GREAT MUSEUMS:MoMA Collection Highlights 2020-2021

The new MoMA opened on 21/10/2019, with an innovative collection model that highlights the creative affinities and frictions produced by displaying painting, sculpture, architecture, design, photography, media, performance, film, and works on paper together. The majority of MoMA’s collection galleries now feature works from two or more of the Museum’s curatorial departments, proceeding along a broadly chronological spine. A selection of medium-specific galleries within each circuit delves into art and ideas.

The new MoMA opened on 21/10/2019, with an innovative collection model that highlights the creative affinities and frictions produced by displaying painting, sculpture, architecture, design, photography, media, performance, film, and works on paper together. The majority of MoMA’s collection galleries now feature works from two or more of the Museum’s curatorial departments, proceeding along a broadly chronological spine. A selection of medium-specific galleries within each circuit delves into art and ideas.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MoMA Archive

Recognizing that there is no single or complete history of modern and contemporary art, each floor of galleries offers a deeper experience of art through all mediums and by artists from more diverse geographies and backgrounds than ever before in an exhibition divided in three sections: “1880s–1940”, 1940–1970 and 1970–Present.

Some of the subsections are: New York City 1920s highlights the exuberant cultural transformations of New York City in the 1920s. Whether the artists were inspired by their dynamic and ever- changing urban surroundings or by the potential to articulate new art, the vibrancy of the New York art scene is evident in Stuart Davis’s “Lucky Strike” (1921), Aaron Douglas’s “Study for the cover of God’s Trombones” by James Weldon Johnson (1926), and Georgia O’Keeffe’s “Abstraction Blue” (1927). Mediums like photography and film gained widespread popularity and offered different possibilities for representation. Galleries, art schools, and newly established art institutions in the city became nexus points for artists from downtown to Harlem, showing the complexity and breadth of New York’s burgeoning artistic scene in the interwar years and providing inspiration to the likes of James L. Wells, Peter Blume, and José Clemente Orozco.

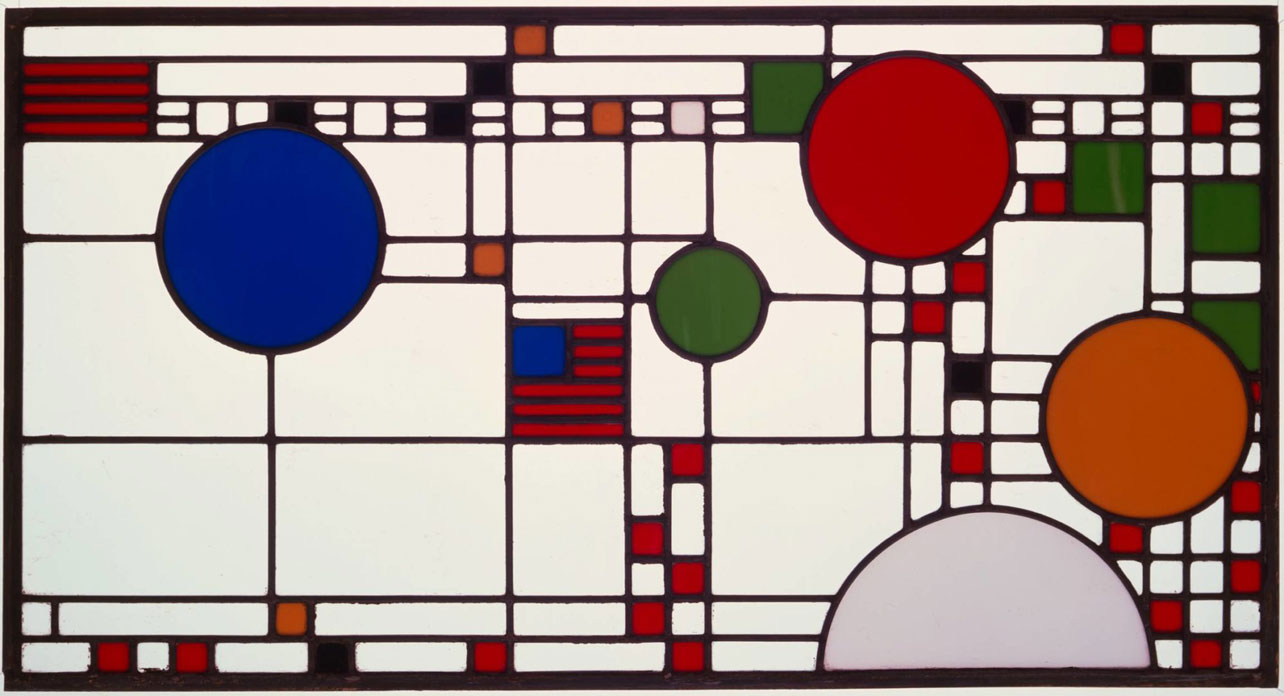

Ornament and Abstraction explores the origins of architectural abstraction in both geometric and natural ornament. This gallery features the work of architects in both the US and Europe in the decades on either side of 1900. Key pieces from MoMA’s collection by Theo van Doesburg, Louis Sullivan and Hans Poelzig, among others, are considered alongside drawings and architectural fragments by Frank Lloyd Wright, whose work during this period explored nature and geometry as a path to invention.

Gerhard Richter’s “October 18, 1977”, a 15-painting cycle, takes as its chief subject the arrests and deaths of key members of the Red Army Faction (RAF), a radical left- wing organization that led a years-long campaign of violence against the West German government. Made more than a decade after the events pictured, Richter’s paintings are based on photographs found in media coverage as well as in government archives. The series (a contemporary take on the centuries-old tradition of history painting) does not set forth a judgment or viewpoint on the chronicled events, but offers them up as a subject for reflection and remembrance.

Gordon Parks and “The Atmosphere of Crime” (Gallery draws its title from Parks’s groundbreaking photo-essay, published in Life magazine on 9/11/1957. Anchored by a recent major acquisition from this unforgettable series, this installation probes representations of crime in photography. Parks’s evocative color prints are contextualized with 19th-century work, including mugshots, and a generous selection of crime photographs from the New York Times Collection, as well as a clip from Parks’s legendary 1971 film “Shaft”. The gallery groups together a complex history of capturing criminality, its intersection with race, and its representation in the US.

Domestic Disruption highlights the work of artists Marisol, Martha Rosler, Ed Ruscha, and Betye Saar, who, in the 1960s, began to focus on everyday objects as forms for inspiration, contemplation, and subversion. Strategies run the gamut, from inflating small objects into enormous versions of themselves, to committing the fleeting to permanence, to turning familiar items strange. Tom Wesselmann’s “Still Life #57” (1969–70) a radically different side of Wesselmann’s work and one that playfully reconsiders the world is on view among these works and for the first time in MoMA’s galleries since 1971.

The Sum of All Parts looks at the relationship and often, misfit between the individual and sociopolitical structures that was a central concern for artists around the world during the 1980s. Their work often touched on major public debates on pressing social issues, including the AIDS crisis, reproductive rights, and racism. The artists in this gallery invoke the human body (both as a physical entity and as a complex symbolic terrain) to address matters of self-enlightenment, trauma, anti-racism, and social justice. Working across a range of mediums, they deploy personal reflection as a means of underscoring how the experiences of the individual and that of their broader community are inevitably bound together, hinting at the potential for collective action.

Carrie Mae Weems’s “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried” is presented as a full-gallery installation and reveals, in the artist’s own words, “the ways in which Anglo America—white America—saw itself in relationship to the black subject”. The work (1995–96) is comprised of appropriated 19th- and early-20th-century images featuring African Americans, including distressing daguerreotypes of slaves in the American South taken by photographer Joseph T. Zealy in 1850. Commissioned by the Harvard scientist Louis Agassiz, Zealy’s images were meant to support societal preconceptions and racist theories about the inferiority of Black people. Many of the sitters are naked or half naked and depicted as anthropological specimens rather than individuals. The work is bookended by images of a royal Mangbetu woman witnessing the narrative. Through her presentation, Weems asks us to question the intentions behind these pictures and their dissemination. She enlarged, cropped, and tinted the images, then placed the prints in circular mattes that suggest the camera’s lens, emphasizing the acts of framing and looking. Finally, she overlaid the images with her own texts, which expose a long history of systemic injustice.

Nam June Paik, Instant Zen: Nam June Paik worked across a range of mediums, including mail art, film, sculpture, and performance, enthusiastically pushing back against the categories and boundaries of art. His distaste for established conventions was reflected in the humor with which he approached emerging media technology. In his long-standing relationship with Fluxus he found a community that shared this attitude and approach. Many of the works in this gallery explore chance, silence, nothingness, and the beauty of gradual change over time. They attest to the influence of the ideas of John Cage and Eastern philosophy on Paik and his Fluxus peers and embrace unpredictability by inviting audience participation. For other works, Paik modified found objects such as toy trucks or clocks, extending Marcel Duchamp’s early-twentieth-century concept of the readymade: a mass-produced object removed from its intended context and presented as art.

Print, Fold, Send: In the 1970s and 1980s, while new technologies aided the unprecedented global circulation of goods and information, artists and activists across Latin America turned to do-it-yourself and “lo-fi” means to disseminate their own work. They sent art by mail, produced zines and pamphlets, and founded small presses. These systems and platforms allowed them to produce works that could be distributed easily, avoiding the commercial structures of the art world and the policing of repressive political regimes. Interested in communications technologies, many of these artists also explored the new potential of video and other electronic media, whether through art made for cable networks, interventions in TV programs, or works for Minitel technology. They helped form a burgeoning global community of artists whose work took place outside the protocols of formal institutions and traditional media. However, the results of these alternative approaches entered established art institutions in unexpected ways: for example, by being mailed directly to MoMA’s library, as was the case with many of the print works in this gallery.

Cao Fei’s Whose Utopia: Cao Fei illuminates the human workforce behind one of the largest manufacturers of light bulbs in the world. Consisting of three parts, this video was shot during a six-month residency the artist participated in at the OSRAM lighting factory in the Pearl River Delta region of China. She not only documented the factory’s production processes but also collaborated with workers to develop performances that were staged throughout the facility. During their performances, some of the factory employees wear regular clothing, while others choose to wear costumes; some dance while others play guitar. These moments transform a space in which movement is highly controlled into one that allows for fluidity, play, and self-expression. It is possible that some of the lights made at this factory are currently illuminating the city beyond this gallery—where other workers are busy with their own routines.

Photo: Kiki Smith. Untitled. 1987-90. Silvered glass water bottles, Each bottle 20 1/2″ (52.1 cm) x 11 1/2″ (29.2 cm) in diameter. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Louis and Bessie Adler Foundation, Inc.

Info: The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), 11 West 53 Street, Manhattan, New York, Duration: 14/11/2020-Summer 2021, Days & Hours: Daily 10:30-17:30, www.moma.org

Right: Barbara Chase-Riboud. The Albino. 1972 (reinstalled in 1994 by the artist as All That Rises Must Converge/Black). Bronze with black patina, wool and other fibers. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Right: Carrie Mae Weems. You Became Mammie, Mama, Mother & Then, Yes, Confidant-Ha from From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried 1995-96. Chromogenic color print with sand-blasted text on glass, 26 3/4 × 22″ (67.9 × 55.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift on behalf of The Friends of Education of The Museum of Modern Art

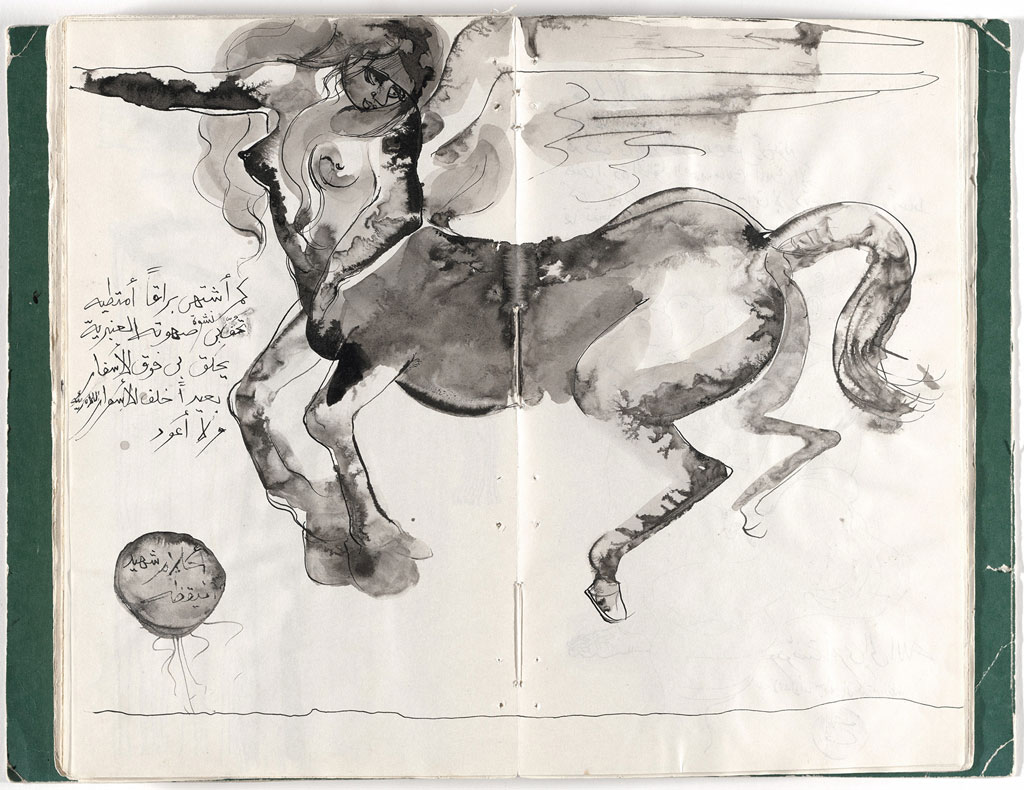

Ibrahim El-Salahi. Prison Notebook. 1976. Notebook with 38 ink on paper drawings. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

G. W. Bitzer. Interior N.Y. Subway, 14th Street to 42nd Street. 1905. 35mm film (black and white, silent). The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Wu Tsang. We hold where study. 2017. Two-channel video (color, sound; 18:56 min.). The Modern Women’s Fund.© 2019 Wu Tsang

Right: Gordon Parks. Untitled, Chicago, Illinois. 1957. Pigmented inkjet print, 18 × 12 1/8″ (45.7 × 30.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Gordon Parks Foundation