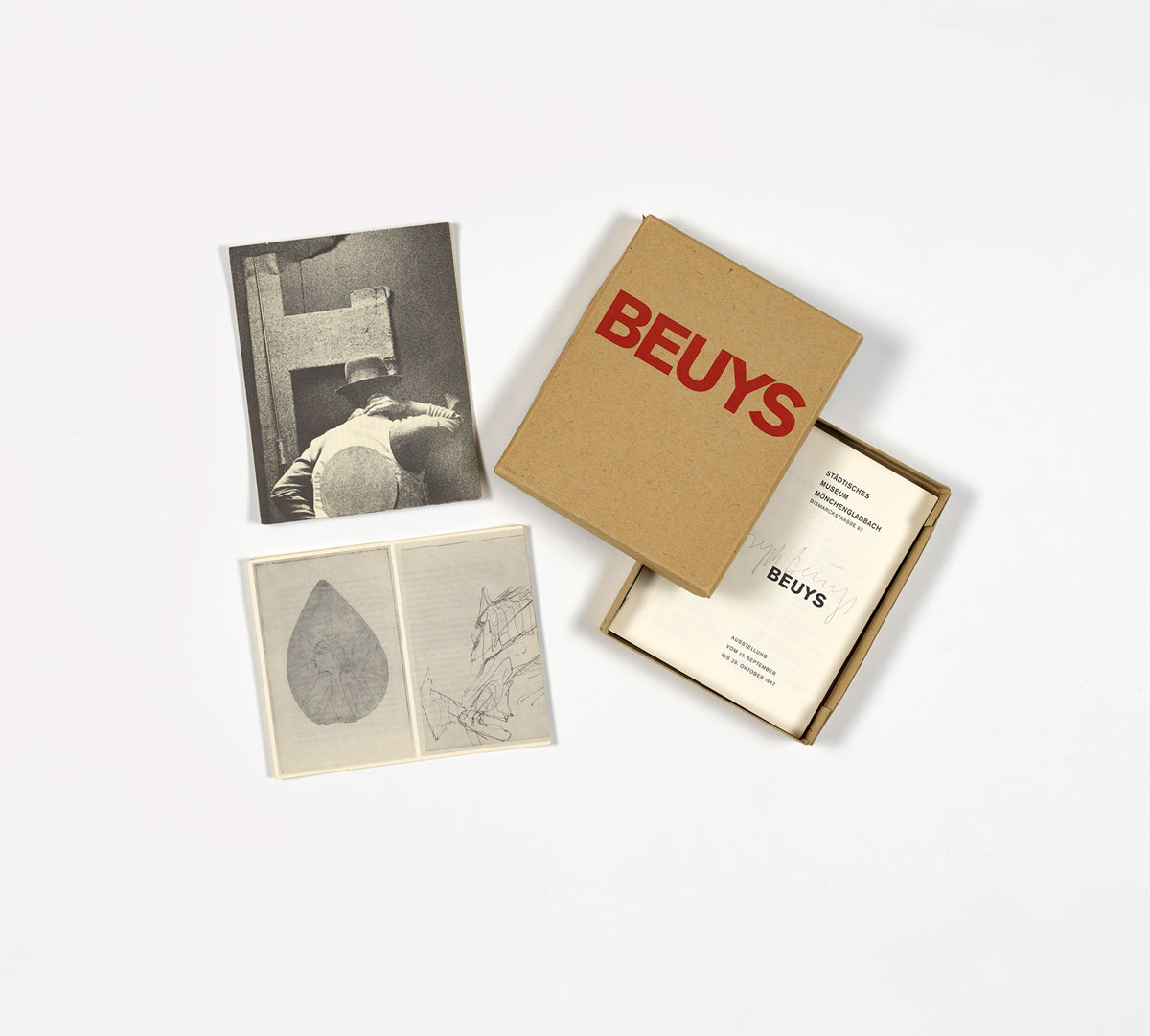

ART-PRESENTATION: Joseph Beuys-Think. Act. Convey.

Marking the centenary of Joseph Beuys’ birth, 2021 will see over 30 museum exhibitions taking place internationally in Europe, America and Asia.This year’s centenary programme celebrates Joseph Beuys’ life and work through curatorial approaches that consider his extensive oeuvre anew. Emerging as an artist in the midst of post-war German reconstruction, he claimed a unique role for art in the spiritual renewal of society, profoundly changing and expanding the prevailing concept of art. His enduring influence as a creative force has shaped and continues to inspire the art world and contemporary artistic practice.

Marking the centenary of Joseph Beuys’ birth, 2021 will see over 30 museum exhibitions taking place internationally in Europe, America and Asia.This year’s centenary programme celebrates Joseph Beuys’ life and work through curatorial approaches that consider his extensive oeuvre anew. Emerging as an artist in the midst of post-war German reconstruction, he claimed a unique role for art in the spiritual renewal of society, profoundly changing and expanding the prevailing concept of art. His enduring influence as a creative force has shaped and continues to inspire the art world and contemporary artistic practice.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Belvedere 21 Archive

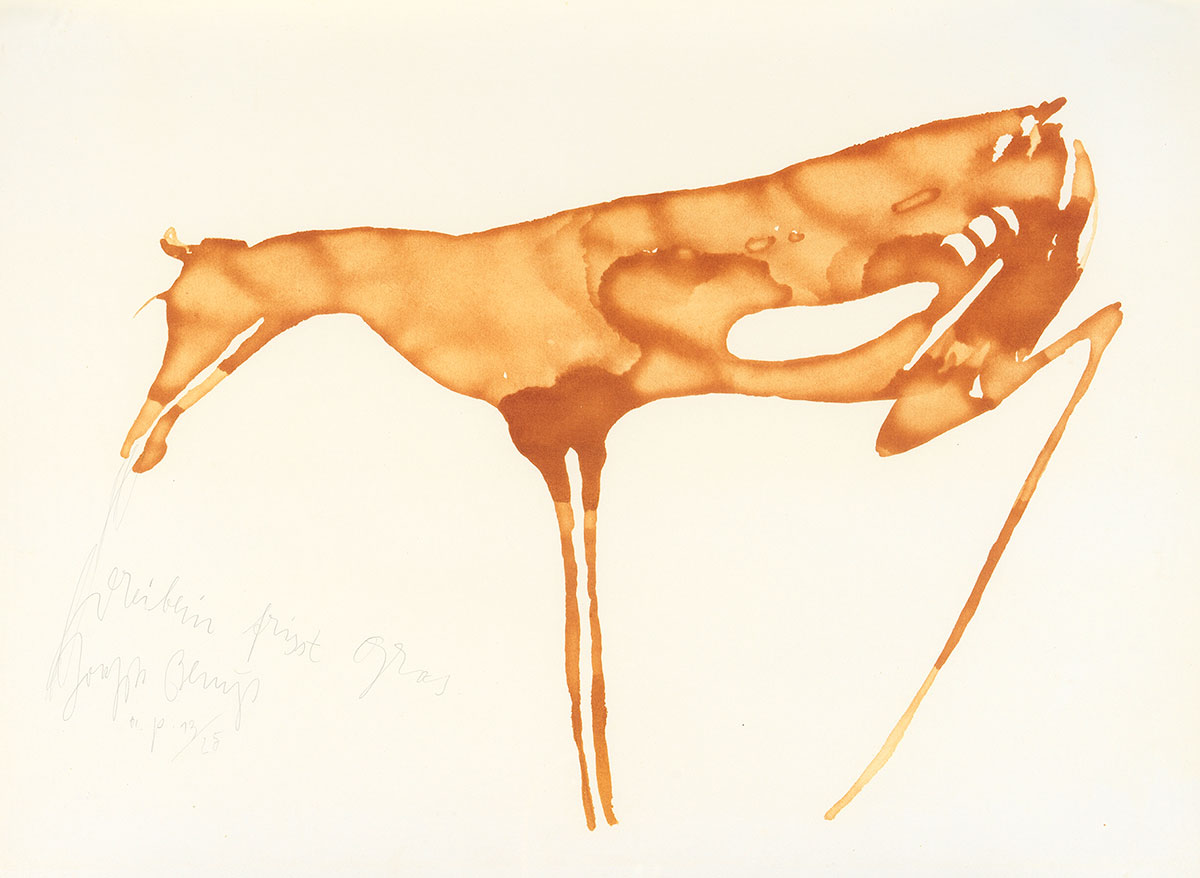

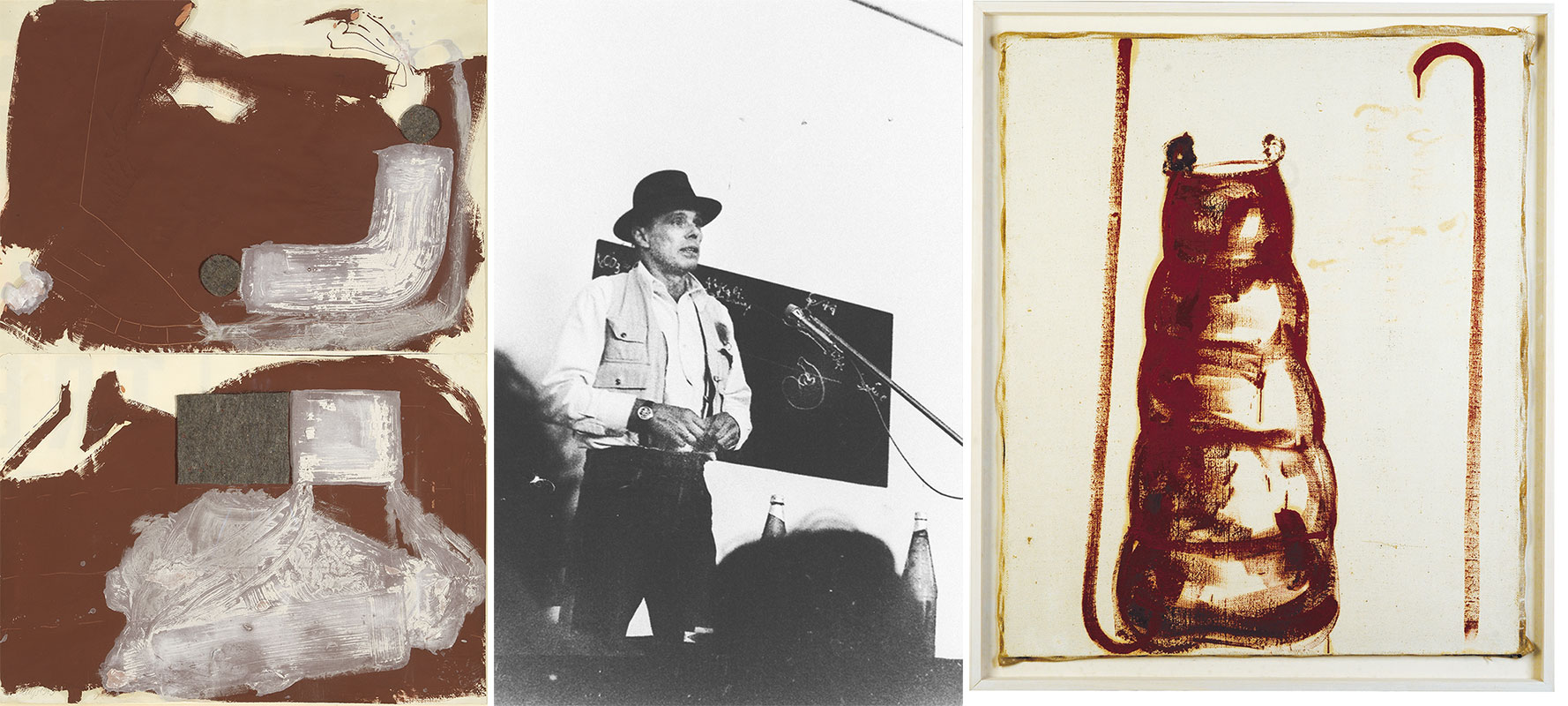

The first major museum exhibition “Joseph Beuys: Think. Act. Convey.”, focuses on the concepts underlying his artistic philosophy and actions. Beginning in the 1960s, Joseph Beuys developed new modes of thought that, in their complexity, continue to be relevant today. He achieved universal fame with his expanded definition of art and the concept of social sculpture. Art, according to Beuys’ guiding principle, is meant to assert itself on the social, political, intellectual, and scientific level and thus become an integral part of our mindset and actions. On the centenary of the exceptional artist’s birth, his work is more relevant than ever. The presentation also revolves around the concepts of thinking, acting, and mediating: While the main work, “Honey Pump at the Workplace” (1974-77) stands as a symbolic representation of Joseph Beuys’ creed that societal transformation can be achieved through art, “Stag Monuments” (1958-85) seemingly marks the new beginning of a shattered society. Since childhood, Beuys had been interested in northern European folklore, in which certain animals are endowed with mystical power. The stag had particular significance for him as the mythical guardian of the forest. The yearly shedding and regrowth of its antlers were a potent symbol of rebirth and renewal. In this work Beuys brings together iron, whose cold strength and durability he associated with masculinity and war, with copper, one of the softest metals which he associated with femininity. In addition, the exhibition also embraces works and documentation of Beuys’ work in Vienna. Beuys took part in exhibitions, actions, and lectures in the city – mainly the Galerie nächst St. Stephan. He developed for this gallery, among other things, the environment “Basisraum Nasse Wäsche” (1979). This environment was created in answer to a question that Beuys was asked about the former Museum of Modern Art housed in the Palais Lichtenstein in Vienna. Asked for his opinion of the exhibition space provided there, Beuys replied that it was fit only for hanging up wet laundry. The work is a polemic against the dominant feudal Baroque architecture, whose suitability as an exhibition venue was frequently in doubt. The original idea called for dripping wet laundry to be left for years to rot on the floors of the sumptuously ornate rooms. The aim was to instigate a kind of cleansing ritual that would highlight the historic distance between the present and the obsolete feudal view of the world represented by the palace. The subsequent addition of guttering to the installation broadened the setting on grounds of presentational necessity; the table and chair imply a working atmosphere and perhaps provide the visitor with an opportunity for reflection within the installation. The materials evoke associations that are also motivated by mythology or by individual (or collective) history and experience. The soap that binds together the heaps of washing, for example, is a cleansing agent with compulsive connotations. Its material characteristics are unifying and binding, even though it is manufactured chemically out of its antithesis, namely fat. The individual elements in the work thus act as a catalyst for thought processes and political empowerment. Beuys wanted the installation’s complex historical and personal allusions and readings to generate scope for autonomous thought and action based on the viewers’ cognitive skills. Collaborating with Oswald Oberhuber and the University of Applied Arts, where he taught as a guest lecturer in 1980, Beuys orchestrated the planting of trees for his global action 7000 Oaks in 1983. In the exhibition, we find the sculptural as a vestige of the action, in form of a documentary or as a “multiple.” The performance “Eurasienstab 82 min fluxorum organum”, in 9/2/1968, Joseph Beuys’ and musician Henning Christiansen’s iconic action took place at Wide White Space gallery in Antwerp, where it was also recorded on 16mm film. Beuys performs a ritual for symbolically reuniting the four winds of Eurasia, seeking to reconcile Asian spirituality with European rationality. To bring these seemingly opposing energies in balance he uses the Eurasienstab, a long staff made of copper. The staff, used by the priest, the shepherd and the shaman alike, is a recurring motif in Beuys’ work, and occasionally with a walking stick as a surrogate.

The action “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare” was a solo performance by Beuys, who was filmed and photographed for three hours as he moved through the Schmela Gallery exhibition with the carcass of a hare, whispering inaudibly to it. His entire head was covered in honey and gold leaf; a felt sole was tied to his left foot, and an iron sole was tied to his right. The Action ended with Beuys seated on a stool with one of its legs wrapped in felt (a bone and wire ‘radio’ was placed underneath the seat), protectively cradling the deceased hare in a manner akin to the Madonna in a pietà. Beuys covered his head with honey –(a nurturing substance unique to the creative powers of bees) in order symbolically to associate the bee’s capacities with his own efforts to expand the human potential for thought and expression beyond the rational. The gold flakes called attention to Beuys’s role as a life-giving artist whose ‘artistry’, like that of the bee, was analogous to the sun’s radiant, all-encompassing powers. The application also intensified the ritualistic tenor of the performance by masking Beuys’s features, in keeping with his intermediary role as shamanistic medium in communication with the hare’s spirit-being. The hare, according to Beuys, stood in for our “deadening” intellectualizing tendencies to burrow (metaphorically) into the ‘materialistic’. However, the hare’s ability to transform the earth into a habitat that accorded with its body shape was also a creative act. The long-running performance “I Like America and America Likes Me” (1974) convey the spirit of that time. Beuys arrived in New York City, ready to tackle a whole new challenge and create what was to become one of the most famous works of art of the time. Upon arrival, his assistants wrapped him in a large piece of felt and transported him, by ambulance, to the René Block Gallery in SoHo. There, awaiting the artist, was a live coyote. Beuys spent three consecutive days, eight hours at a time, locked up with the wild animal. He sat or stood, wrapped from head to toe in his large felt cover and held a crooked staff, peeking out from the top of the felt. Accompanying him in the cage included heaps of straw, a pile of copies of The Wall Street Journal of the day and a raggedy old hat from the best hat shop in London. Then, of course, there was his co-star, the coyote. Beuys’ idea behind “I Like America and America Likes Me” was to start a national dialogue. America in the 1970s, caught in the horrors of the Vietnam war, and divided by oppression of minorities, the indigenous population and immigrants, was far from the welcoming American Dream that the title of this performance suggests. The coyote symbolised a variety of things for Beuys: First, there are some Native American myths that suggest that the coyote represents the possibility for transformation, as well as an archetypal trickster. Then, there are certain creation myths in which the coyote teaches human beings how to survive. And while most European settlers and their present-day American descendents generally regarded the coyote as an aggressive and dangerous predator, Beuys saw the animal as something completely different: to him, it was America’s spirit animal. When it was over, he was bundled up again, returned to the ambulance, and driven straight back to the airport. He never once set foot on American soil, except for the gallery space. He wanted the only ground he touched in America to be the ground he shared with the coyote. With this intense performance, Beuys wanted to demonstrate that American society could only start to heal its social issues through communication, connection and mutual understanding between all of America’s vastly different social groups.

Photo: Joseph Beuys, tree planting in the garden and in front of the University of Applied Arts, 1983, University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection and Archive, Inv.No. 16.102 / 1 / FP / Photo: Philippe Dutartre

Info: Curator: Harald Krejci, Belvedere 21, Arsenalstraße 1, Vienna, Duration: 4/3-13/6/2021, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 11:00-18:00, www.belvedere.at

Center: Joseph Beuys during his lecture at Galerie nächst St. Stephan on April 4, 1979, Photo: Gerhard Kaiser, Gerhard Kaiser Archive

Right: Joseph Beuys, Untitled (Friedrichshof), 1983, Private Collection / Bildrecht, Vienna 2021