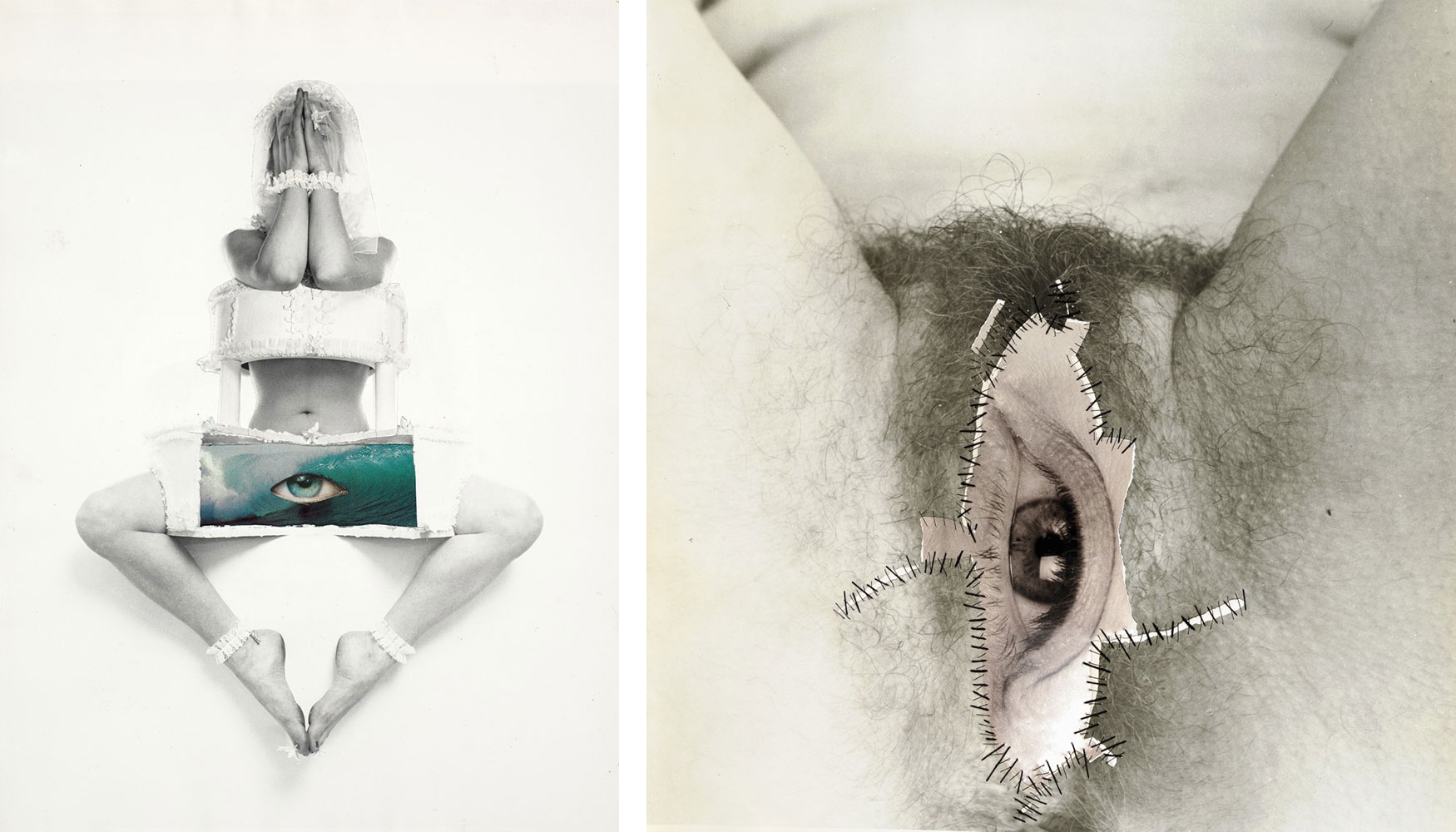

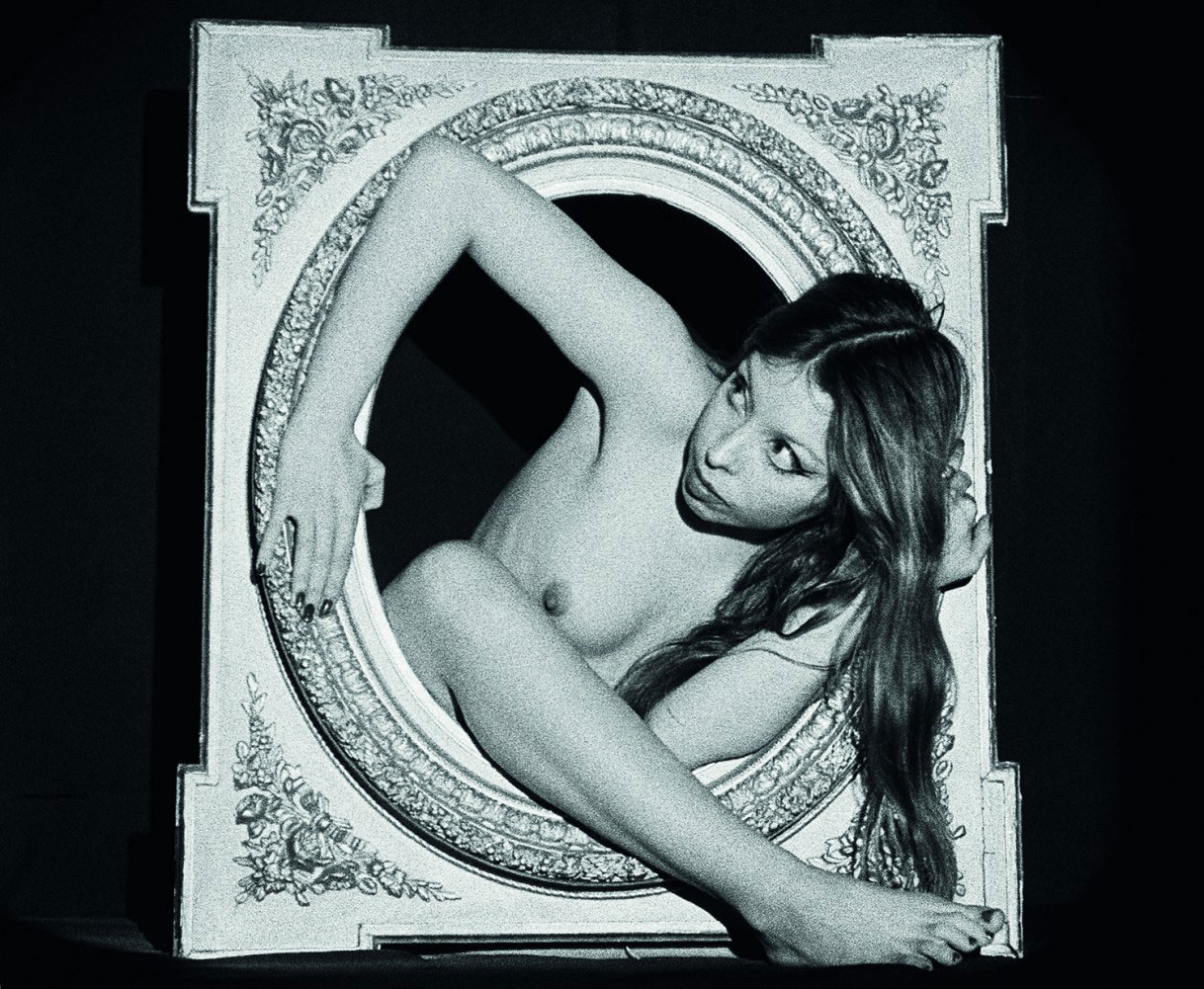

PHOTO: A Feminist Avant–Garde

In the 1970s, the female artists emancipated themselves from the role of muse and model. The stereotypical role assignments of mother, housewife and wife were radically questioned with the medium of irony. Central topics were: the discovery of female sexuality, the use of their own bodies, breaking down stereotypical images of women, the dictate of beauty and raising awareness of violence against women. The rejection of traditional, normative ideas of how a woman should live connected the commitment of the artists of this generation

In the 1970s, the female artists emancipated themselves from the role of muse and model. The stereotypical role assignments of mother, housewife and wife were radically questioned with the medium of irony. Central topics were: the discovery of female sexuality, the use of their own bodies, breaking down stereotypical images of women, the dictate of beauty and raising awareness of violence against women. The rejection of traditional, normative ideas of how a woman should live connected the commitment of the artists of this generation

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: The Rencontres d’Arles Archive

With 200 works by 71 female artists the exhibtion “A Feminist Avant-Garde: Photographs and performances from the 1970s from the Verbund Collection, Vienna”, shows a pioneering photography that was ‘too quiet and poetic’ to be properly appreciated in the 1970s. Actionist, provocative and poetic, the exhibition makes clear that the works are drawn from many different schools of feminism. Exhibitions of work from the feminist art movement often have titles like “the feminist revolution” or “radical women.” Gabriele Schor coined the term “feminist avantgarde” because of the art-historical significance of the term “avant-garde.” She explains: “For the first time in the history of art, these women artists created an entirely new ‘image of woman,’ from a female perspective. Their pioneering achievement deserves a place within the canon of art history, ensured by the term “avant-garde”. The new media of photography, film, and video were particularly useful for female artists, allowing them to break away from painting, with its male-dominated traditions. Above all, photography was a historically unencumbered medium which allowed women to work without a studio, spontaneously and without spatial constraints. The self-timer was always there if needed. The bathroom was often converted into a darkroom. The technical aspects of photography were not so much a concern for the artists of the feminist avant-garde, whose works tended to be based more on a concern for storytelling and a desire to trace narrative strands. For this reason, the exhibition is predominantly made up of series of smaller black-and-white photographs. Photography was still not widely recognized as an art medium in this period, because it allowed the same image to be reproduced multiple times, a problematic aspect for those clinging to ideas of the “unique artwork” traditionally associated with painting. At this time, Western countries saw the emergence of the second wave of the women’s movement, against a backdrop of the 1968 student movement, the “sexual revolution,” and efforts to overcome the traditional moral values of the wartime generation. Women came to see that their problems were not “personal” but instead arose from established social structures of power and dominance. Women in Western countries rebelled against legal discrimination which meant that a man, as head of a family, could single-handedly make far-reaching decisions affecting women and children. Women called for “private” issues to be discussed in public, including family law, marriage, unpaid reproductive labor, pregnancy, abortion, divorce, and violence against women.

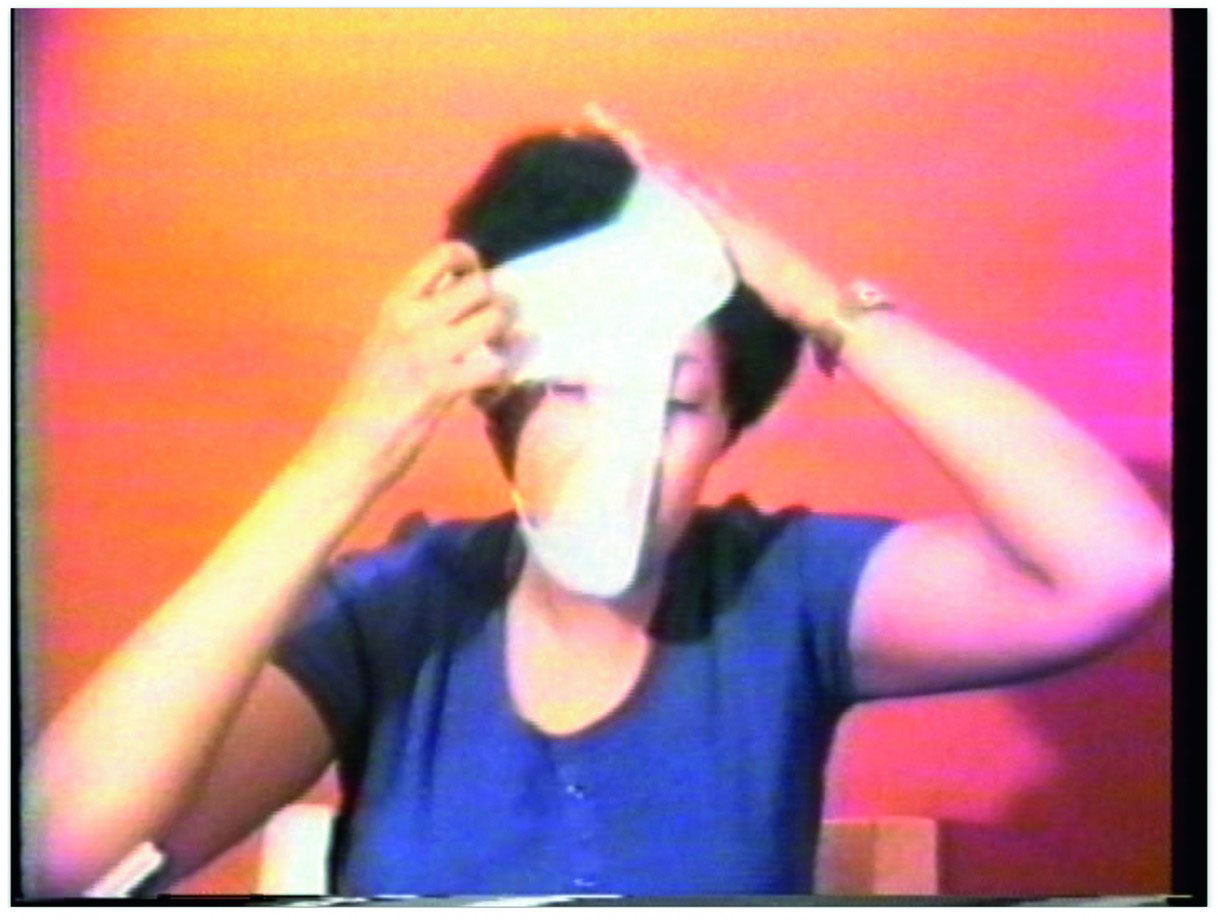

Helena Almeida’s work has always challenged traditional values in art. Her earliest work subverted classical painting through its ambiguous compositions, combining photography and other media, in which space and time, subject and object, become intertwined. Almeida experiments with her own image, seeking different ways to explore the relationship between the human body and its surrounding space. Her work “Estudo para Dois Espaços” (1977) are a series of photographs of hands clasped around metal grilles and gates. It is a response to Almeida’s own feelings of artistic isolation under Portugal’s dictatorship which cut off the country, both culturally and politically, from the rest of the world. In the series “Desenho Habitado” (1978) the artist is represented only by the shadow of a hand and pencil. Using a thread of horsehair, the series appears to show the hand pierce the surface of the photograph and then thread a real horsehair through the surface of the work, destabilising the concept of representational space. Eleanor Antin studied philosophy, writing, and theatre. She began her art career during the early 1960s as a painter, producing works informed by Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art. However in the early 1970s Antin began to experiment with performance-based works, developing an interest in how identity can be both contrived and transformative. In her video, “Representational Painting” (1971) the application of make-up becomes a transformed act of painting. At the end of the performance, Antin removes her bra – an article of clothing that was seen as unnatural and restrictive. Antin’s photograph “Portrait of the King” (1972) shows the artist with a dark beard. Head held high, this king is looking over his right shoulder, his high forehead framed by a wide-brimmed hat and long strands of hair. Her protagonist is the archetype of the nobleman – both political leader and father figure –taking paternal responsibility for his domain.

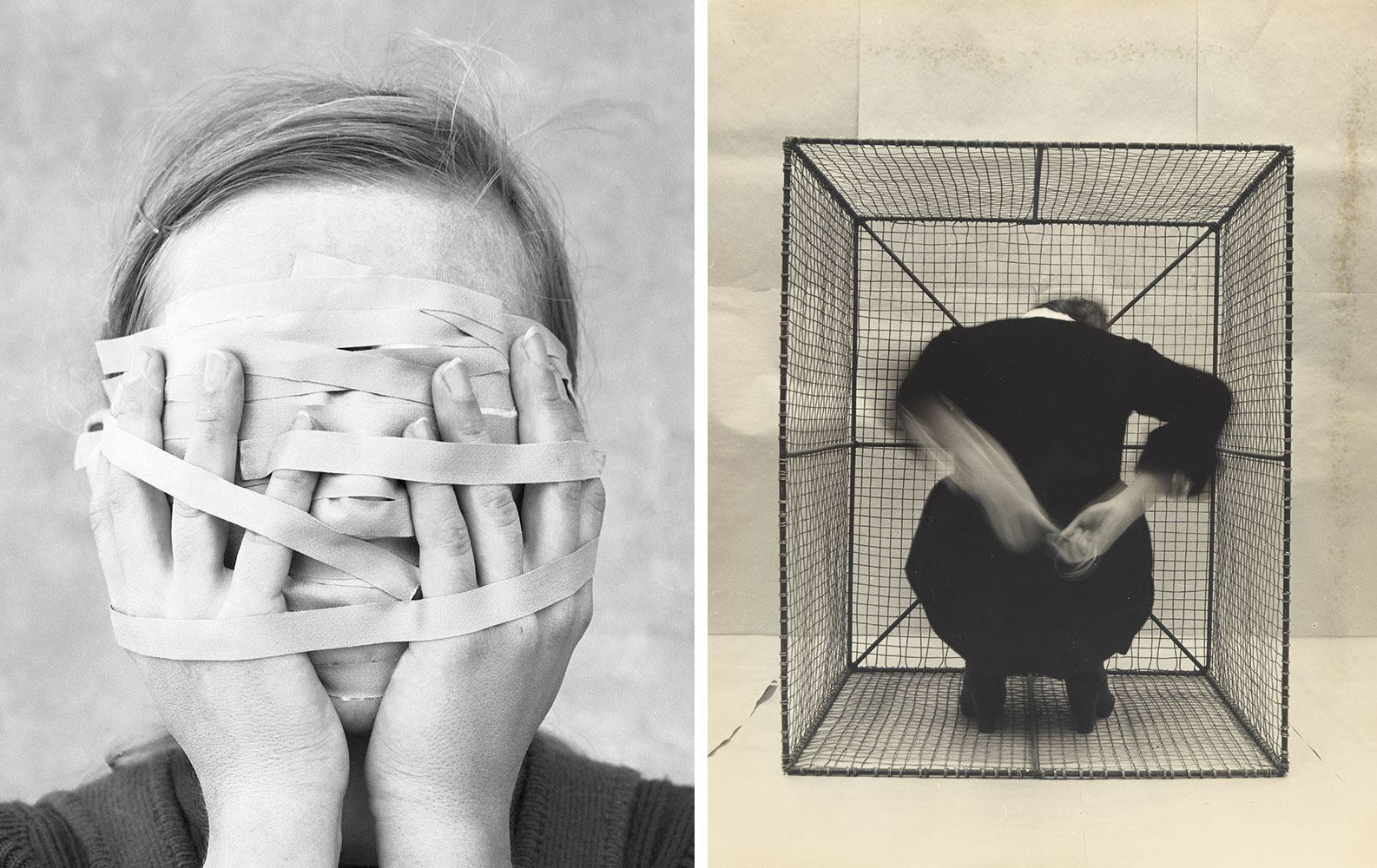

Marcella Campagnano joined Milan’s Via Cherubini feminist group in the early 1970s. The group developed a project on female identity centred on creating commonplace images of femininity. Photography struck Campagnano as the right medium to record what she describes as an “ironic theater of experience”. In 1974, Campagnano began work on a photographic series that turned her small apartment into a makeshift photographic studio. Deftly combining the contents of her wardrobe with makeup and gestures of the sort women perform in everyday life, she slipped into different feminine roles, using a mirror to fine-tune her facial expressions and poses. In the photographs she appears variously as a wife, young lady, working woman, mother, student, love-struck girl, lady, pregnant woman, prostitute, bride and paramour. The resulting series, which received the title “L’Invenzione del Femminile: RUOLI”], was not intended purely as a work of art. Campagnano also hoped it would ignite a political discourse. It highlighted how the roles women play are constructions imposed by patriarchal society. The photographs expose the image of women to be one of objectification enacted by the male gaze. Renate Eisenegger saw for herself how women artists played only a background role, while studying at the Academy of Art in Düsseldorf. It was not until she moved to Rome in 1972/73 that she felt able to work without any form of discrimination or repression. During her time in Italy she created works such as “Kabuki-Fries” (1972), a series of 12 black-and-white photographs where she painted her face white and then covered it with horizontal and vertical lines thus erasing her identity as a subject. The use of a mask-like painted face gave Eisenegger a sense of self-detachment and provided considerable artistic freedom. For her performance piece “Hochhaus”, which was staged without an audience in a tower block in Hamburg in 1974, she again painted her face white. During the performance she moved along a long corridor in a crouched position, ironing out the smooth linoleum flooring. The emotional emptiness of the female protagonist reflects the oppressive atmosphere of this anonymous high-rise architecture. Eisenegger’s eight-part photo series “Isolamento” (1972) shows a woman sticking cotton wool and tape over her mouth, then over her nose, ears and eyes, before finally tying up her head and hands completely. This oppressive act of blocking all means of communication acknowledges a collective female experience that has long been an issue for the women’s movement.

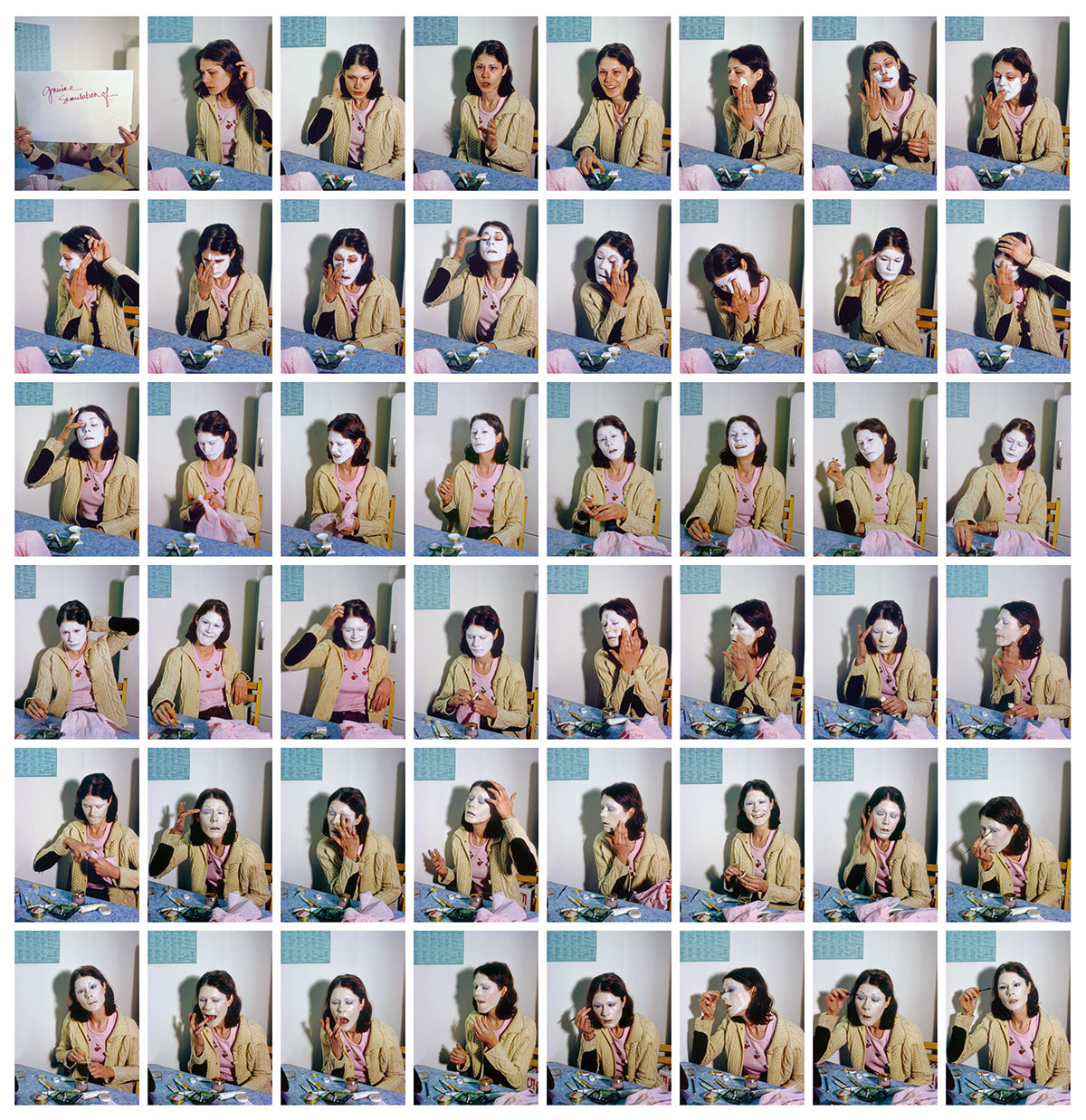

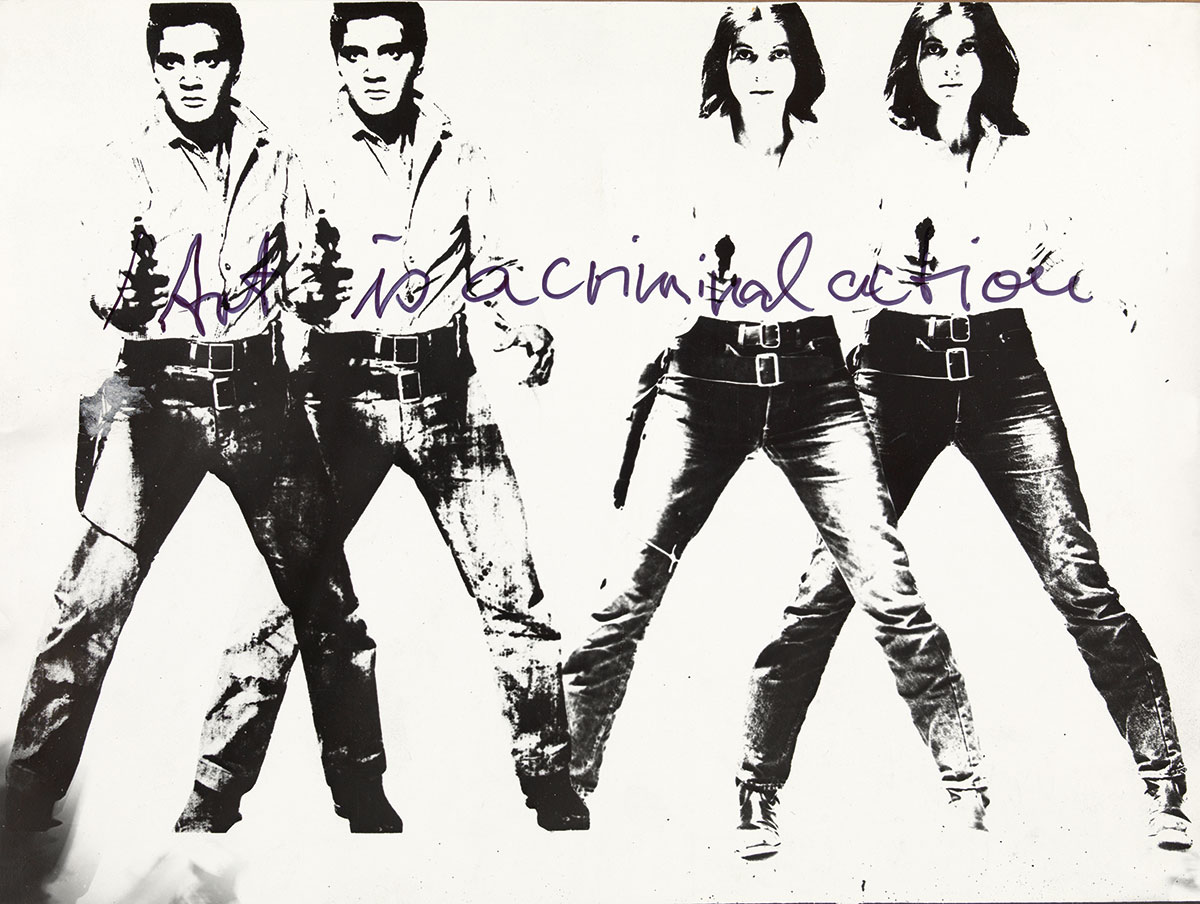

Kirsten Justesen began to use her own body as a sculptural tool in 1968 while still a student at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. Her experimental, feminist approach challenged both art-historical tradition and the contemporary avant-garde. In “Sculpture # II” (original title: Kasse [Box], 1969) Justesen critiques the de-personalised, minimalist tendencies of the time – particularly sculpture. Mimicking its basic forms, with a cardboard box presented on the gallery floor, she subverts its disembodied intellectualism through the addition of a photograph of a crouching naked woman, placed as if she is inside the box. Here the artist confronts the objectification and entrapment of the female form throughout art history as well as calling attention to the avant-garde understanding of the body as a de-personalized tool. Suzy Lake is an American-Canadian artist, well known for her works as a photographer, performance artist and video maker. She is a pioneering feminist and politically-minded artist. In the1960s, Lake became involved with the anti-war and civil rights movements and witnessed the Detroit Race Riots of 1967, one of the deadliest riots to occur in the United States. Because of the political events, she moved with her husband to Canada, where she studied at the Concordia University in Montreal. In her art, she explores topics including female identity, transformation, beauty and gender. The work “MISS CHATELAINE” (1973/1998) reflects change in female identity. For the work she collaged a range of trendy hats and hairstyles culled from various fashion magazines over some older portraits of herself. The title MISS CHATELAINE was a simple reference to a fashion magazine archetype aimed at young women. The artist chose it because it was an understood example of how women were represented in the 1960’s and 70’s. “IMITATIONS OF MYSELF” (1973/2012) shows the process of putting on make-up through serial photography. In the work, we see the artist sitting at a table, looking in the mirror and applying make-up to her face: «If one was a feminist or an activist, the white face had a double function as a mask—to hide behind or to reveal.» Lake’s use of seriality and grid structures echoes the Conceptual and Post-Conceptual art. Ulrike Rosenbach studied sculpture at the Academy of Art in Düsseldorf, where she was taught by Joseph Beuys, among others. By 1969 she had set up a women’s artist group and established links with the women’s liberation movement in the United States. This led her to found the Schule für Kreativen Feminismus (School for Creative Feminism) in Cologne in 1976. Rosenbach began experimenting with video technology in 1972, a medium that enabled her to have further control over how her own image was seen. In her performance “Glauben Sie nicht, dass ich eine Amazone bin” (1975), she used two video cameras to film herself shooting 15 arrows at a reproduction of Stefan Lochner’s iconic painting “Madonna of the Rose Bower” [c.1450]. The recorded images were then superimposed and shown on a video screen. In this work Rosenbach attacks both the image of the Madonna, free of all sin; and the eroticised image of the warrior-like Amazon. Rosenbach’s interest in challenging stereotypical depictions of women also underlies “Weiblicher Energieaustausch” (1975-76) where she has superimposed photographs of herself on reproductions of famous paintings. In “Art is a Criminal Action No. 4” (1969-70), she presents herselfas a female counterpart to Elvis Presley in Andy Warhol’s famous image.

Works by: Helena Almeida, Emma Amos, Sonja Andrade, Eleanor Antin, Anneke Barger, Lynda Benglis, Renate Bertlmann, Tomaso Binga, Dara Birnbaum, Marcella Campagnano, Elizabeth Catlett, Judy Chicago, Veronika Dreier, Orshi Drozdik, Lili Dujourie, Mary Beth Edelson, Renate Eisenegger, VALIE EXPORT, Esther Ferrer, Marisa González, Eulàlia Grau, Barbara Hammer, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Alexis Hunter, Mako Idemistu, Birgit Jürgenssen, Kirsten Justesen, Anna Kutera, Ketty La Rocca, Leslie Labowitz, Suzanne Lacy, Katalin Ladik, Suzy Lake, Natalia LL, Lea Lublin, Karin Mack, Dindga McCannon, Ana Mendieta, Annette Messager, Rita Myers, Senga Nengudi, Lorraine O’Grady, ORLAN, Gina Pane, Leticia Parente, Partum, Friederike Pezold, Margot Pilz, Howardena Pindell, Ingeborg G. Pluhar, Angels Ribé, Ulrike Rosenbach, Martha Rosler, Brigitte Aloise Roth, Victoria Santa Cruz, Suzanne Santoro, Carolee Schneemann, Lydia Schouten, Elaine Shemilt, Cindy Sherman, Penny Slinger, Annegret Soltau, Gabriele Stötzer, Betty Tompkins, Regina Vater, Marianne Wex, Hannah Wilke, Wilson, Francesca Woodman, Nil Yalter, Jana Želibská

Photo: Howardena Pindell, Free, White and 21 (Video still), 1980. Video, duration 12 minutes and 15 seconds, © the artist; VERBUND COLLECTION, Vienna; courtesy Garth Greenan Gallery-New York

Info: Curator: Gabriele Schor, Mécanique Générale, 35 Av. Victor Hugo, Arles, France, Duration: 4/7-25/9/2022, Days & Hours: Daily 10:00-19:30, www.rencontres-arles.com/en

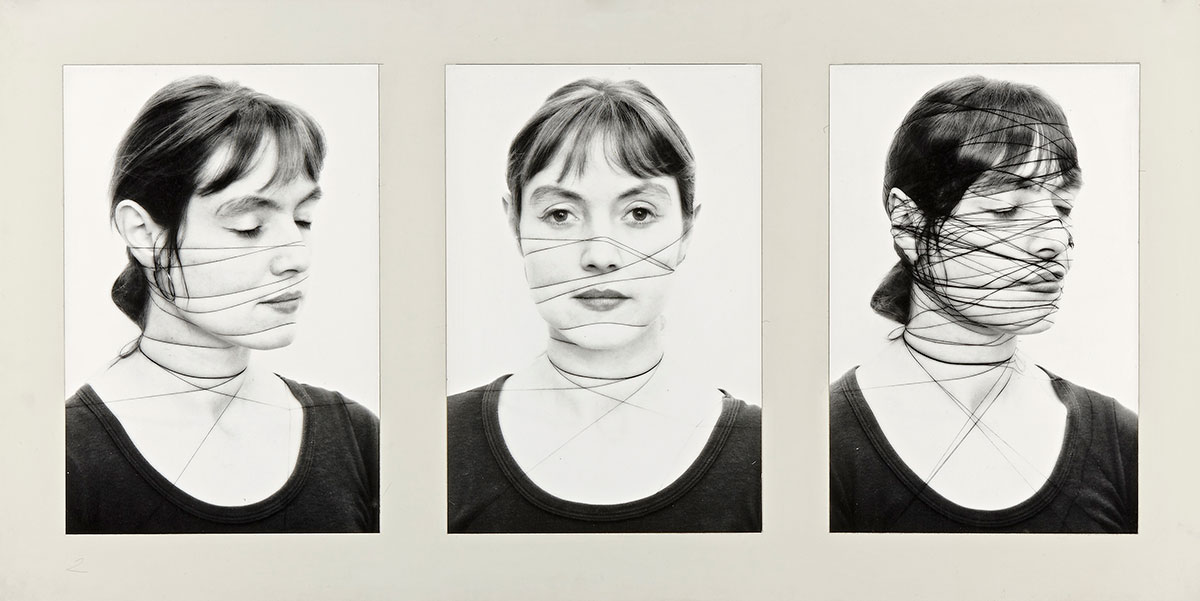

Right: Annegret Soltau, Vagina I, 1978. Photograph overstitched with black thread, 123.5. x 106.9 cm, © the artist; VERBUND COLLECTION, Vienna; courtesy Anita Beckers, Frankfurt; Richard Saltoun Gallery, London; Bildrecht, Vienna

Right: Orshi Drozdik, Individual Mythology. Cage, 1976. Gelatin silver print, 27.4 x 21.4 cm, © the artist; VERBUND COLLECTION, Vienna; courtesy Knoll Galerie, Vienna