TRIBUTE: The Shape of Freedom, International Abstraction After 1945

The exhibition “The Shape of Freedom: International Abstraction after 1945” focuses on the two most important currents of abstraction following World War II: Abstract Expressionism in the United States and Art Informel in Western Europe. The show comprises around a 97 works by 52 artists and is the first to explore this transatlantic dialogue in art from the mid-1940s to the end of the Cold War.

The exhibition “The Shape of Freedom: International Abstraction after 1945” focuses on the two most important currents of abstraction following World War II: Abstract Expressionism in the United States and Art Informel in Western Europe. The show comprises around a 97 works by 52 artists and is the first to explore this transatlantic dialogue in art from the mid-1940s to the end of the Cold War.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Museum Barberini Archive

The point of departure for the exhibition “The Shape of Freedom: International Abstraction after 1945” in the Museum Barberini is the Hasso Plattner Collection, which includes important works by Norman Bluhm, Sam Francis, and Joan Mitchell. World War II was a turning point in the development of modern painting. The presence of exiled European avant-garde artists in America transformed New York into a center of modernism that rivaled Paris and set new artistic standards. In the mid-1940s, a young generation of artists in both the United States and Europe turned their back on the dominant stylistic directions of the interwar years. Instead of figurative painting or geometric abstraction they embraced a gestural, expressive handling of form, color, and material—a radically experimental approach that transcended traditional conceptions of painting. Concurrently with Abstract Expressionism in the United States, artists in Paris and other European metropolises explored new materials, textures, and modes of composition. This new painterly approach was designated “Informel” due to its “formless,” unbridled aesthetic. West Germany likewise emerged as a center of European postwar abstraction from the mid-1950s on. As such, it cultivated close contacts with France and the United States. The exhibition documenta II in 1959 celebrated Art Informel and Abstract Expressionism as the manifestation of a new, universal visual language that would strengthen the political alliance of liberal western nations. In West Germany, radical abstraction was hailed as the new standard for avant-garde painting, in contrast to the Socialist Realism of East Germany or the aesthetic principles of the Nazi regime. Sections of the exhibition:

A New Avant-Garde, Abstract Expressionism: In the 1940s, New York took its place alongside Paris as a leading international center of modern art. Due to World War II, many members of the European avant-garde had emigrated to the United States, and young American painters encountered the work of these exiles in galleries like Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century. This dialogue played a decisive role in the development of Abstract Expressionism. Although they did not adopt a single, uniform style, the artists were united in their conviction that painting was more than the mere rendering of external reality. Instead, they viewed the canvas as a stage on which creative energies should be allowed to unfold freely and spontaneously. Intuition, expressive gestures, and the exploration of the unconscious and irrational were their most important concerns. Despite the abstract pictorial language, their works often include figurative elements or allusions to traditional genres such as landscape, still life, or interiors. In many cases, they also bear witness to the influence of the European avant-garde, echoing the flat spatial structures of Cubism or the organic forms of Surrealist painting.

Gestures of Freedom, American Action Painting: Even before World War II, the Surrealists in Paris had already developed numerous techniques for integrating chance elements into the design of their pictures. They used semiautomatic processes to develop a direct, dynamic approach to painting, working rapidly and without preliminary planning in order to release the creative powers of the unconscious. In their so-called “action painting,” the Abstract Expressionists drew inspiration from their older European counterparts. For the most part, their expressive, brilliantly colored works were also executed without preparatory planning. They interpreted the physical act of painting as a performative gesture, covering the canvas with a free play of color and form marked by powerful strokes and energetic brushwork. Many of the artists were fascinated by the depth psychology of C. G. Jung and his theory of the collective unconscious. Like the Surrealists, they sought to create a material reflection of their own inner life, one that would address the viewer intuitively and emotionally. Furthermore, they conceived of this spontaneous, gestural approach as a rejection of traditional academic rules and thus as the expression of artistic freedom and self-assertion.

Unbounded Pictorial Space, All-Over Effects: The Abstract Expressionists sought to redefine the relationship between figure and ground. They avoided spatial illusionism and emphasized the presence of the canvas as a two-dimensional surface. Often every part of the painting is equally developed, leaving the composition without an identifiable center. Concepts such as “above” or “below,” “foreground” or “background” have little meaning in context of these nonhierarchical, “all-over” compositions. The painting often appears as an arbitrary section of a visual field that can be imagined as continuing beyond the borders of the canvas. For his so-called drip paintings, Jackson Pollock spread the canvas on the floor of his studio and covered it with densely tangled threads of color, dripping, spattering, and pouring the paint onto the surface in rhythmic, dance-like movements. Beginning in the early 1950s, this revolutionary new technique also influenced the development of European abstraction. Though lacking in geometric structure, such compositions are often characterized by a decorative quality.

Immersive Images, Color Field Painting: Along with action painting, another approach also developed within Abstract Expressionism: color field painting. Here the artists created rhythmic arrangements of pictorial zones using only a few colors. The works were large, at times even monumental in scale and negated any sense of spatial depth. Many are intended to be viewed at close range, inviting viewers to contemplatively immerse themselves in the visual field. Artists like Mark Rothko or Barnett Newman associated the meditative quality of their paintings with a kind of spiritual vision. Their respective approaches to visual form, however, diverged sharply: while Rothko’s works are characterized by gently pulsating, soft-edged fields of color, Newman used clear vertical bands and edges to partition the monochromatic ground of his pictures. This formal reduction reinforced the tendency toward flatness already manifested in the large-scale water lily paintings of Claude Monet.

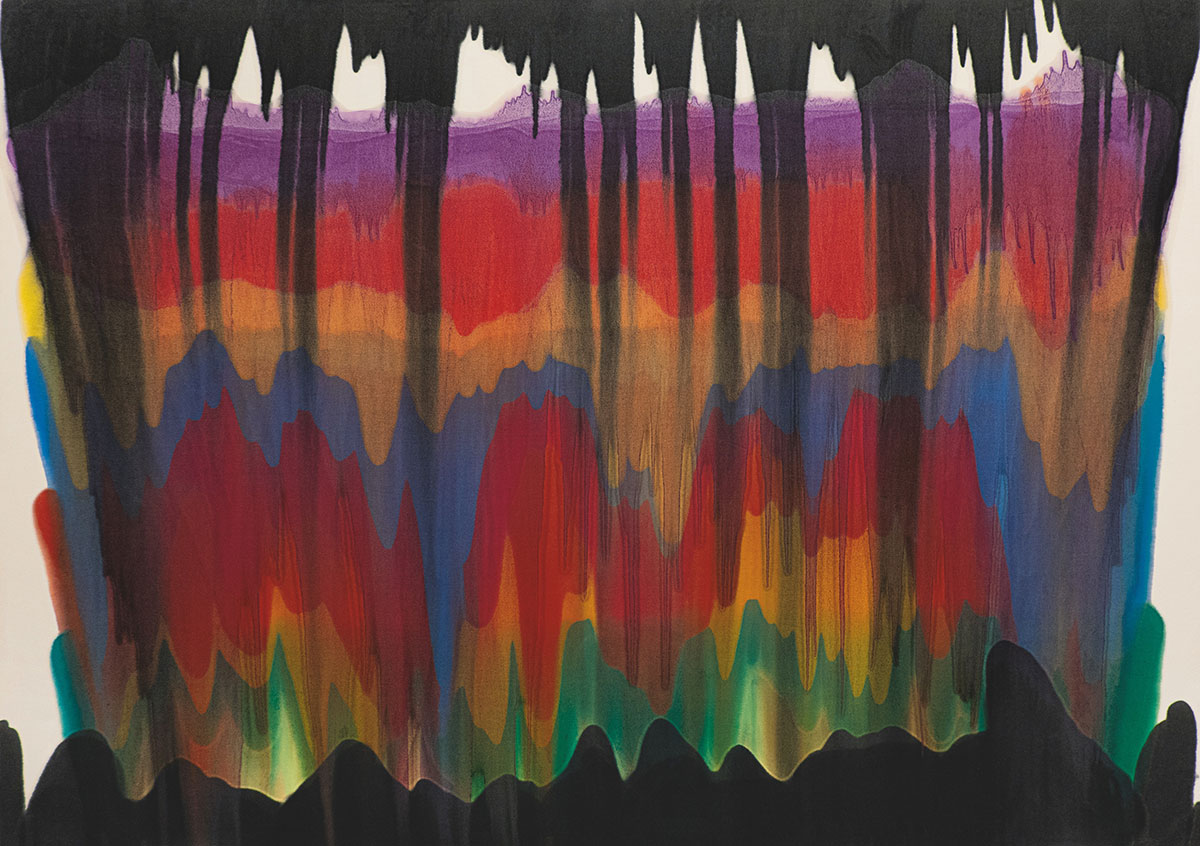

Flowing Color, The Staining Process: Helen Frankenthaler developed a process in which she combined elements of both action painting and color field painting. In the early 1950s, she began pouring heavily thinned paint onto the canvas, allowing it to soak into the fibers. In its luminosity, her work recalls the transparent quality of watercolor. Like Jackson Pollock, Frankenthaler worked on unstretched canvases spread out on the floor, allowing the paint to flow freely across the surface as she lifted and moved the support. She often gave representational, associative titles to her nonobjective works. Frankenthaler’s fellow artist Morris Louis likewise used the so-called staining process for his color field paintings. He poured paint onto the canvas in a carefully orchestrated sequence of colors, creating a rhythmic pattern of glowing veils.

In the Footsteps of Monet, Abstract Impressionism: With the emancipation of color from form, the American postwar avant-garde embraced a tendency that had already characterized French landscape painting in the late nineteenth century. Sam Francis had encountered Abstract Expressionism in the late 1940s through the color field paintings of Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still. From 1950 on, he spent a number of years in Paris, where he studied the nature scenes of Claude Monet, including the water lily paintings. Francis’s large-scale abstractions show a luminous, decorative play of pulsating color fields, spatters, and splotches; their calligraphic character bears witness to East Asian influences. The American painter Joan Mitchell was also active in France for many years. In 1968 she moved to the Seine village of Vétheuil, where she lived near the former home of Claude Monet. Many of her expressive, brilliantly colored action paintings are reminiscent of sun-drenched landscapes.

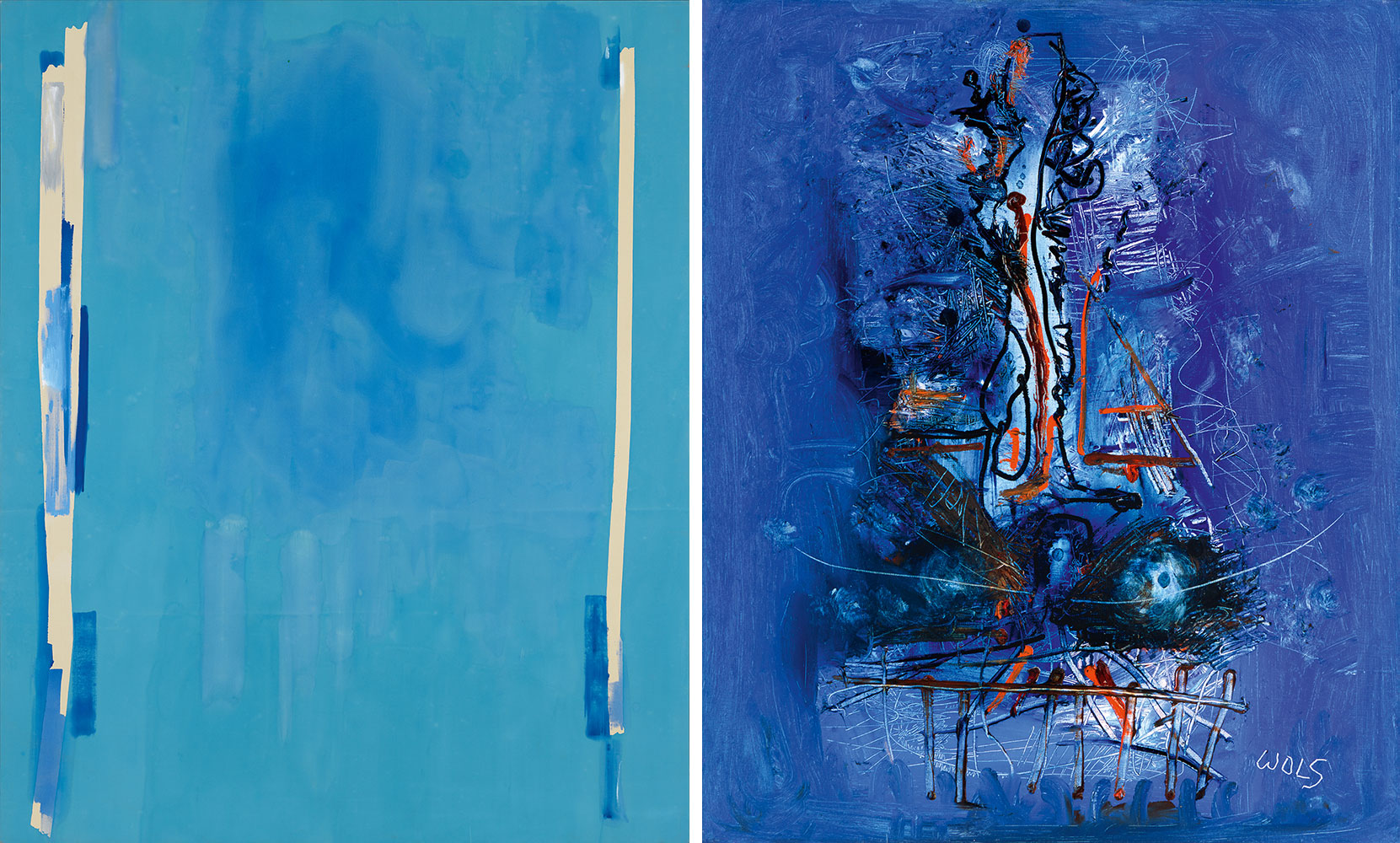

Dynamic Processes, The Painting of Art Informel: For European painters, as well, the 1940s were a period of profound change. Many of them had been directly involved in the war or had suffered under Fascist dictatorships. Just as in American art, figurative styles receded into the background. The painting of Art Informel developed in Paris and other western European metropolises parallel to Abstract Expressionism in the United States. Its open, “formless” pictorial structure was based on an improvisational approach to brushwork, surface texture, and material. In many works, scratches, holes, or gouges evoke the feeling of bodily wounds. In a postwar world traumatized by violence and Fascist terror, gestural painting served as an expression of the solitary individual’s existential search for meaning. Abstract Expressionist works were shown in Paris as early as 1947; shortly thereafter, the painting of Art Informel made its way to America.

Painting as Performance, European Action Painting: The late 1940s saw the development of a specifically European version of action painting. Through the work of the Surrealists, artists were already familiar with automatic processes of visual creation and continued to develop them in the painting of Art Informel. Other sources of inspiration were the decorative structure of East Asian calligraphy as well as the reduced color schemes of works in ink on white paper. Like Jackson Pollock, Georges Mathieu dripped fluid paint onto the canvas, creating action paintings marked by a calligraphic character. Many of these works were painted live in front of a large audience, completed in only a few hours in a burst of creative energy. In the early 1950s, Judit Reigl emigrated from Hungary to Paris, where she was initially associated with the Surrealists. Later, under the influence of the New York School, she experimented with gestural painting. In many works, she slung industrial paint mixed with linseed oil onto the canvas, using her bare hands or metal tools to spread it over the picture plane. The playful integration of her own body into the creative process situates her work at the threshold of new forms of expression such as Happenings and Performance Art.

Joining the Avant-Garde, Postwar Abstraction in West Germany: Under the Nazis, exposure to new developments abroad had been almost impossible for German artists. As soon as the war was over, young painters began cultivating close international contacts and traveled to Paris. West Germany emerged as a center of Art Informel in the early 1950s. Here, too, spontaneous, dynamic processes were embraced as the expression of a new sense of artistic freedom—a development favored by Germany’s unique role during the Cold War and the Federal Republic’s close ties with Western powers. As the antithesis of the Socialist Realism of East Germany, abstraction was politicized as the only valid form of expression for the democratic West. Thus many art historians celebrated abstraction as the “universal” visual language of free modernity—a construct of the postwar period that persists in art historical writing even today.

Color or Form? Modes of Abstraction: In the 1950s, Art Informel established itself as the dominant stylistic current of the West German avant-garde. Its affinity to American postwar abstraction manifested itself at documenta II in 1959. The exhibition in Kassel, subtitled Art After 1945, not only showed works by painters such as K. O. Götz, Ernst Wilhelm Nay, and Fritz Winter, but also included a room devoted to the oeuvre of Jackson Pollock. Many works created in response to Art Informel also show echoes of Abstract Expressionism. While the smoke and fire pictures of Otto Piene recall the cosmic iconography of Adolph Gottlieb, Rupprecht Geiger’s pulsating color fields allude to the painting of Mark Rothko. Yet their works were never mere imitations of established pictorial formulas: between the poles of action painting and color field painting, each artist engaged in an individual exploration of the tension between color and form, between the subjective gesture and the rational articulation of the picture plane.

Works by: Mary Abbott, Janice Biala, Norman Bluhm, Alberto Burri, Jean Degottex, Jean Dubuffet, Natalia Dumitresco, Jean Fautrier, Perle Fine, Sam Francis, Helen Frankenthaler, Winfred Gaul, Rupprecht Geiger, Arshile Gorky, Karl Otto Götz, Adolph Gottlieb, Hans Hartung, Gerhard Hoehme, Simon Hantai, Hans Hofmann, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Morris Louis, Georges Mathieu, Manolo Millares, Joan Mitchell, Robert Motherwell, Ernst Wilhelm Nay, Barnett Newman, Otto Piene, Jackson Pollock, Richard Pousette-Dart,mJudit Reigl, Ad Reinhardt, Deborah Remington, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Mark Rothko, Antonio Saura, Bernard Schultze, Iaroslav Serpan,mJanet Sobel, Theodoros Stamos, Hedda Sterne, Clyfford Still,Antoni Tàpies, Fred Thieler, Jack Tworkov, Emilio Vedova, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Fritz Winter, Wols.

Photo: Morris Louis, Saf Heh, 1959, Magna on canvas, 248 x 352 cm, ASOM Collection, © All Rights Reserved. Maryland Institute College of Art/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Info: Curator: Dr. Daniel Zamani, Museum Barberini, Humboldtstraße 5-6, Potsdam, German, Duration: 4/6-25/9/2022, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Fri 10:00-19:00, www.museum-barberini.de/

Right: Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze), Composition Champigny, ca. 1951, Mixed materials on canvas, 72 x 59 cm, MKM Museum Küppersmühle für moderne Kunst, Duisburg, Sammlung Ströher

Right: Karl Otto Götz, Giverny III/2, 1987, Mixed materials on canvas, 210 x 175 cm, Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf – Stiftung Sammlung Kemp, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Photo:Kunstpalast – LVR-ZMB – Stefan Arendt – ARTOTHEK

Right: Lee Krasner, Bald Eagle, 1955, Oil, paper and canvas collage on linen, 195,6 x 130,8 cm, ASOM Collection , © Pollock-Krasner Foundation/ VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Right: Mark Rothko, Untitled (Blue, Yellow, Green on Red), 1954, Oil on canvas, 197.5 × 166.4 cm, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, © Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Digital image: Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala

Right: Jackson Pollock, Enchanted Forest, 1947, Oil and alkyd enamel paint on canvas, 221,3 x 114,6 cm, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York), © Pollock-Krasner-Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Image: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York (Photo: David Heald)