ART-TRIBUTE:Weaving and other Practices… Sheila Hicks

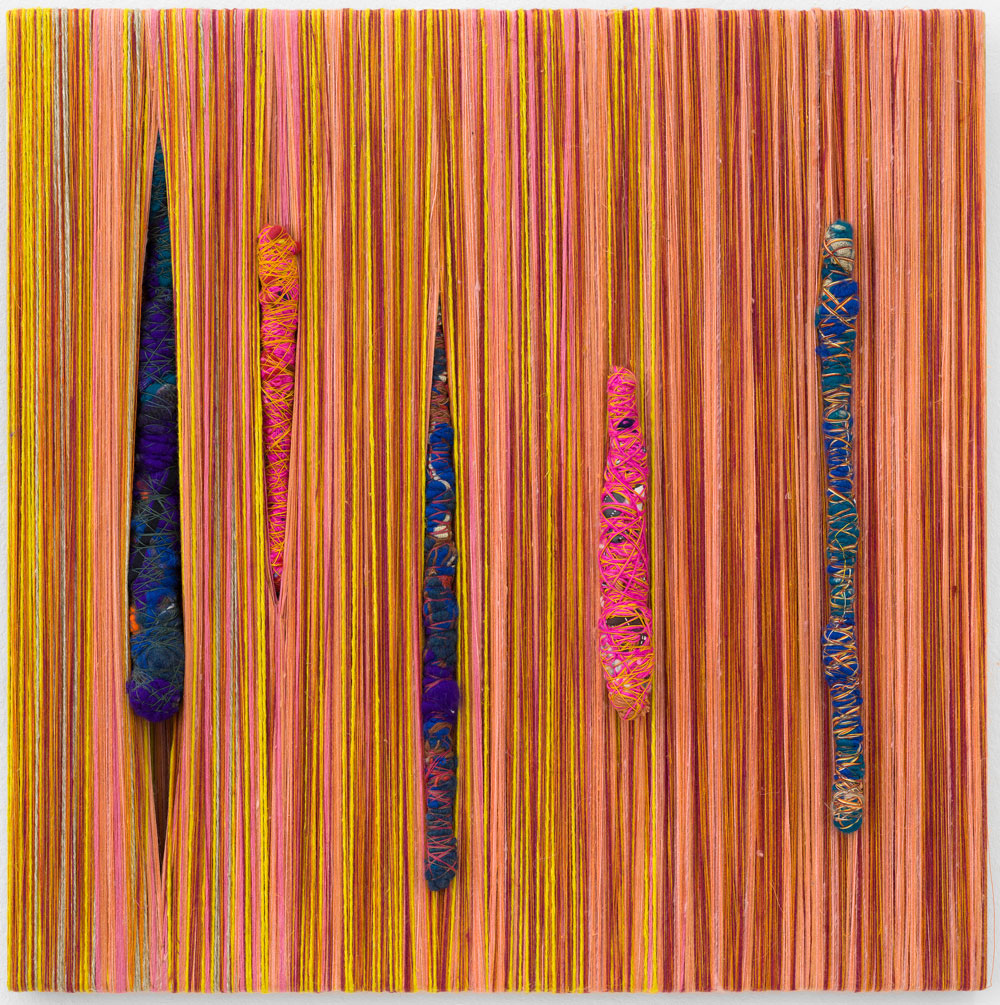

We continue our Tribute with Sheila Hicks (1934- ) a celebrated artist, known for her innovative use of weaving and textiles and her sculptural installations made of yarn. Her work ranges from small wall hangings, to enormous site-specific installations, and critics frequently locate her art at the intersection of decorative objects and fine art—though the artist herself in uninterested in the distinction.

We continue our Tribute with Sheila Hicks (1934- ) a celebrated artist, known for her innovative use of weaving and textiles and her sculptural installations made of yarn. Her work ranges from small wall hangings, to enormous site-specific installations, and critics frequently locate her art at the intersection of decorative objects and fine art—though the artist herself in uninterested in the distinction.

By Efi Michalarou

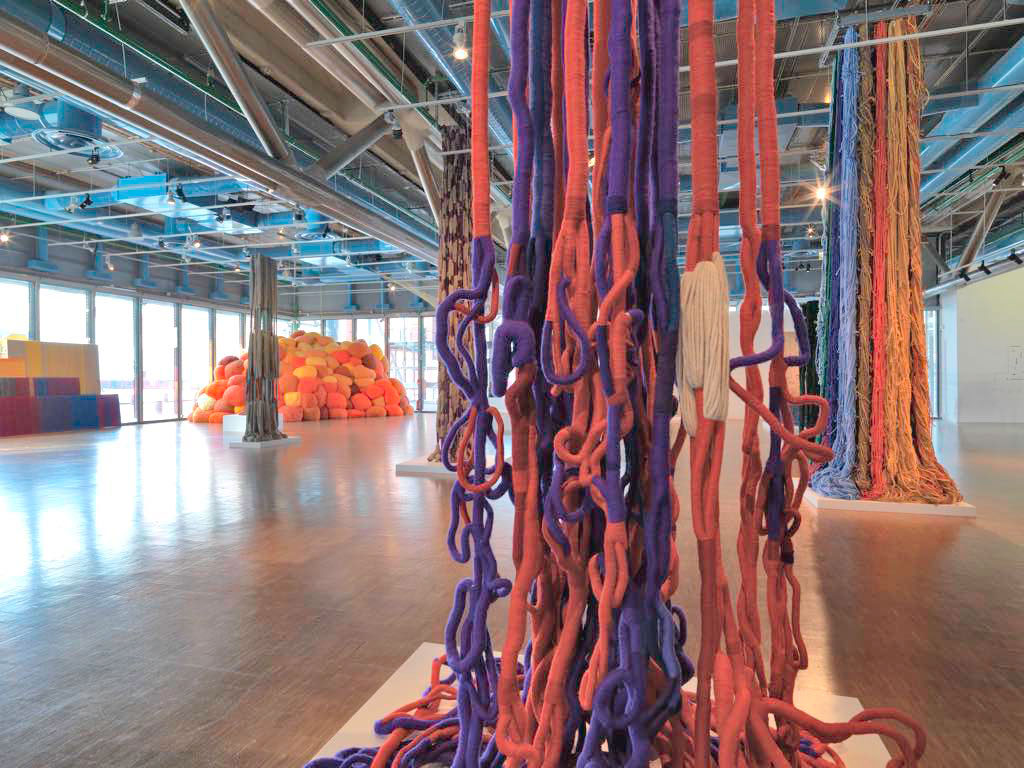

Sheila Hicks was born in the small town of Hastings, Nebada, in 1934,. Though her family moved around a lot during the Depression, Sheila Hicks and her brother returned each summer to Hastings, where their great-aunts instructed them in music, art and reading, as well as pioneer skills like spinning, sewing and weaving. She majored in art at Syracuse University, then transferred to the Yale School of Art where she studied with Josef Albersand with George Kubler, the influential historian of Latin American art. A picture of Peruvian mummy bundles, shown in Dr. Kubler’s class, sparked her interest in textiles, which was further galvanized when Albers took her home to meet his wife, Anni, the celebrated Bauhaus weaver. Hicks went to Chile on a Fulbright grant and traveled around Latin America, absorbing the influence of weavers in Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru. She received an M.F.A. from Yale, then returned to Mexico, where she photographed architecture and exhibited her “minims”. Some of her weavings entered the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. She also married a Mexican-German beekeeper, moved to his ranch and gave birth to a daughter, Itaka. Having lived briefly in Paris in 1959, and finding that her life and marriage in rural Mexico conflicted with her artistic aspirations, she returned here with her daughter in 1964, supporting herself as a textile design consultant for Knoll Associates and through work for a German carpet manufacturer. Her second husband, a Chilean artist introduced her to surrealist and Latin American circles in Paris, and through a curator at the MoMA she received her first big public commission, for a wall hanging at the restaurant of Eero Saarinen’s new CBS building in New York. A defining moment in her career came with her invitation to exhibit at the Biennial of Tapestry in Lausanne in 1967. In postwar Paris tapestry was promoted as a glory of French culture, but by the late ’60s the French organizers of this event were looking to shake things up. The monumental public commissions that have occupied her, intermittently, since the mid-’60s have often required complex studio setups and a phalanx of assistants: from her bas-relief medallion tapestries for the Ford Foundation headquarters in Manhattan (1966-67); to her wall hangings for a fleet of Air France 747s, stitched by hand in white silk (1969-77); to commissions for King Saud University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, (1982-85) and a cultural center in Fuji City, Japan (1992-93); to an immense linen-and-cork knot, some 20 feet high by 60 feet wide, for the corporate offices of Target in Minneapolis (2002-3). At the same time her temporary, poetic installations of found fabrics, a cascading mountain of some five tons of clean Swiss hospital laundry, for example, which was her contribution to the Lausanne Biennial in 1977, or the floating curtains of baby bands (used to bind a newborn’s umbilical wound), which she showed in a gallery in Kyoto in 1978 — explore the pervasive presence of cloth in every facet of human existence, from birth until death.

Sheila Hicks was born in the small town of Hastings, Nebada, in 1934,. Though her family moved around a lot during the Depression, Sheila Hicks and her brother returned each summer to Hastings, where their great-aunts instructed them in music, art and reading, as well as pioneer skills like spinning, sewing and weaving. She majored in art at Syracuse University, then transferred to the Yale School of Art where she studied with Josef Albersand with George Kubler, the influential historian of Latin American art. A picture of Peruvian mummy bundles, shown in Dr. Kubler’s class, sparked her interest in textiles, which was further galvanized when Albers took her home to meet his wife, Anni, the celebrated Bauhaus weaver. Hicks went to Chile on a Fulbright grant and traveled around Latin America, absorbing the influence of weavers in Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru. She received an M.F.A. from Yale, then returned to Mexico, where she photographed architecture and exhibited her “minims”. Some of her weavings entered the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. She also married a Mexican-German beekeeper, moved to his ranch and gave birth to a daughter, Itaka. Having lived briefly in Paris in 1959, and finding that her life and marriage in rural Mexico conflicted with her artistic aspirations, she returned here with her daughter in 1964, supporting herself as a textile design consultant for Knoll Associates and through work for a German carpet manufacturer. Her second husband, a Chilean artist introduced her to surrealist and Latin American circles in Paris, and through a curator at the MoMA she received her first big public commission, for a wall hanging at the restaurant of Eero Saarinen’s new CBS building in New York. A defining moment in her career came with her invitation to exhibit at the Biennial of Tapestry in Lausanne in 1967. In postwar Paris tapestry was promoted as a glory of French culture, but by the late ’60s the French organizers of this event were looking to shake things up. The monumental public commissions that have occupied her, intermittently, since the mid-’60s have often required complex studio setups and a phalanx of assistants: from her bas-relief medallion tapestries for the Ford Foundation headquarters in Manhattan (1966-67); to her wall hangings for a fleet of Air France 747s, stitched by hand in white silk (1969-77); to commissions for King Saud University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, (1982-85) and a cultural center in Fuji City, Japan (1992-93); to an immense linen-and-cork knot, some 20 feet high by 60 feet wide, for the corporate offices of Target in Minneapolis (2002-3). At the same time her temporary, poetic installations of found fabrics, a cascading mountain of some five tons of clean Swiss hospital laundry, for example, which was her contribution to the Lausanne Biennial in 1977, or the floating curtains of baby bands (used to bind a newborn’s umbilical wound), which she showed in a gallery in Kyoto in 1978 — explore the pervasive presence of cloth in every facet of human existence, from birth until death.![]()