BIENNALS: Whitney Biennial 2022-Quiet as It’s Kept

The Whitney Museum of American Art present the 18th edition of its flagship exhibition, the Whitney Biennial. Established in 1932 by the Museum’s founder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, it is the longest-running exhibition of its kind. Featuring sixty-three artists and collectives from a variety of generations, working across disciplines and media, the 2022 Biennial takes full advantage of the Museum’s unique architecture to present an exhibition that takes a look at the current state of contemporary art in America.

The Whitney Museum of American Art present the 18th edition of its flagship exhibition, the Whitney Biennial. Established in 1932 by the Museum’s founder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, it is the longest-running exhibition of its kind. Featuring sixty-three artists and collectives from a variety of generations, working across disciplines and media, the 2022 Biennial takes full advantage of the Museum’s unique architecture to present an exhibition that takes a look at the current state of contemporary art in America.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Whitney Museum Archive

Whitney Biennial 2022 features dynamic contributions that take different forms over the course of the presentation: artworks—even walls—change, and performance animates the galleries and objects. With a roster of artists at all points in their careers, the Biennial surveys the art of these times through an intergenerational group, many with an interdisciplinary perspective, and the curators have chosen not to have a separate performance or video and film program. Rather, these forms are integrated into the exhibition with an equal and consistent presence in the galleries. The title of the 2022 Whitney Biennial, Quiet as It’s Kept, is a colloquialism. Breslin and Edwards were inspired by the ways novelist Toni Morrison, jazz drummer Max Roach, and artist David Hammons have invoked it in their works. The phrase is typically said prior to something and sometimes obvious that should be kept secret. The majority of the exhibition takes place on the Museum’s fifth and sixth floors, which are counterpoints and act as pendants to one another: one floor is a dark labyrinth, a space of containment; and the other is a clearing, open and light-filled. The former also contains an antechamber, a space of reserve. The dynamics of borders and what constitutes “American” are explored by artists from Mexico, specifically Ciudad Juárez and Tijuana, and First Nations artists in Canada, as well as by artists born outside of North America.

In the film installation, “A Day Is a Day” (2022), Yto Barrada entwines a specialized visual vocabulary of age and decay with an exploration of motherhood, inheritance, and subjectivity. These forms, which often seem to accidentally refer to the history of modern art, actually describe fatigue and rot by processes that are imperceptible in real time. The footage was produced at two “weather acceleration” facilities across in Miami and Phoenix. The purpose of these industrial labs is to simulate the effects of the sun in a condensed timeframe to test the durability of consumer products and materials such as plastics, automotive and domestic parts, paints, and textiles against fading and corrosion. Workers share surreal fields and offices with machines, and it is the human eye that must be constantly calibrated as a tool of measurement. Barrada’s multidisciplinary work draws upon metaphor to emphasize the symbolic, political, and culturally specific context of abstract ideas and forms. She often presents standardized processes alongside their intensely personal ramifications. Here, color is configured as a measurement of time and the implacable degradations of exposure, evoking rites of passage between the marvelous and the monstrous. In his paintings, Jane Dickson considers the shared hopes and aspirations that commercial signs convey both in contemporary suburban spaces and in photographs she took of New York’s Times Square in the 1980s. She lived there when the city was, in her words, “burning, broke, and dangerous.” Both groups of paintings, the suburban and the urban, consider locations that are frequently overlooked or stereotyped. Dickson’s careful depictions suggest that a certain violence comes with making generalizations—in the writing off of those who lead their lives in areas that are frequently ignored or dismissed.

Dyani White Hawk made “Wopila| Lineage” (2022) by affixing loomed strips of thin glass bugle beads onto aluminum panels. Her art draws from the history of Lakota abstraction in beadwork, painting, and quill work, a traditional form of embroidery using porcupine quills. White Hawk also situates her practice in dialogue with that of abstract painters such as Barnett Newman and Jackson Pollock, who claimed Indigenous art as an influence. As she has stated: “Using glass beads references the history of cross-cultural trade relationships that have influenced the evolution of art forms over generations. Rick Lowe, who uses playing dominoes as the basis for his paintings, has talked about the symbolic qualities of the game as scenarios for community engagement. Lowe began by photographing and later tracing the patterns made by domino games, using them as a model for a form of abstraction grounded in lived experience. He finds playing dominoes to be “an incredibly spiritual and educational experience. There’s a code of ethics around the way the game is played; rigorous competition, humility, and respect”. Unable to travel to his hometown of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, during the pandemic, Alejandro Morales began looking for images of the city on Google Maps. Morales, who typically draws his materials from archival sources, found images of Juárez that document everyday scenes as well as evidence of the drug war and militarization that have impacted this city that shares a border with Texas, especially between 2008 and 2013. The result is what the artist has called a “taxonomy not just of the city but also of the aesthetics of Google’s processing: glitches, overlapping, and blurring as well as the city’s architecture, flowers and trees, working people, animals, and its militarization.”

Lucy Raven’s “Demolition of a Wall (Album 1)” is the second moving-image installation in her trilogy of “Westerns.” In American cinema, the Western has traditionally celebrated the expansionist myth that the region is somehow primal or untouched. Raven, by contrast, engages with a West that—while still dramatic in its natural beauty—has been industrialized, militarized, and colonized. She filmed this work at an explosives range in New Mexico that is typically employed as a test site by the US Departments of Defense and Energy and private munitions companies. Notably, it is close to Los Alamos, a national laboratory known for its role in the development of the nuclear bomb. Using a variety of cameras and imaging techniques, Raven captures the trajectory of the pressure-blast shockwaves that move through the atmosphere in the wake of an explosion. Drawing on film technologies designed for scientific analysis, she turns away from the Hollywood need for a climax, instead presenting the shocks as subjects in themselves. The installation “Ninety-Nine Bottles of Beer on the Wall” (2021) features three new sculptures by Charles Ray: a man staring blankly, a man eating a burger, and a drunken man. Carved from stainless steel, steel, and cast in bronze and painted, these sculptures combine cutting-edge technology and skilled handwork. He works slowly and meticulously, often spending years on each sculpture. His figures are both extremely specific and archetypal. But the sculptures can also be read as emblems of our historical moment: drug-altered, precariously employed, drunk on beer and debt. Ray, an inveterate walker, has described a daily routine that informs his thinking: “I go to Burger King every day, not to eat but to think. I went to one in Madrid at four in the morning; it’s just like the one in LA, identical. Who is there, and what are they being promised?

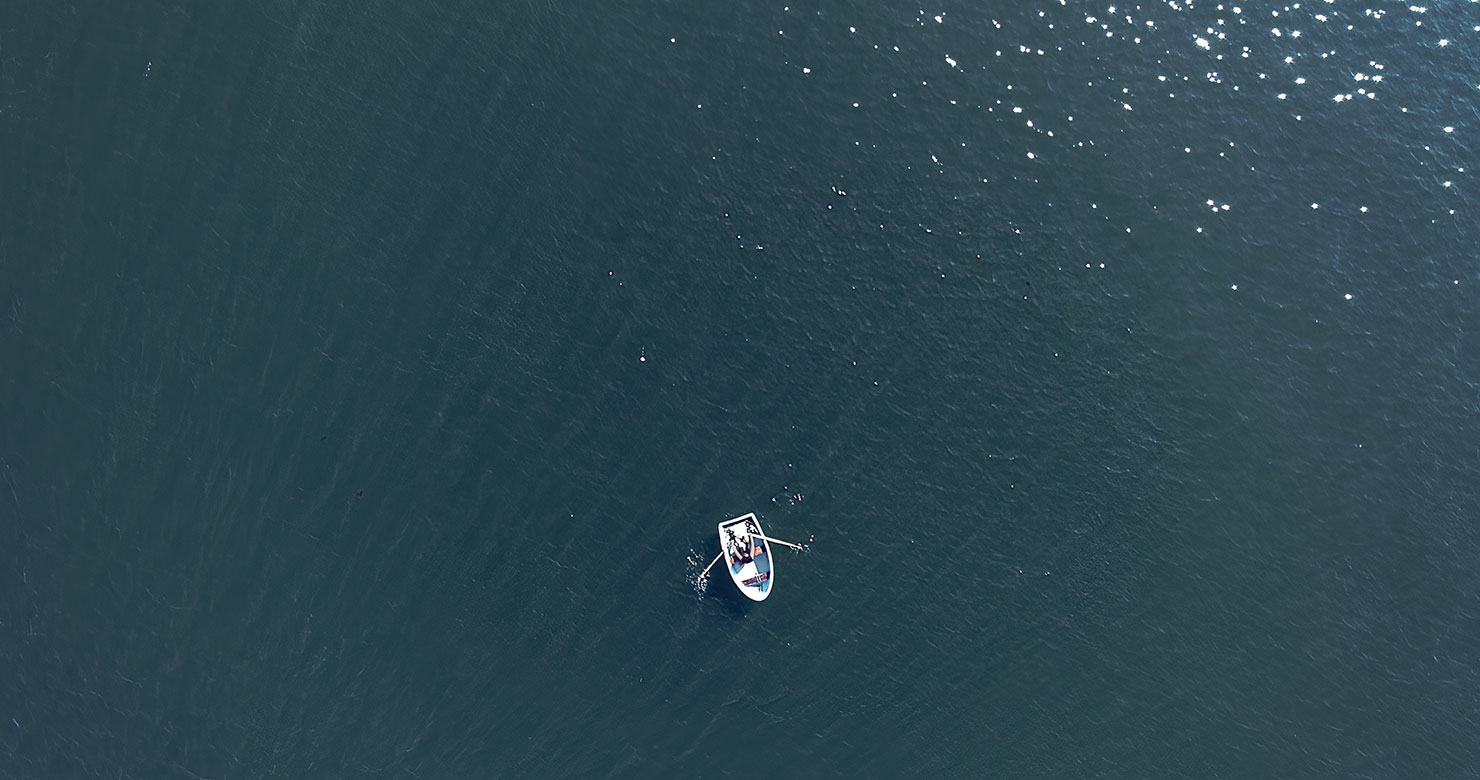

To create the sculpture installation “Between a Rock and a Hard Place” (2022), Veronica Ryan combined found and fabricated materials. She employed shelving and different modes of display to consider ideas of classification and how objects, like people, hold histories of migration and displacement. Ryan’s fabricated objects might look or feel familiar, depending on the viewer’s experience. The meanings are poetic, personal, and associative: the cast bottom of a water bottle might suggest a magnolia flower; handmade objects resembling cashew seeds could promise sustenance. The video “Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word” (2021) by Coco Fusco includes footage of the artist traveling by boat around Hart Island, the site of New York’s public cemetery that was operated by the city’s department of corrections until October 1/10/2021. Since 1869, prison labor has been used to bury more than a million New Yorkers in mass graves on the island. Many individuals have been buried anonymously—especially during epidemics. Fusco’s video features a meditation she wrote on the conditions of the current pandemic and is performed by poet Pamela Sneed. Cy Gavin’s recent paintings conjure landscapes and the natural world. His imagery frequently starts from his observations of his immediate surroundings, but his selections also carry metaphorical weight. Recent paintings have depicted cosmic phenomena, a failing human-made dam patched by beavers, native and invasive flora, and a forest’s regrowth in the wake of earth disturbances such as construction activities. Made during a time of lockdown and insurrection, the works are as much depictions of place as allegories of a period that for many feels unsettled, transitory, and isolating.

In the installation “06.01.2020 18.39” (2022), Alfredo Jaar meditates on the events of June 1, 2020, six days after police officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd, a forty-six-year-old Black man. One of the many peaceful protests following Floyd’s death took place in Washington, DC’s Lafayette Square, near the White House. In order to facilitate a photo op for former President Donald Trump raising a Bible in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church adjacent to Lafayette Square, US Attorney General William Barr ordered federal forces to clear the area. They subsequently fired on the peaceful protestors with tear gas, stun grenades, and rubber bullets. They also flew two helicopters so low to the ground that the wind created by their rotors broke tree branches and scattered debris. The militarized use of helicopters has been prohibited by international human-rights law and horrified Jaar: “When, starting at 6:39 p.m., authorities set off a series of explosions in the middle of the crowd in Lafayette Square, I thought about my own experience in Pinochet’s Chile. A few hours later, I watched with horror the arrival of the helicopters. That is when I realized that I was witnessing fascism. Fascism had arrived in the USA”. Michael E. Smith works with manipulated everyday objects that he reimagines through placement and juxtaposition. Frequently precarious in condition and placed in overlooked spaces, his works evoke a variety of fragile states—physical, economic, political, and emotional. The logic of these works— an appraisal of the relationship between trash and treasure—speaks to a culture of both obscene abundance and rampant need. But Smith’s objects also teem with a sly and biting humor, a form of slapstick that uses breakdowns and stumbles to point to a culture in an ongoing state of collapse.

Participating Artists: Lisa Alvarado, Harold Ancart, Mónica Arreola, Emily Barker, Yto Barrada, Rebecca Belmore, Jonathan Berger, Nayland Blake, Cassandra Press, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Raven Chacon, Leidy Churchman, Tony Cokes, Jacky Connolly, Matt Connors, Alex Da Corte, Aria Dean, Danielle Dean, Jane Dickson, Buck Ellison, Alia Farid, Coco Fusco, Ellen Gallagher, A Gathering of the Tribes /Steve Cannon, Cy Gavin, Adam Gordon, Renée Green, Pao Houa Her, EJ Hill, Alfredo Jaar, Rindon Johnson, Ivy Kwan Arce and Julie Tolentino, Julie Tolentino; Ralph Lemon, Duane Linklater, James Little, Rick Lowe, Daniel Joseph Martinez, Dave McKenzie, Rodney McMillian, Na Mira, Alejandro “Luperca” Morales, Moved by the Motion, Terence Nance, Woody De Othello, Adam Pendleton, N. H. Pritchard, Lucy Raven, Charles Ray, Jason Rhoades, Andrew Roberts. Guadalupe Rosales, Veronica Ryan, Rose Salane, Michael E. Smith, Sable Elyse Smith, Awilda Sterling-Duprey, Rayyane Tabet, Denyse Thomasos, Trinh T. Minh-ha, Wang Shui, Eric Wesley, Dyani White Hawk and Kandis Williams

Photo: Renée Green, Space Poem #7 (Color Without Objects: Intra-Active May-Words), 2020 (Installation view, Bortolami Gallery, New York, 2020). Polyester nylon and thread, 28 double-sided banners, 42 × 32 in. (106.7 × 81.3 cm) each. Image courtesy the artist; Free Agent Media; and Bortolami Gallery, New York. Photograph by Kristian Laudrup

Info: Curators: David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards, Assistant Curators: Mia MatthiasGabriel Almeida Baroja and Margaret Kross, Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York, NY, USA, Duration: 6/4-5/9/2022, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Thu 10:30-18:00, Fri 10:20-22:00, Sat-sun 11:00-18:00, https://whitney.org

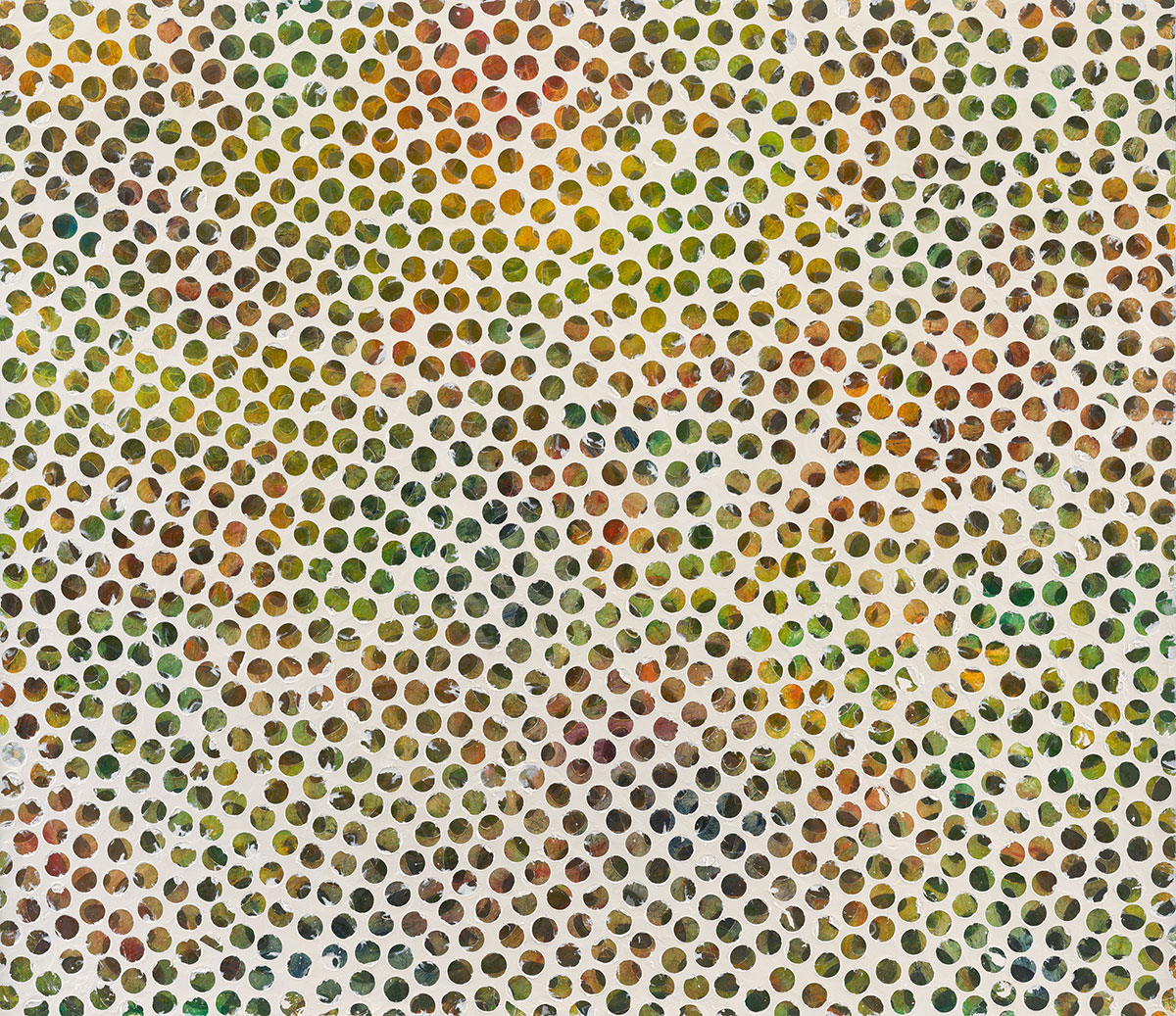

Right: Matt Connors, Body Forth, 2021. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 30 × 27 in. (76.2 × 68.6 cm). Courtesy the artist; CANADA, New York; The Modern Institute, Glasgow; Xavier Hufkens, Brussels; and Herald St, London