PHOTO: Tokyo Revisited-Daido Moriyama with Shomei Tomatsu, Part II

Describing themselves as “stray dogs running through the city while unconsciously looking around”, Daido Moriyama and Shomei Tomatsu take pictures of everyone who moves in front of them. The exhibition “Tokyo Revisited Daido Moriyama with Shomei Tomatsu” offers a full immersion into post-war and contemporary Tokyo with hundreds of works by one of the best living Japanese photographers, Daido Moriyama (1938- ), and by his late mentor Shomei Tomatsu who passed away 10 years ago (Part I)

Describing themselves as “stray dogs running through the city while unconsciously looking around”, Daido Moriyama and Shomei Tomatsu take pictures of everyone who moves in front of them. The exhibition “Tokyo Revisited Daido Moriyama with Shomei Tomatsu” offers a full immersion into post-war and contemporary Tokyo with hundreds of works by one of the best living Japanese photographers, Daido Moriyama (1938- ), and by his late mentor Shomei Tomatsu who passed away 10 years ago (Part I)

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MAXXI Archive

A seminal photographer of lyrical, expressionist sensibility, Daido Moriyama has restlessly portrayed the emotional condition of everyday postwar Japan. He belongs to the generation who matured in the decades following Japan’s surrender—who lived in urban centers and experienced the country’s submission to occupation and political pressures by its “liberators,” as well as its emergence as a vibrant economy. These and other factors stimulated a period of radical art-making. Shomei Tomatsu created pictures that balance perilously between despair and admiration, anger and delight, articulating the essential conflicts he found in his country after World War II. Sharp and elegant, they are not so much descriptions as they are records of fleeting, unremarkable moments. The first photographer to explore the experience of postwar Japan and its ambiguous relationship to the United States, Tomatsu would portray this subject more thoroughly and intensely than any other photographer. Roaming around like nomads or stray dogs – to quote the title of one of Moryama’s most famous works, “Misawa” (Stray Dog), 1971, which he has often identified as a self portrait – the two artists criss-crossed the streets of Tokyo taking pictures of all that moved under their eyes, not seeking beauty, but exploring and showing every corner of the city. While Tomatsu was more focused on social and political aspects, Moriyama, with his trademark “grainy, blurry and unfocused” style, plunged himself with glee in the overwhelming spectacle of the consumerist society. Both artists treat photography as a way of life rather than as an artistic genre. And both are eminent representatives of a unique photographic style born and rooted exclusively in the urban context of Tokyo, which stands out in the global artistic panorama as one of the most original, dynamic and poetic expressions of art. The exhibition “Tokyo Revisited Daido Moriyama with Shomei Tomatsu” is spread out over 500 images, most of which (370) are original prints from Japan, along with a kaleidoscope of prints that form gigantic wallpapers covering an area of 600 square metres. Moriyama’s photographs, displayed on yellow walls, are alternated with those of Tomatsu, set against a light blue backdrop. Through them, visitors are encouraged to explore the city of Tokyo, let themselves be carried away and get lost in a world of images, sounds, colors and projections.The exhibition is divided in the following sections:

A Book World: The works by both Tomatsu and Moriyama are prominently utopic. This utopian dimension, recurrently interrupted by dystopic events, actually prompts a ‘virtual reality’ without computers and the internet. There is a long tradition of image book production and consumption in Japan – with Manga as its most popular expression – forming a widespread method of sharing observations, emotions, and fantasies in people’s lives. They are an indispensable element of urban life and a significant expression of the ongoing transformation of a public sphere. They are a form of social media that predates the digital era. Photography is primarily distributed and communicated in a printed format. Japanese photographers have produced a huge amount of photo-books, magazines, etc., which occupy a central position in both artistic and popular culture. Along with Tomatsu, Moriyama represents a pinnacle of this mass production, with a large number of books and, especially, his self-printed magazine Provoke (1969), now considered a landmark in the history of photography, and his ongoing project Record (from 1972), which embodies his most urban expression.

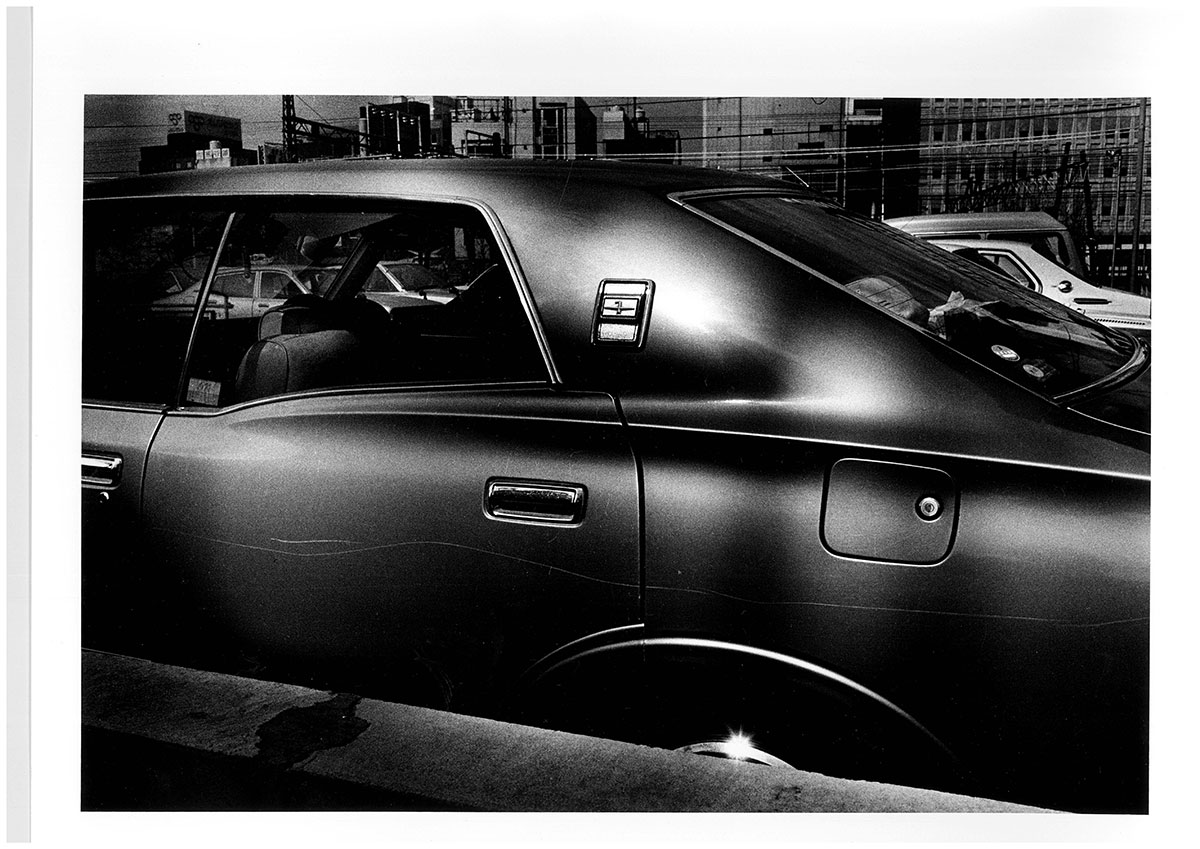

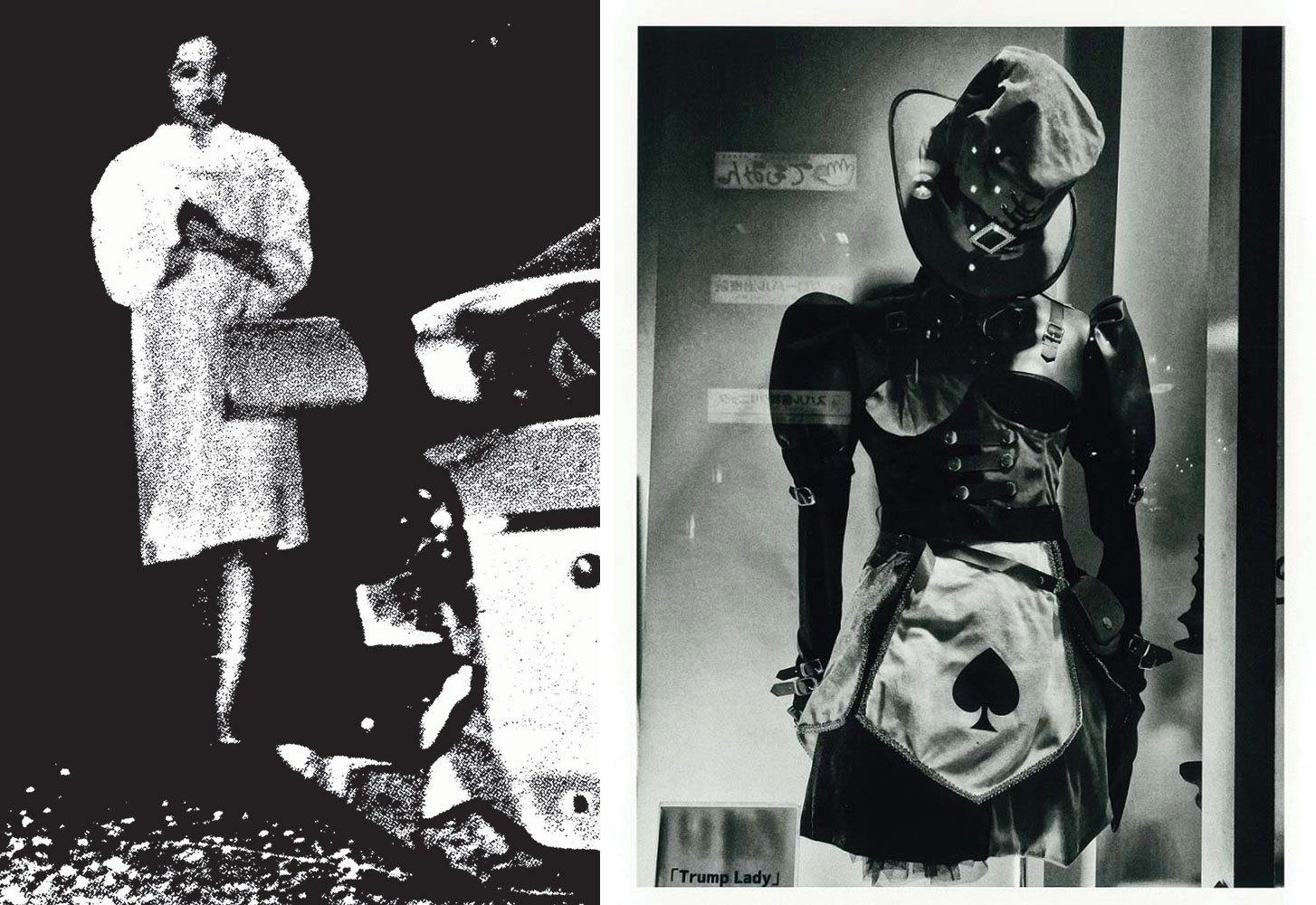

A Floating World: After World War II, and especially since the 1960s, Tokyo has become an epicentre of urban mutation. The acceleration of modernization and expansion have turned the quiet imperial capital into an exciting cosmopolis. The city, lit by dazzling neon signs, car lights, street lamps, advertisement panels, etc., is now a colourful and intriguing screen for the projection of new fantasies, visions, and illusions, prompted by the consumerist and liberal society many of which, captured in the series “Pretty Woman” (2017). This has profoundly transformed the collective psychology, values and social relationships. New forms of beauty and ugliness, with a certain ‘mundanity’, have been generated. The city is now a new ‘floating world’, bringing traditional Ukiyo-e genre painting back to life. This offers the best source of inspiration for artists, with photography as one of the most immediate mediums leading the crowd on daydream-like journeys through the mutating streets. Tomatsu and Moriyama are among the most original and attractive figures in this artistic trend, inviting the public to enter into real adventures of urban exploration through their radical photographic images.

Two World-Class Masters: Contemporary, Japanese photography is now widely recognized as a powerful force on the global art scene. Tomatsu and Moriyama, among others, are the most outstanding masters, or world-class masters. Tomatsu established himself in the late 1950s as a leading figure in the world of photography, while Moriyama, eight years his junior, joined him in Tokyo in the early 1960s to start his own career. Based in Tokyo, they have invented audaciously innovative photographic languages, interacting with international experimental movements in art, literature, and theatre, as well as popular culture from the Beat Generation to William Klein via Andy Warhol. While sharing interests in recording ordinary scenes from the most surprising angles, they also distinguish themselves through different, somehow opposite areas of focus: Tomatsu tended to concern himself with socially and politically engaging scenes unfolding within the city from the standpoint of an activist (as in works produced in 1954–58 and in the “Protest” series of 1969); Moriyama enjoys merging himself in the flux of fun and enjoyment produced by the overwhelming spectacle of the consumerist society, without forgetting to reveal its “ugliness”. Moriyama considers Tomatsu to be his master. It’s an honour for him to exhibit alongside Tomatsu in a double monographic exhibition.

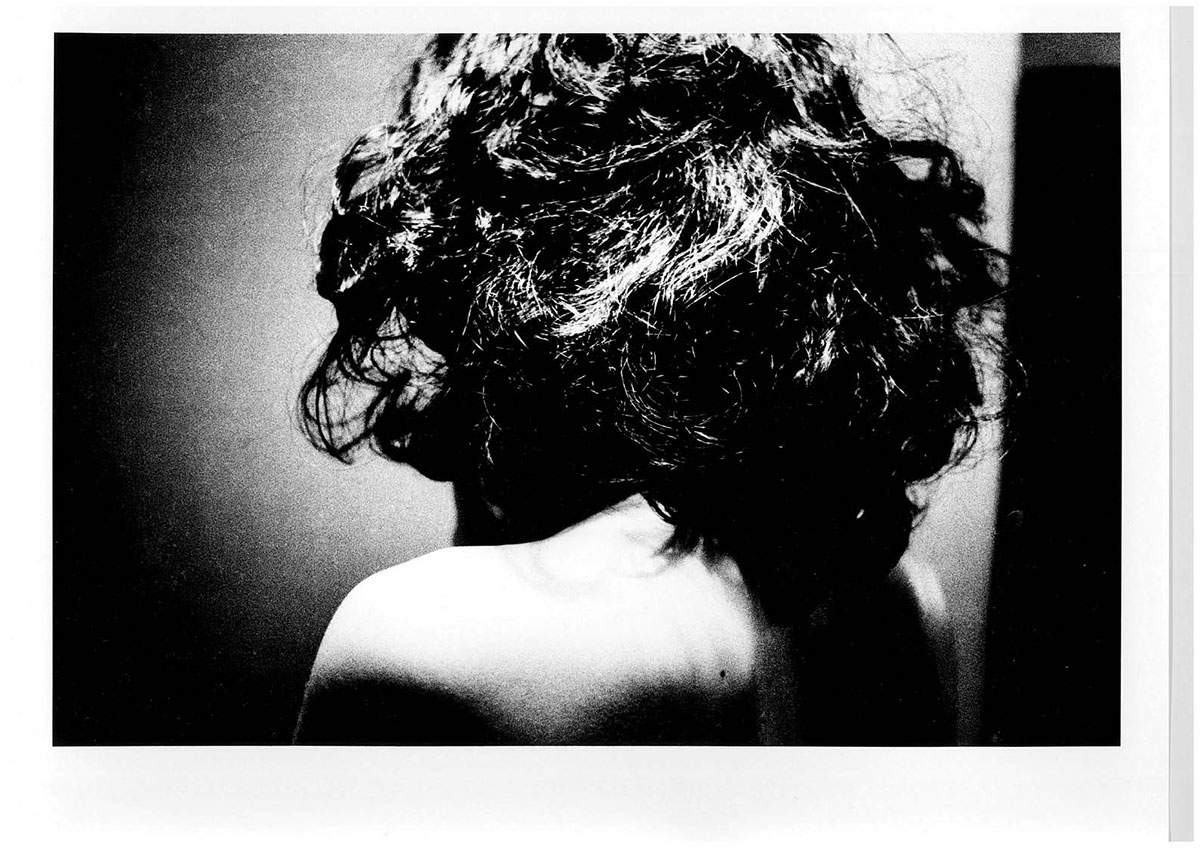

Shinjuku, The Dark World: Shinjuku is a notorious “red-light district” in Tokyo, home to a maze of obscure lanes and bars with dimmed lights. However, all sorts of enjoyment, pleasure and ‘decadent acts’ radiate from within the darkness … At the same time, a veritable underground world of alternative artistic creation and social encounter has thrived in this realm of fleurs du mal … It’s the neighbourhood where Tomatsu and Moriyama live and which they most frequently explore. Here, they have ‘snapshot’ some of the most pungent details of rebellious lifestyles and signs of resistance, turning them into some of the most impressive images in the history of photography. In a way, Shinjuku has allowed them to become real masters. In the meantime, it’s also because of their photographic creations that Shinjuku has become one of the most photogenic “sight-seeing spots” in Tokyo. For many, it is thanks to Tomatsu and Moriyama that Shinjuku has become what it is today.

The Stray Dog’s World: Both Tomatsu and Moriyama treat photography as a way of life rather than a category of art. Their lifestyle is nomadism, best represented by Moriyama’s famous image A Stray Dog, which he has often identified as his own portrait. This “identification” was derived from Tomatsu’s text “The Gaze of A Stray Dog”, which recounted his experience as an urban nomad. He said: “However, when there is no home to go back to, I found that the route tends to become somewhat random, going in a zigzag, and with an unfocused gaze. I caught myself looking down and staring at the ground as I walked, very much as if through the eyes of a stray dog. Only when adopting the gaze of a stray dog did those things that I used to see but wasn’t really aware of, those little details, suddenly look so familiar when they appeared before my eyes.”

The World Inside: An urban nomad also needs to look for anchor points that can help him feel somehow safe. It’s about looking inside oneself in order to understand one’s real Self. The world inside reflects the world outside. As Moriyama demonstrates, this can happen in contrasting ways: either by snapshotting one’s image in a mirror, or catching one’s shadow cast by the sunshine or moonlight. Even more interestingly, one can discover the common “inside” of all human beings by photographing tubed foetuses in Kanagawa hospital … or so we are told by Moriyama’s early series “Pantomime” (1964). Eventually, one’s inner world is the seed that creates the outer world, something that one can only grasp by meditating upon one’s own shadow.

A World of Performance: Tokyo is a city of performance. Actors have always played a key role in creating the collective imagination, an evolving force that shapes a cultural identity, with art spaces dotting the urban landscape. Tomatsu and Moriyama have built intimate relationships with the world of performance. Facing a post-disaster world to which new disasters are being added – the loss of cultural identity and human dignity due to overwhelming ‘Americanisation’ and capitalistic alienation – the performers, resorting to their facial expressions, body movements and voices, launched a revolt against human alienation. They have formed avant-garde movements named Neo-Dada, Butoh, experimental Noh, etc. Both Tomatsu and Moriyama used their cameras to record the performances and their protagonists, such as the musician in Chindon Street or the actor Shimizu Isamu. The works, many of which presented in Japan, “A Photo Theater” (1968), have not only provided articulated angles of appreciation, but also opened a new perceptive space for the audience to engage emotionally with the actors and to perform their own imaginative acrobatics.

The Lost World: For Tomatsu and Moriyama, to be a photographer is to be homeless or an aimless flâneur, guided by whatever emerges before or beneath his eyes. The photographer merges with the urban crowd and rubs shoulders with others. This renders him particularly sensitive to all sorts of alternative materials, from objects to street signs (Light and Shadows, 1982), small details, lost animals, debris (Lettre à St Loup, 1990), from secret love, blunt violence (Monochrome, 2008–2012), car accidents (Accident 2016 – inspired by Andy Warhol’s series Death and Disaster and Scandalous, using the silkscreen print technique) to unexpected encounters with “abnormal” human figures and actions. By drifting in the city, they created a kind of machine désirante in the style of Deleuze and Guattari, which produces a “psychogeographic-mapping” system for Tokyo (and occasionally other cities that they visited). The “naked city”, or “naked reality” has been presented rather than the truth, as Moriyama argues.

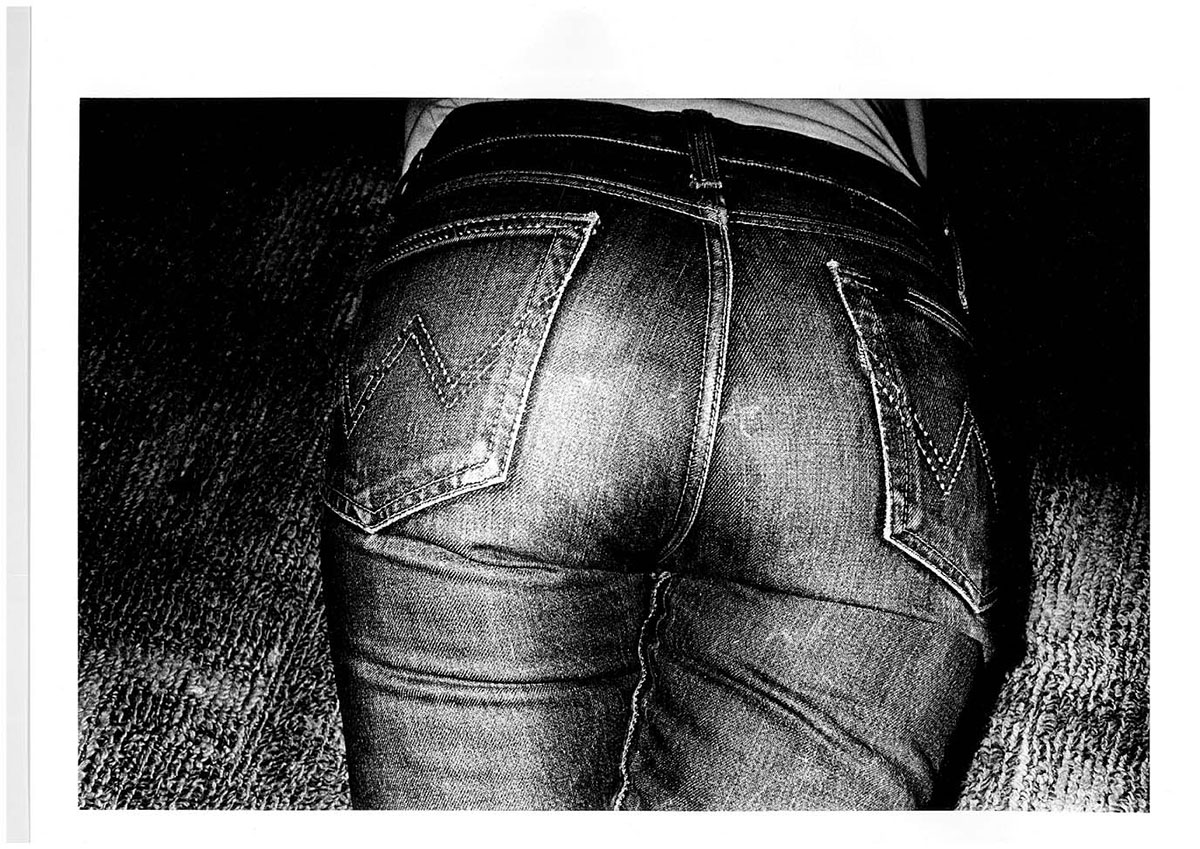

The World of Eros: For Tomatsu and Moriyama, the world is exposed to them in its ‘pure and naked’ state, without any beautifying ornaments demonstrating the process of sensual penetration of reality. It is almost a sexual act that leads them to “peep” into acts of sex, love, and objects of fantasy, revealing the forbidden beauty of real urban life. Here, photography resembles a real erotic affair. Images with endlessly repeated sexual connotations as in Tights (part of the How to Create a Beautiful Picture project, 1987), both direct and indirect, are not the only ones to have occupied a key place as elements of attraction. More interestingly, all the images have become somehow erotic and sexual because, by involving their cameras, they have managed to turn everything into a new life. Eros is life itself, echoing Marcel Duchamp’s unfathomable alter-ego: ‘Rrose Sélavy’. Moriyama said: ‘Isn’t life boring if one does not fall in love? If one does not fall in love with a human being, one must fall in love with something else. Falling in love does not have to be aimed at a human being, it can be wider-reaching, being in love with all kinds of things in the world …’

The World as an Infrastructure: Tokyo is an expansive conglomerate of urban zones. Connecting the quasi-infinite clusters of residential and working areas are all sorts of visible and invisible, above-ground and underground infrastructures that guarantee the normal functioning of the modern cosmopolis – electric cables, telephone lines, metro lines, railway tracks, waterways, drains… They form the skeleton, veins, and intestines of the urban body, allowing all living bodies to survive and grow. Along the spreading lines of the infrastructures, different scenarios of social life unfold and become stages of human comedies. Naturally, they seduce the attentive eyes of photographers like Tomatsu and Moriyama. Here, Moriyama’s Platform series (1977), with the Zushi-Yokohama-Tokyo line, manifests how an emblematic sign of modernity – the metro – can be turned into an artistic emblem in permanent movement.

Photo: Daido Moriyama. Pretty Woman (2012), © Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation, Courtesy Akio Nagasawa Gallery

Info: Curators: Hou Hanru and Elena Motisi, MAXXI (National Museum of 21st Century Arts), Via Guido Reni 4 A, Rome, Italy, Duration: 14/4-16/10/2022, Days & Hours: Tue-Fri 11:00-19:00, Sat-Sun 11:00-20:00, www.maxxi.art/

Right: Daido Moriyama. Pretty Woman (2012), © Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation, Courtesy Akio Nagasawa Gallery