ARCHITECTURE: Aerodream, Part II

If the dream of flying has accompanied man since Icarus, it is really with the idea of an inflatable sheath, taking the place of the deployment of wings, that it became effective starting from the 18th century. The history of inflatables, parallel with that of aeronautics, is that of the development of a more organic relationship to the aerial. The sheath is a metaphor for the skin, a protection for the body, enabling an immediate proximity with the air. The inflatable carries within itself the idea (Part I).

If the dream of flying has accompanied man since Icarus, it is really with the idea of an inflatable sheath, taking the place of the deployment of wings, that it became effective starting from the 18th century. The history of inflatables, parallel with that of aeronautics, is that of the development of a more organic relationship to the aerial. The sheath is a metaphor for the skin, a protection for the body, enabling an immediate proximity with the air. The inflatable carries within itself the idea (Part I).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine Archive

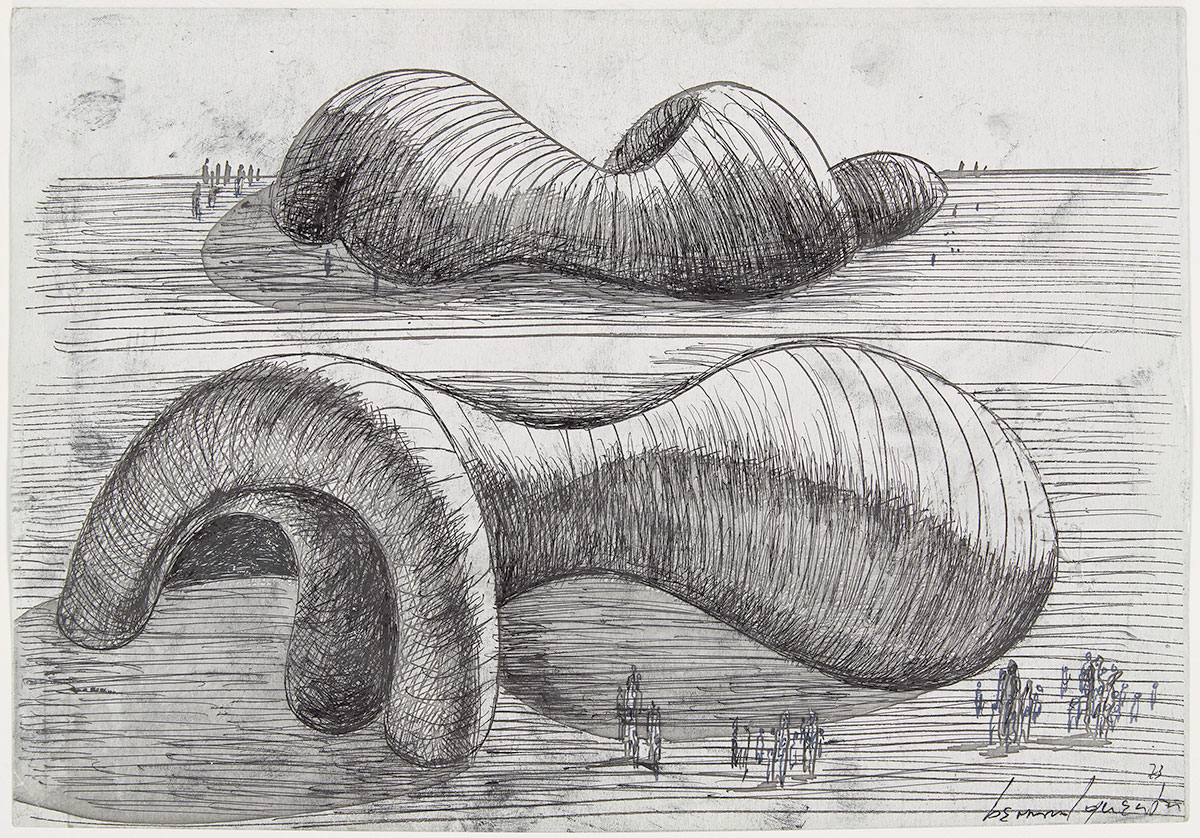

The exhibition “Aerodream. Architecture, Design & Inflatable Structures” reveals this human dimension of the «pneumatic», from the first industrial and military exploitations (airships, weather balloons, floating assemblies, inflatable decoys…) to the experiences developed by numerous artists designers and architects. In the middle of the 20th century the appearance of new materials (rubber and derivatives, plastics, woven fishnet…) multiplied the possible uses and practical applications of inflatable structures. Visitors enter a fluid space, organised into sections featuring works of art, design and architecture, accompanied by substantial documentary material. Magazines and journals, written works, posters, and photographs situate the works on display in their original contexts, together with extensive audio-visual material presenting an array of often ephemeral works, happenings and installations. Visitors are invited to discover clusters rather than sequences of works. Open vistas of the works ahead situate each section within the exhibition’s narrative, while at the same time encouraging viewers to make their own, personal connections between the works on show. Through 250 works and the presentation of monumental inflatables scattered in the permanent galleries of the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine, the exhibition strives to identify a real cultural phenomenon. Over a brief period, many creators from all disciplines seized on inflatables and pneumatic structures as a new medium, support for multiple forms of action and expression, from the design of objects to that of events. , environments, architectural and urban projects. From the mid-1960s to the beginning of the 1970s, artists, architects, engineers and designers have, through the inflatable, redefined the relationships of architecture to the foundation, to the territories, but also to the space in a new relationship to the body, thanks to multiple interventions and installations. Pneumatic forms have emerged as signs of a new way of life, often linked to social or political demands that find a broad echo in advertising and cinematographic imagery.Marcel Duchamp’s blown-glass phial of “Air de Paris” is an early use of actual air in modern art, but the inflatable proper enters the realm of art sometime later, with Piero Manzoni, whose work both critiques the art object and evokes the artist as creator, represented here solely by the force of his own breath. This organic image, a metaphor for the artist’s body, is transfigured by the members of Gruppo T, in the “Grande oggetto pneumatico”, an inflatable, interactive ‘Hydra’-like installation. Otto Piene of the ZERO group saw inflatables as a forum for exchange and interaction, in a radical re-think of the artwork’s spatial relationship to its surroundings, whether in a gallery or museum setting, or through public “actions”. The critique of the art object is expressed through the reinterpretation of abstract or minimalist works: Iain Baxter transforms works by Donald Judd and Mark Rothko into inflatables, while works by Hans Haacke, Josep Ponsatí, Christo and Panamarenko inflate until they seem to float in space. A video of Anish Kapoor’s monumental, immersive sculpture Leviathan completes the section. Installed at the Grand Palais, Paris, for Monumenta 2011, the work allowed visitors to step inside it and walk about, drowning in color. The Montgolfier brothers rose to great heights in the 18th century, but it was not until the 1870s that the industrial potential of inflatable structures was exploited, when the photographer Nadar used balloons to facilitate military observations in the Franco-Prussian war. Their use became widespread, leading to the creation of aerostats (giant static balloons), dirigibles or ‘blimps’ and airships. The Hindenburg disaster in 1937 brought the era of commercial airship flights to an end. Similarly, the innovations of Dunlop, Goodyear and Michelin (the first businesses to make rubber tyres) lead to a wealth of new applications, from inflatable objects to military and industrial structures (inflatable decoy tanks, cannons, trucks and boats), and works of civil or military engineering (bridges, barrages, hangars and warehouses). Inflatable structures began to be widely used in architecture: pioneering architects such as Franck Lloyd Wright and Richard Buckminster Fuller produced designs for often large-scale urban buildings free of foundations. In the 1960s, inflatables were widely used in industry, by developers and engineers such as Walter Bird, Frei Otto, Victor Lund, and Cedric Price – pioneers who presented their work at foundational conferences, beginning with Stuttgart in 1967.

Architects working with inflatable structures – notably Cedric Price, and Johanne and Gernot Nalbach – sparked a body of utopian and critical research on ‘pneumatic’ architecture. In England, Arthur Quarmby designed a pneumatic structure for Brighton Marina, and an inflatable dome for director Robert Freeman’s 1968 film “The Touchables”. The Archigram group designed the “Instant City” and the Cushicle, imaginative, visionary works that defined a new relationship between the human body, living space and the city. Numerous artists and architects used inflatable forms as a critical and forward-thinking medium, but it was thanks to three large-scale exhibitions that they achieved widespread public and political recognition. Inflatable structures staged by the Utopie group in Paris, connected industrial research with creative experiments from a new generation of artists and designers. The show became a manifesto for the medium and achieved instant international acclaim. Among the featured artists, Bernard Quentin was notable for his use of inflatables in design, architecture and visual art. Expo ’70 in Osaka (1970) provided an international showcase for inflatable structures, with several pavilions (the Fuji Group, Yutaka Murata’s “Floating Theatre”, Taneo Oki’s “Mushballoon” and others), together with several pneumatic architectural projects that were never realised, but were widely published nonetheless. Documenta 4 in Kassel (1968) featured interventions by Christo and Walter Pichler, while documenta 5 (1972) established inflatables as a mainstream medium, with Haus-Rucker-Co’s celebrated “Oase Nr7” and “The Aeromodeller” by Panamarenko. Numerous, early architectural interventions in the urban space focused on the individual human body: architects ran, worked, cocooned and relaxed in ‘bubble’ environments (Hans Hollein’s “Mobiles Bür”o, the “Unruhige “ by Coop Himmelb(l)au, or Mark Fisher’s “Inflatable Body Suit”). More large-scale installations invited the public to experience pneumatic spaces through play, or simply by traversing them on foot (Haus – Rucker – Co’s “Giant Billiard”, or the “Waterwalk Tube” by the Eventstructure Research Group). Each new creation offered unprecedented, alternative ways to experience and apprehend the urban environment, through the use of inflatable structures. The ecological dimension of inflatables was forcefully established by works such as Graham Stevens’s “Desert Cloud”, for the 1970 Earth Day event in New York, and the “Air Dome” by Yukihisa Isobe.

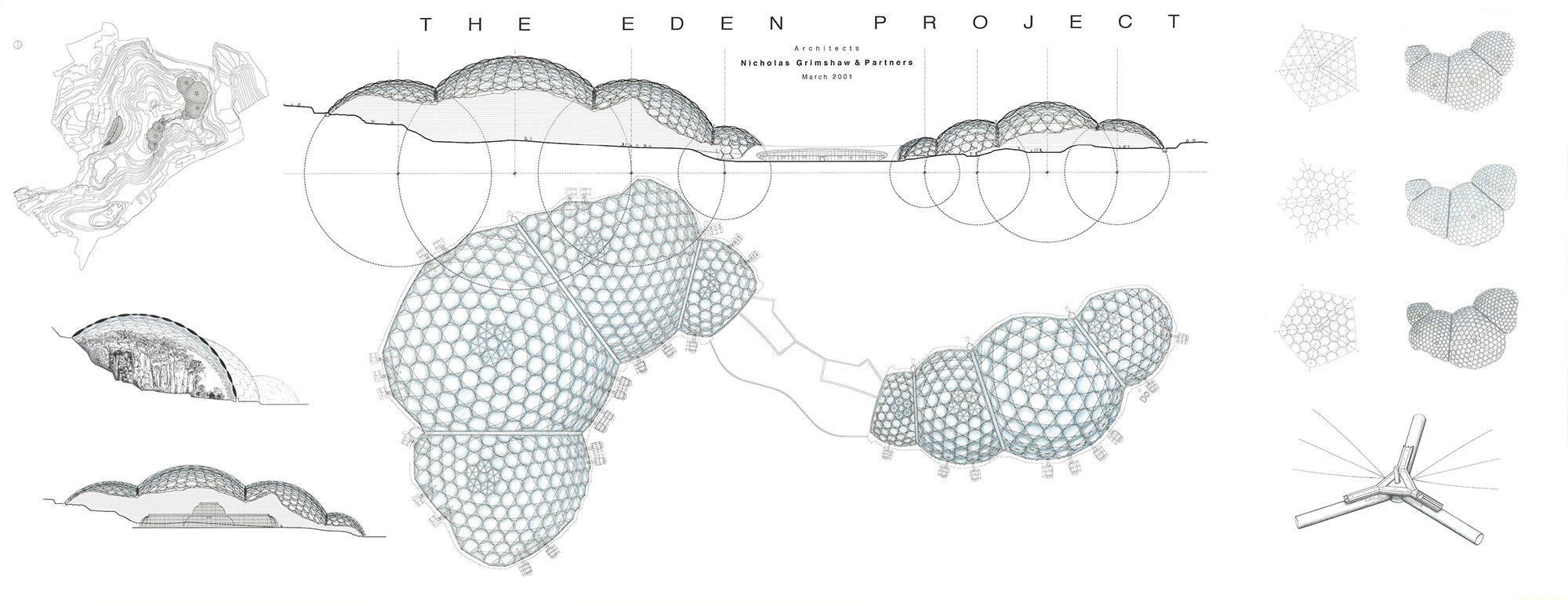

The universal availability and use of plastic enabled numerous designers to create furniture in a wide array of shapes and colors reflecting the Pop Art imagery of the 1960s and 70s. Quasar Khanh’s “Aerospace collection” established him as the most prolific and wide-ranging designer in the form, creating everything from mobile partitions to lamps and even an inflatable house. A.J.S. Aérolande created modular furniture based on simple elements (cushions, tubes assembled to form seats, banquettes, sofas) while other designers issued occasional or one-off pieces – the “Blow armchair” by De Pas, D’Urbino & Lomazzi, or Verner Panton’s “Inflatable Stool”. The oil crisis of the 1970s curtailed the industrial use of plastics, and inflatables lost their appeal. The advent of post-modernism favored a return to more traditional modes of construction. But since 2000, architects have revisited pneumatic architectural forms, using new materials to create ephemeral projects, installations and large-sale amenities. Kengo Kuma has created a dedicated space for the Japanese tea ceremony, while Selgascano and Snøhetta create ‘signal’ architectural spaces for temporary public pavilions. Diller Scofidio and Renfro designed an inflatable extension for the Hirshhorn Museum, and Anish Kapoor has conceived a genuinely mobile performance space in association with Arata Isozaki. Other architects use inflatable technology for large-scale projects, reconnecting with the aspirations of the pioneers of pneumatic architecture such as Frei Otto. Rem Koolhaas and Cecil Balmond designed the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, Herzog & de Meuron created Munich’s Allianz Arena, and Atelier Zündel Cristea – AZC have proposed an inflatable bridge over the Seine, Paris.

Photo: Yutaka Murata, Fuji Group Pavilion, Osaka, 1970, © Yutaka Murata, © Osaka Prefectural Expo 1970 Commemorative Park Office

Info: Curators: Frédéric Migayrou and Valentina Moimas, Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine, 1 Place du Trocadéro et du 11 Novembre, Paris, France, Duration: 6/10/2021-14/2/2022, Days & Hours: Mon-Wed & Fri-sun 11:00-19:00, Thu 11:00-21:00, www.citedelarchitecture.fr

Right: Haus-Rucker-Co, Mindexpander 1, 1967, © Centre Pompidou MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-GP/Georges Meguerditchian, © Haus-Rucker-Co