D elements. He is recognized as the first artist to introduce the idea of a draped, painted canvas hanging without stretcher bars around 1965. This was a major contribution to the Color Field School.

Sam GilliamSam Gilliam is associated with the Washington Color School, a group of Washington, D.C. area artists that developed a form of abstract art from color field painting in the 1950s and 1960s. His works have also been described as belonging to abstract expressionism and lyrical abstraction. He works on stretched, draped and wrapped canvas, and adds sculptural 3D elements. He is recognized as the first artist to introduce the idea of a draped, painted canvas hanging without stretcher bars around 1965. This was a major contribution to the Color Field School.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: David Kordansky Gallery Archive

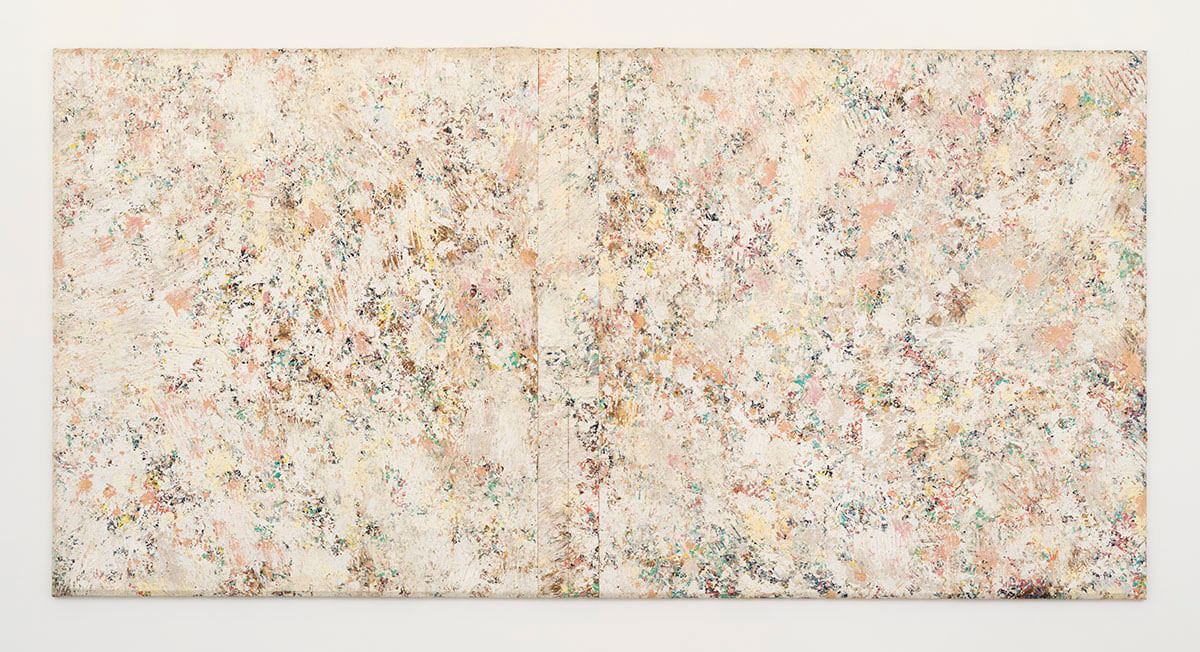

The exhibition “White and Black Paintings, 1975–1977” brings together important works from a period when Sam Gilliam experimented with color, texture, scale, and materiality in wholly new ways. Beginning with the “White” paintings, Gilliam built up sculptural, all-over surfaces dominated by layers of white paint made viscerally frenetic through the incorporation of hardening mediums that give them a palpable presence. Other colors that emerge from behind and around these encrusted white veils engage in a limitless play of dark and light, introducing complex, shifting moods in these decidedly non-monochromatic images. He also continued his use of beveled-edge stretchers; previous beveled-edge works foregrounded juxtapositions of prismatic color and dynamic sculptural form. In the White and Black paintings, the stretchers further emphasize the architectural solidity of Gilliam’s approach to pigment and medium, and firmly root the works in the spaces where they are installed. Perhaps most unexpectedly, Gilliam also experimented with collage by applying strips of painted canvas to each work’s primary canvas substrate, creating instances of disruption and camouflage with graphic and physical resonance alike. In the monumental, fifteen-foot-wide “Double River” (1976), for instance, a vertically oriented strip of collaged canvas creates a barely-off-center zip that not only generates optical movement, but also provides an abstract stand-in for the viewer and a process of scanning the painting that takes place in the eye and the body. This is the kind of development that could only occur in the work of an artist who had engaged with radical experiments in three-dimensional space. Each of the processes Gilliam brought to Double River” exemplifies his ongoing engagement with issues of dimensionality, flatness, and motion, and serves as a reminder that, in addition to reformulating the contexts in which paintings were seen, he was dedicated to reformulating how they were made. In the “White” paintings and the “Black” paintings that would immediately follow this dedication meant trying out new materials as well as applying them in different ways. The works are characterized by marks made with everyday tools; among them are shag rug rakes that Gilliam first employed during this period and continued to use in subsequent bodies of work throughout the next five decades. The rake allowed him to introduce both energetic linearity and textural relief and, as seen especially in the Black paintings, highlight the geological feel of the paints he was mixing. Through these works, Gilliam continued to envision how painting could be a fully encompassing experience, transforming the relationship between the hand and the gestural mark into one between the painter’s entire body and the complete range of their materials. “Blue Village II” (1977), whose dramatically horizontal format draws the viewer along its length, is defined by bursts of pink, green, and yellow that generate surprising spaciousness and allow its all-over scrim of black to function as both background and foreground. At its center, though, is the result of another bold use of collage: a bisected rectangular composition, imported from another work, functions as a window into a cool, vast space where triangular formsevoke infinitely receding planes. Such interventions suggest that, even as Gilliam was creating pictures carefully delimited within the confines of individual stretchers, the source of his work was a place that was larger, wilder, and more alive than anything that could be contained in a single painting. The “White” and “Black” paintings continued to provide Gilliam with inflection points throughout the remainder of his career. Many of his works from the early 2020s, for instance, found him directly expanding upon and transforming the themes that animate the paintings in this exhibition: the use of impasto; experimentation with an open array of additives; inclusion of fragments of canvas and fabric; and, perhaps most importantly, a constant commitment to the idea that, regardless of the ways in which paintings in a body of work resonate with each other, every picture presents unique challenges and opportunities for improvisation. As such, Gilliam demonstrated with these works that abstraction could not only inspire people to synthesize their thoughts and feelings about crucial issues, including race, democracy, creativity, the natural world, hat are at the core of our shared experiences as human beings, but to do so in ways that were authentic to everyone’s own experience at any given moment in time and in any given place.

Photo: Sam Gilliam, For Brass, 1976, acrylic on canvas with collage, 62 3/8 x 84 3/8 x 2 1/2 inches (158.4 x 214.3 x 6.3 cm), Collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Bernard R. Shochet, 1997

Info: David Kordansky Gallery, 5130 W. Edgewood Pl., Los Angeles, CA, USA, Duration: 5/11-17/12/2022, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, www.davidkordanskygallery.com/

Right: Sam Gilliam, Weighed Anchor, 1976, acrylic on canvas with collage, 84 1/2 x 62 1/4 x 2 1/2 inches (214.6 x 158.1 x 6.3 cm), Collection of Halley K. Harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld, New York, NY