ARCHITECTURE: Elizabeth Diller

Elizabeth Diller (17/6/1954- ) is a founding partner of Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), a design studio whose practice spans the fields of architecture, urban design, installation art, multi-media performance, digital media, and print. Diller and co-founding partner, Ricardo Scofidiohave been distinguished with Time Magazine’s “100 Most Influential People” list and the first MacArthur Foundation fellowship awarded in the field of architecture.

Elizabeth Diller (17/6/1954- ) is a founding partner of Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), a design studio whose practice spans the fields of architecture, urban design, installation art, multi-media performance, digital media, and print. Diller and co-founding partner, Ricardo Scofidiohave been distinguished with Time Magazine’s “100 Most Influential People” list and the first MacArthur Foundation fellowship awarded in the field of architecture.

By Efi Michalarou

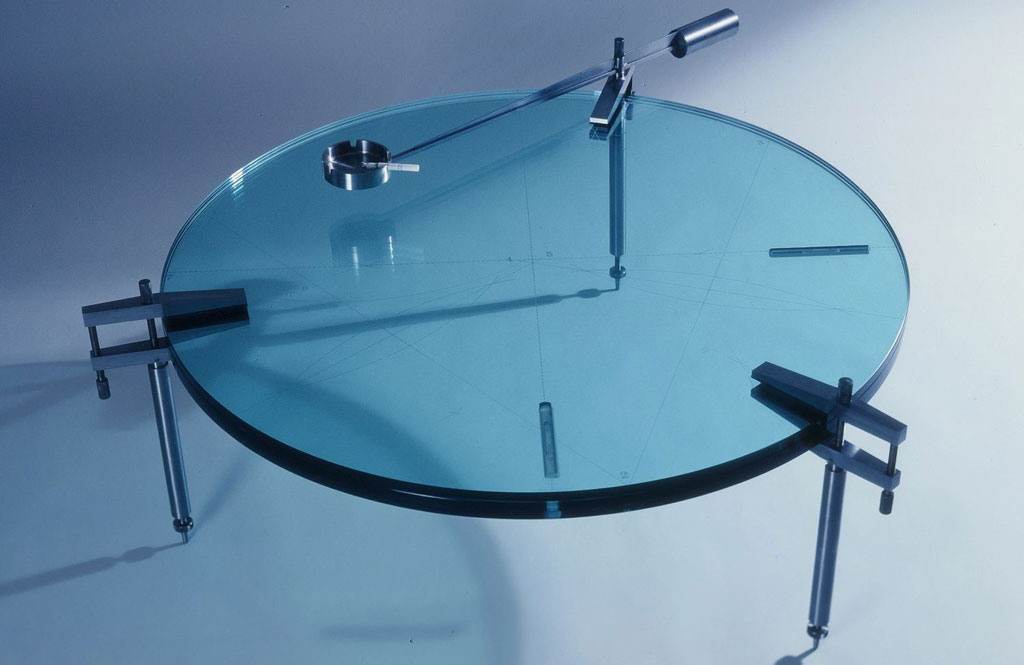

Elizabeth Diller was born in Łódź, Poland, to Jewish parents. The family emigrated to the United States when in 1960 when she was six years old. Both Diller and Scofidio studied at New York City’s Cooper Union. Ricardo Scofidio was a student in the Cooper Union School of Architecture from 1952–55, but earned his undergraduate degree from Columbia University’s architecture school in 1960. He began his career in traditional architecture firms after graduation, and became a professor of architecture at Cooper Union in 1965. It was there that they met when Diller began studying at Cooper Union’s School of Architecture in the 1970s. She originally began her studies at Cooper Union in art, but took an architecture class because she was interested in ideas about space and culture, two concepts that would be central to her work with Scofidio. While Diller was Scofidio’s student, he was already married, though he later divorced his wife. The pair did not date nor marry until after she graduated from Cooper Union in 1979. After she graduated, she began teaching at Cooper Union as an assistant professor beginning in the early 1980s. She later lectured at Harvard University, and beginning in 1990, was an associate professor at Princeton University. By this time, Diller and Scofidio were firmly established architects in their own right as Diller + Scofidio. The couple began working together in 1979. Many of their early works were rather small, and included stage sets, site–specific art installations, and performance pieces. They were already using space and form to explore social behavior. Some of their early works were very simple. In 1981, for example, Diller + Scofidio put 2,500 orange cones in New York City’s Columbus Circle for 24 hours to show traffic patterns. Three years later, the pair designed a new entrance gate, sign, and pole–based windsocks for the site of the annual Art on the Beach, a sculpture show in New York City. Diller herself had previously designed part of the set for a participatory work of art at the 1983 Art on the Beach called “Civic Plots” with sculptor James Aholl and performance artist Kaylynn Sullivan. Other early works of Diller + Scofidio’s were also related to performance and art space. In 1986, the pair provided the stage design for a performance piece called “The Rotary Notary and His Hot Plate, or a Delay in Glass”. The theater troupe Creation Production Company staged “The Rotary Notary and His Hot Plate” and the rest of the title referred to the staging which was inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s work “The Large Glass” which was originally done on a window. Diller + Scofidio put a large mirror angled on the divided stage. The actors behind a divider could be seen by the audience in the mirror. Ten years later, the pair did a set for the Charleroi/Dances Troupe’s performance called “Moving Targets” that used a mirror in similar fashion. It featured a mirror angled over the stage giving the audience an unusual view of the dancers and the stage. On a completely different front, Diller + Scofidio did “The WithDrawing Room” with sculptor David Ireland. They took a house in San Francisco, California, and transformed it into a gallery/studio as well as a work of art that commented on domestic ideas. One of Diller + Scofidio’s first important commissions was a piece at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1989 called “Para–Site”. The multi–media work was unusual in that nothing touched the floor—everything was hanging from the walls or ceiling. Para–Site” featured a number of high–tech gadgets including live video cameras, monitors, mirrors, and chairs, as well as a hole in the wall that showed plumbing and wiring. The cameras were set to capture images from other parts of the building, including the museum’s escalators, as a comment on the nature of modern society. Critics gave the project cautious praise.

Elizabeth Diller was born in Łódź, Poland, to Jewish parents. The family emigrated to the United States when in 1960 when she was six years old. Both Diller and Scofidio studied at New York City’s Cooper Union. Ricardo Scofidio was a student in the Cooper Union School of Architecture from 1952–55, but earned his undergraduate degree from Columbia University’s architecture school in 1960. He began his career in traditional architecture firms after graduation, and became a professor of architecture at Cooper Union in 1965. It was there that they met when Diller began studying at Cooper Union’s School of Architecture in the 1970s. She originally began her studies at Cooper Union in art, but took an architecture class because she was interested in ideas about space and culture, two concepts that would be central to her work with Scofidio. While Diller was Scofidio’s student, he was already married, though he later divorced his wife. The pair did not date nor marry until after she graduated from Cooper Union in 1979. After she graduated, she began teaching at Cooper Union as an assistant professor beginning in the early 1980s. She later lectured at Harvard University, and beginning in 1990, was an associate professor at Princeton University. By this time, Diller and Scofidio were firmly established architects in their own right as Diller + Scofidio. The couple began working together in 1979. Many of their early works were rather small, and included stage sets, site–specific art installations, and performance pieces. They were already using space and form to explore social behavior. Some of their early works were very simple. In 1981, for example, Diller + Scofidio put 2,500 orange cones in New York City’s Columbus Circle for 24 hours to show traffic patterns. Three years later, the pair designed a new entrance gate, sign, and pole–based windsocks for the site of the annual Art on the Beach, a sculpture show in New York City. Diller herself had previously designed part of the set for a participatory work of art at the 1983 Art on the Beach called “Civic Plots” with sculptor James Aholl and performance artist Kaylynn Sullivan. Other early works of Diller + Scofidio’s were also related to performance and art space. In 1986, the pair provided the stage design for a performance piece called “The Rotary Notary and His Hot Plate, or a Delay in Glass”. The theater troupe Creation Production Company staged “The Rotary Notary and His Hot Plate” and the rest of the title referred to the staging which was inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s work “The Large Glass” which was originally done on a window. Diller + Scofidio put a large mirror angled on the divided stage. The actors behind a divider could be seen by the audience in the mirror. Ten years later, the pair did a set for the Charleroi/Dances Troupe’s performance called “Moving Targets” that used a mirror in similar fashion. It featured a mirror angled over the stage giving the audience an unusual view of the dancers and the stage. On a completely different front, Diller + Scofidio did “The WithDrawing Room” with sculptor David Ireland. They took a house in San Francisco, California, and transformed it into a gallery/studio as well as a work of art that commented on domestic ideas. One of Diller + Scofidio’s first important commissions was a piece at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1989 called “Para–Site”. The multi–media work was unusual in that nothing touched the floor—everything was hanging from the walls or ceiling. Para–Site” featured a number of high–tech gadgets including live video cameras, monitors, mirrors, and chairs, as well as a hole in the wall that showed plumbing and wiring. The cameras were set to capture images from other parts of the building, including the museum’s escalators, as a comment on the nature of modern society. Critics gave the project cautious praise.

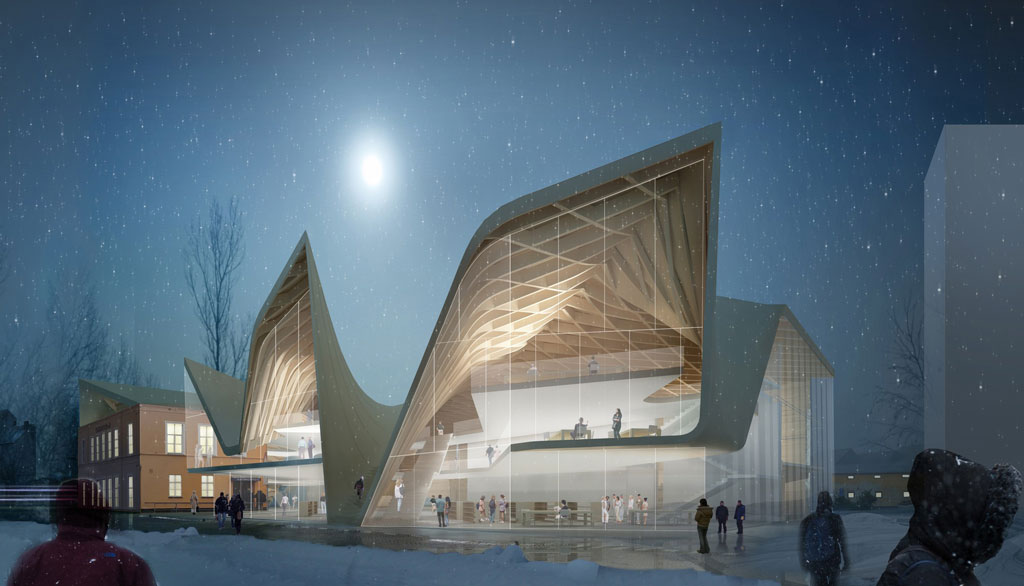

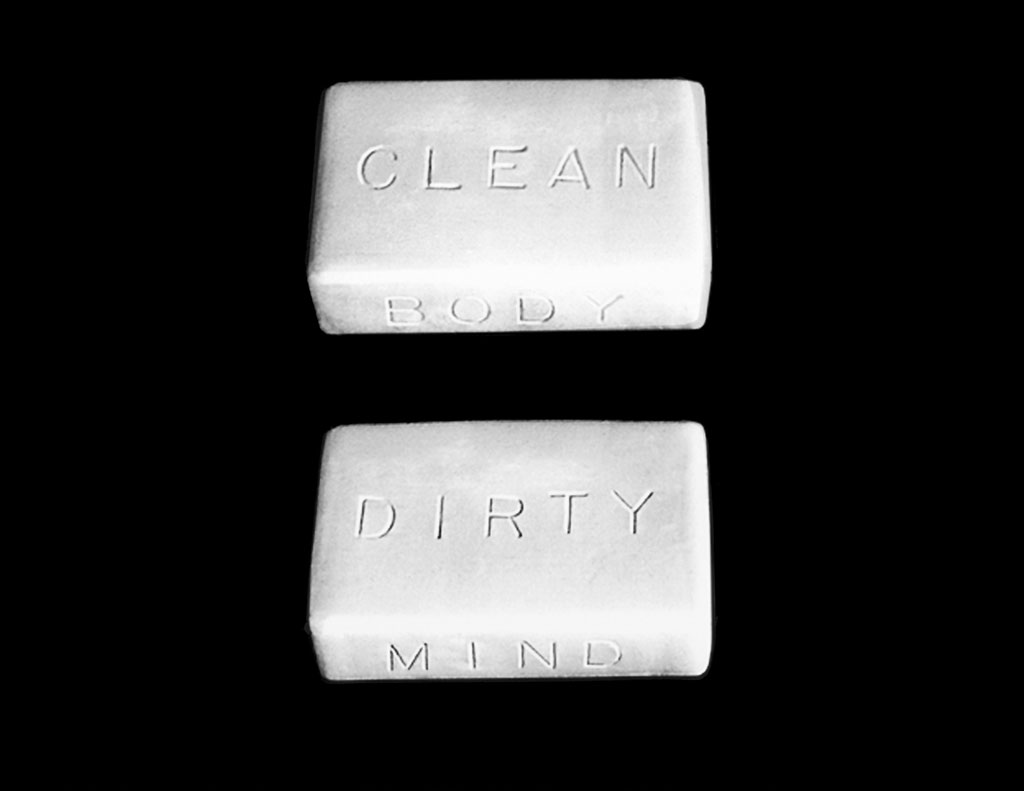

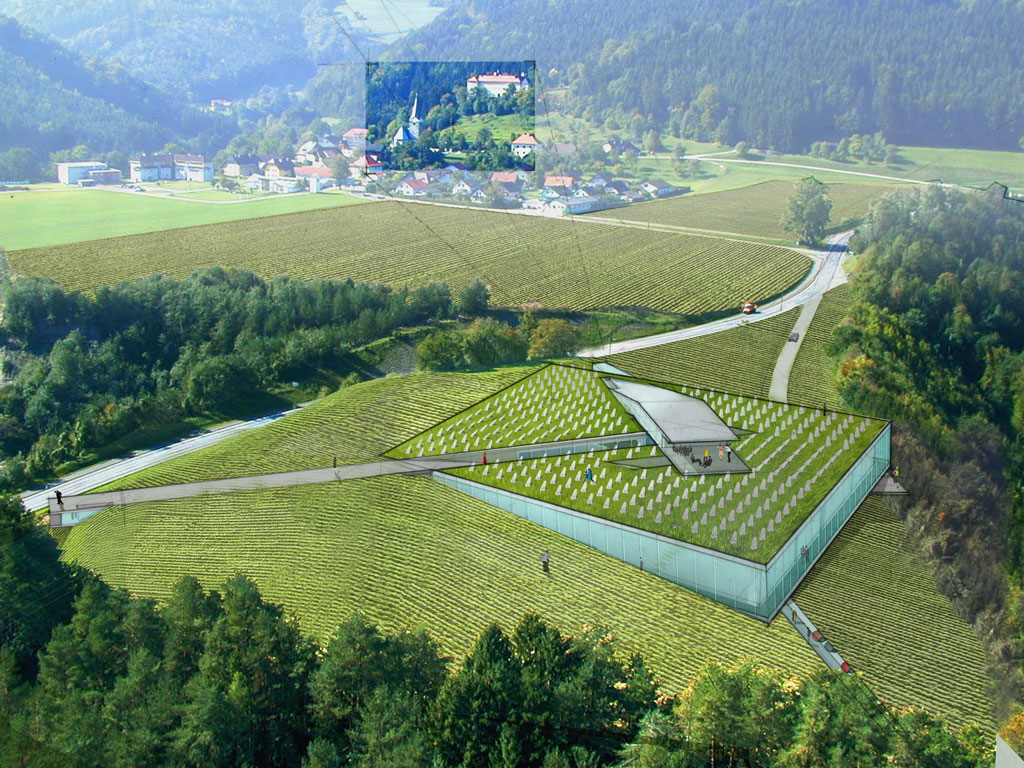

In the 1990s, Diller + Scofidio continued to explore the tension between architecture and art. While they were both considered highbrow artists, they were also highly reputable architects. This success led to such honors as a media residency at the Centre for New Media Research at the Banff Centre for the Arts from 1993–95. Throughout the decade, their works were commissioned for or shown at leading art institutions, and toured around the world. In 1991, Diller + Scofidio created “Tourism: SuitCase Studies”, which was originally displayed at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It consisted of 50 suitcases hung up, one for each of the United States. Each suitcase represented one state and was opened to reveal small items inside including tourist attractions and historical figures. Two years later, the pair created a controversial instillation located outside of New York City’s Rialto Theatre, a former pornographic theater. As part of the 42nd Street Project, Diller + Scofidio did “Soft Sell” on commission. The work featured a pair of big red lipsticked lips projected via video image on the exterior of the theater. The lips uttered phrases such as “Wanna buy a new lifestyle?” to passersby. Diller + Scofidio continued to push the barriers of their art into other mediums. In the mid–1990s, they published two books. The “Back to the Front” (1994) and “Flesh: Architectural Probes” (1995). In 1998, Diller + Scofidio moved into theater performance pieces with “Jet Lag”, consisted of two stories. One focused on the true story of a grandmother who wanted to obtain custody of her grandson from his father, and took him on 167 trans–Atlantic flights to keep him. The work focuses on their stops in airports. The other story was about a sailor who went alone on an around–the–world yacht race and filmed himself. His footage was projected as part of “Jet Lag”. While Diller + Scofidio explored other mediums, they continued to create installations for museums and galleries. In 1998, they did “The American Lawn: Surface of Everyday Lawn”, about the meaning of lawns in American life and how unnatural lawns can really be. More unusual was 1999’s piece, “Master/Slave”, originally displayed in France. The pair used a toy robot collection lined up on a 300–foot–long conveyor belt that moved along and passed through an airport security device. The robots were videotaped by security cameras, and the images appeared on monitors located in other parts of the gallery. Such works led to the MacArthur Foundation giving Diller + Scofidio a $375,000 grant in 1999 to continue their work. After the grant, Diller + Scofidio began designing more traditional architecture works, including buildings and interiors, albeit with their unconventional touch. In 2000, they renovated a restaurant in New York City called the Brassiere. Already a modernist place, they balanced their art with clients’ needs. They also created a low–income housing project in Gifu, Japan, which personalized the often limited space of public housing, and with others, a controversial viewing platform on Fulton Street in Lower Manhattan to give viewers a closer look at Ground Zero after the 11/9/2001, World Trade Center disaster. A more challenging and high profile project was the Blur Building created on Yverdon–les–Bains over Lake Neuchatel for the Swiss Expo in 2002. Diller + Scofidio worked for two years to create the unusual space. The Blur Building consisted of a steel structure that people could walk into and be inside a misty cloud as the structure was surrounded by fog–creating water nozzles. It was later the subject of a 2002 book by Diller + Scofidio entitled “Blur: the making of nothing”. At the time, the Blur Building was considered to be Diller + Scofidio’s defining work, but they soon received commissions to design larger projects such as the Institute for Contemporary Art in Boston, Massachusetts, and the Eyebeam Museum of Art and Technology in New York City, as well as smaller works such as a permanent installation in the John F. Kennedy International Airport and helping with the master plan for a cultural district around the Brooklyn Academy of Music. One of the design studio’s most noteworthy projects was the High Line in Manhattan, a former 1.45 mile-long elevated railway line adapted to create a linear park, constructed in several stages between 2009 and 2019. Once the initial plan to demolish the obsolete infrastructure was averted, DS+R design studio transformed the High Line into a beacon for residents, artists and nature lovers. The project has had a significant impact on the urban renewal process in New York, creating a lush green park and walkway that crosses blocks and old warehouses, often becoming a de facto public stage.