ART-TRIBUTE:The Early Years of the Old Masters

In the turbulent 1960s of the Federal Republic of Germany, Georg Baselitz, Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke and Anselm Kiefer laid the foundation stone for their work, which is unique in German post-war art. Their works deal with a time when the worst of the war was cleared, but not the consequences of Nazi rule. Their works still inspire the viewer today to reflect on history, identity and how to deal with past and present. But what makes these works swing is, as always with good art, even more than that.

In the turbulent 1960s of the Federal Republic of Germany, Georg Baselitz, Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke and Anselm Kiefer laid the foundation stone for their work, which is unique in German post-war art. Their works deal with a time when the worst of the war was cleared, but not the consequences of Nazi rule. Their works still inspire the viewer today to reflect on history, identity and how to deal with past and present. But what makes these works swing is, as always with good art, even more than that.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Staatsgalerie Stuttgart Archive

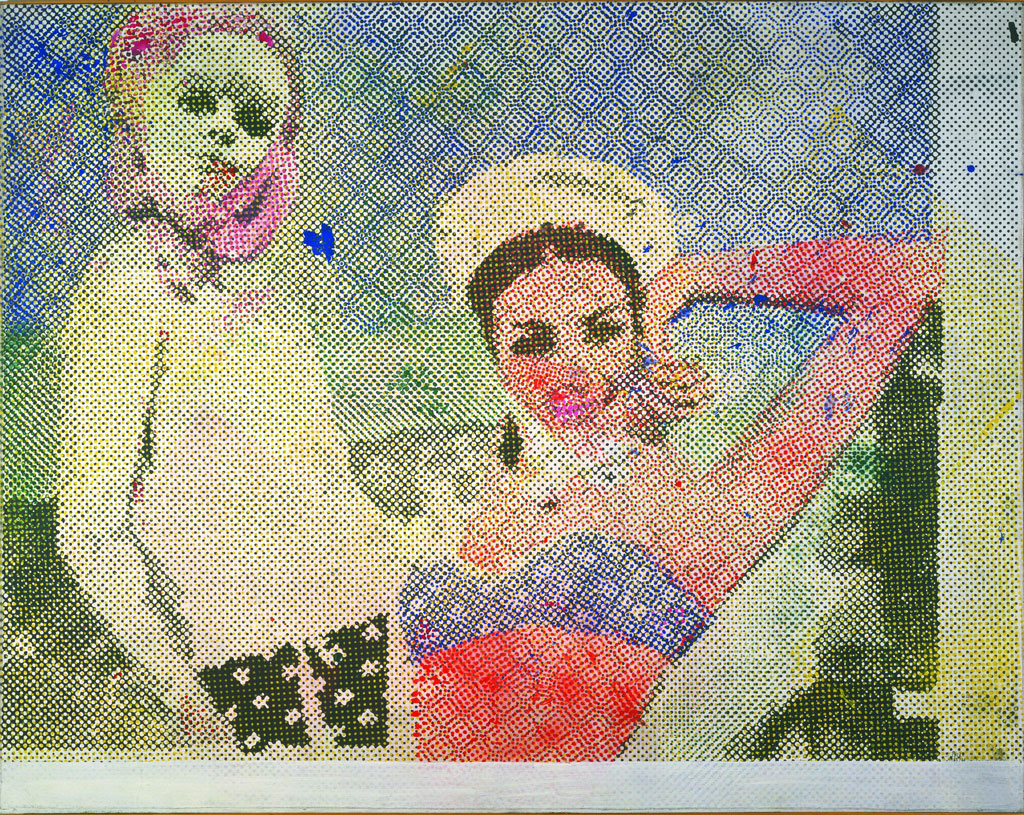

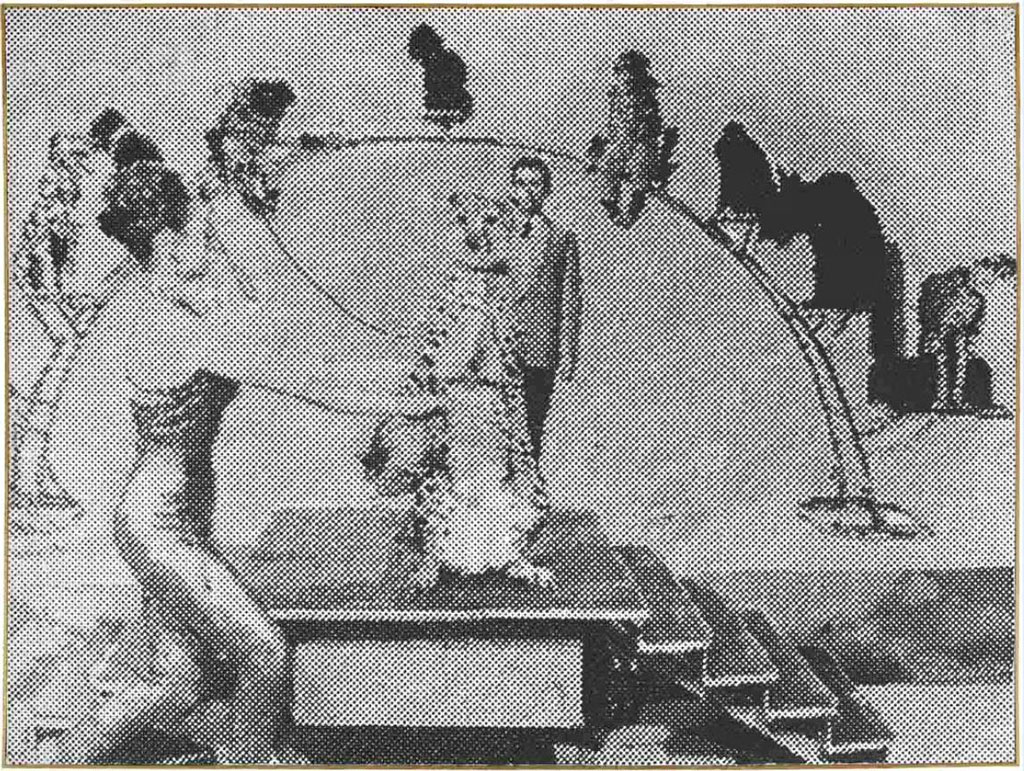

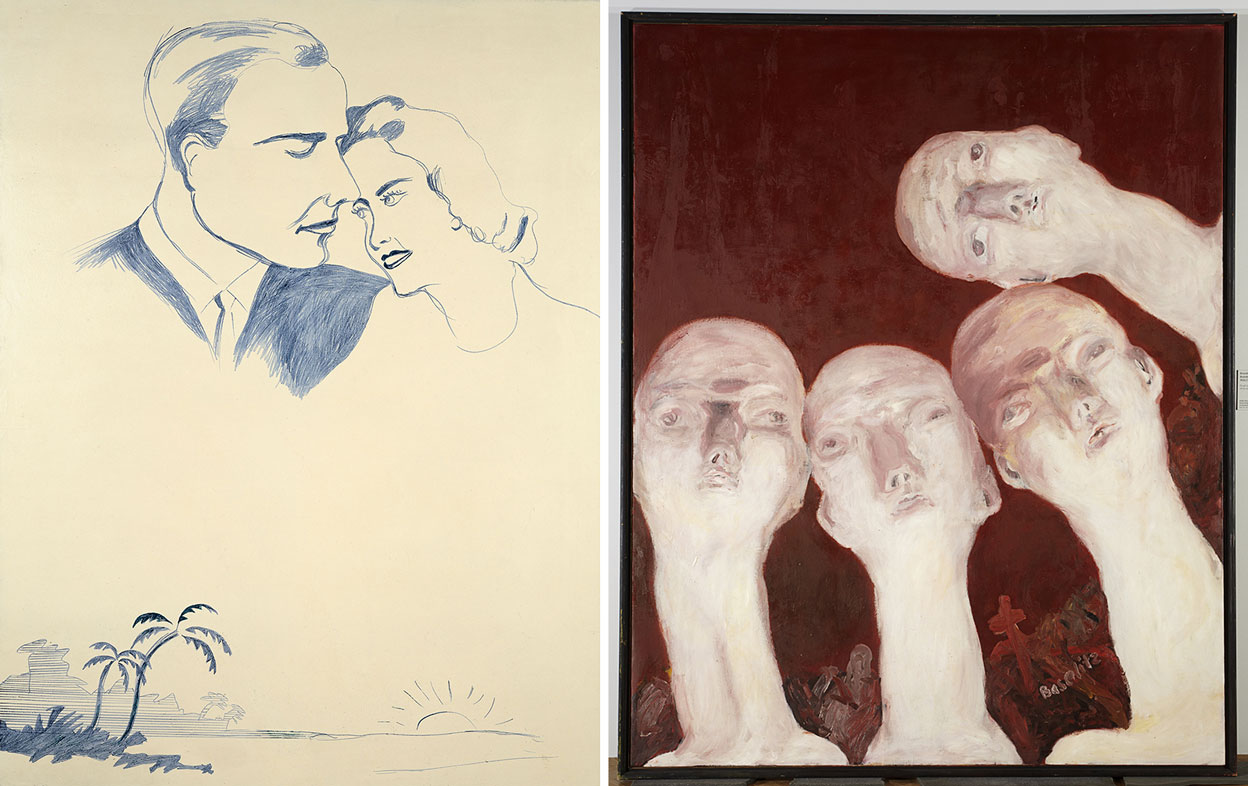

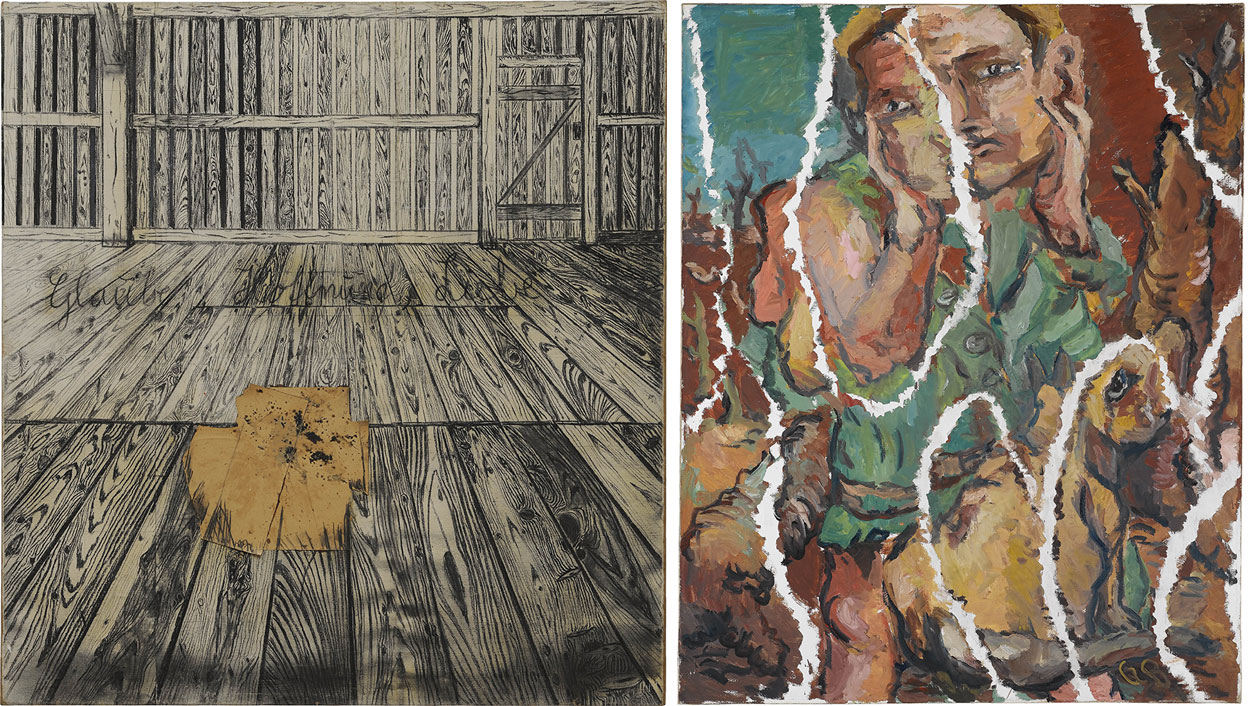

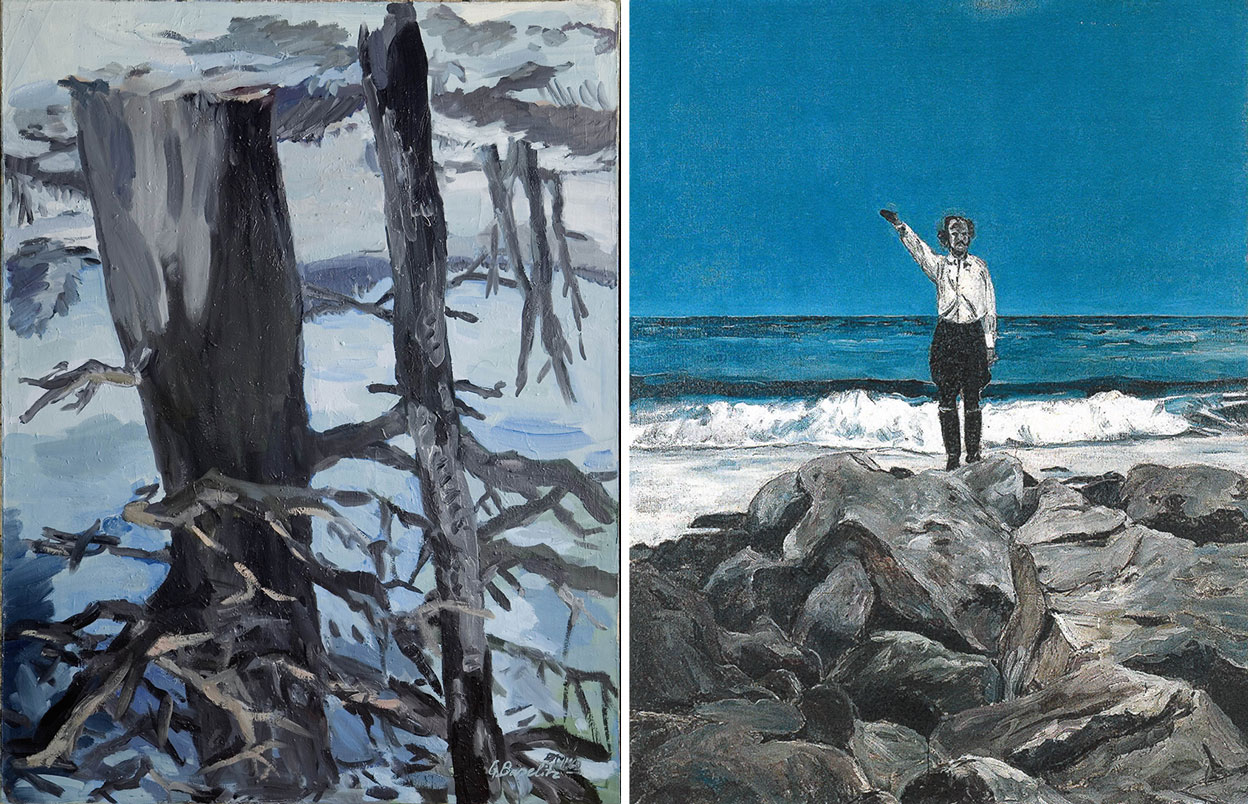

Featuring some 100 works the exhibition “The Early Years of the Old Masters: Baselitz, Richter, Polke and Kiefer” shows how, in the early years of their careers, these artists responded to an era characterized by challenges and upheavals, utopias and reorientations, power and protest. Except for Sigmar Polke, who passed away in 2010, each of the artists actively supported the exhibition project with the loan of outstanding works in their possession. The presentation, which highlights the artists’ intense engagement with their time and Germany’s recent history, will be complemented by a historical panorama of the concurrent political, social and cultural events – from the economic miracle of the 1950s and the resultant demands for a descent standard of living for everybody to the student revolts and the nascent extra-parliamentary opposition. Even if they all refer to themselves as apolitical, their art continues to shape the world’s positive image of a new, different Germany to this day. In the sixties, their figurative paintings challenged the primacy of abstraction. Georg Baselitz, painted heroes torn asunder. Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter unmasked the absurdity and emptiness of the consumption that beckoned from all sides. Anselm exposed the historical roots of the Third Reich. It is a stroke of luck to have the opportunity to unite works by the four masters in a single exhibition, and thus to shed light on this important phase in German history. “Der Wald auf dem Kopf” is Georg Baselitz’s first inverted painting, in which he upends his subject matter to frustrate recognition of the objects depicted. Its motif, based on a picture by the early-19th-century painter Louis Ferdinand von Rayski, is similar to those found in his previous work, but here he makes them secondary to the physical properties of the medium. This radical approach troubles our ability to interpret the picture, leaving us wondering whether we are now looking at an abstraction or, simply, a conventional landscape upturned. We might read it as symptomatic of Baselitz’s continuing attempts to find a different path from those that had been dominant when he emerged – the gestural abstraction of Paris and New York, and the Socialist Realism of the Eastern bloc. Gerhard Richter’s paintings have been referred to as models of perception. Indeed, his work is as much about the act of looking as any other subject. In his photo-based works, Richter combines various tropes of painting and photography to create a kind of representational problem: how and when does the eye sense the difference between a painted surface and the photographically recorded? In Richter’s seemingly conventional yet large-scale “Seestück (bewölkt)”, the pigment is thinly applied, resulting in a surface that emulates the flatness of a photograph. And, like a snapshot might be, it is blurred. Here, the visual becomes conceptual, as Richter literally obscures the distinction between the photographic and the painted. Seascape, which also recalls the moody, atmospheric landscapes of German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, is the first work by Richter to enter Bilbao’s collection. In 1963 Sigmar Polke organised an exhibition with fellow students Gerhard Richter and Konrad Lueg (later Konrad Fischer) called “Capitalist Realism”. The exhibition was mockingly titled after the realist style of art known as “Socialist Realism”, then the official art doctrine of the Soviet Union, but it also commented upon the consumer-driven art ‘doctrine’ of western capitalism. Polke’s early work has often been characterised as European Pop art for its depiction of everyday subject matter – combined with images from the mass media. But in contrast to the slick and polished style of American Pop, Polke’s early drawings have a childlike clumsiness which implies an ironic attitude both to the culture of commodity worship and the issue of ‘appropriate’ subject matter for art. Parallels with mainstream Pop art are also visible in Polke’s paintings which imitate the dotted effect of commercial printing techniques. In Girlfriends (1965), Polke challenges the authority of the printed image by exaggerating the mishaps and unreliability of the mechanical process: colours are ‘off-register’ and the dots blur together into abstract, meaningless patterns. During this period Polke also began to use commercially-produced fabrics instead of canvas, incorporating the printed patterns into the composition of the painting. By combining these different styles and techniques, Polke unpicks and exposes the codes and structures of image-making, asking the viewer to question traditional methods of evaluating art. For his notorious body of work “Heroisches Sinnbild”, Anselm Kiefer created a series of photographic self-portraits that confronted, head on, the history of Nazi Germany. Dressing in his father’s military uniform and posing in the Hitlergruss salute, Kiefer had his photograph taken in various politically significant locations in Switzerland, France, and Italy, including national monuments and classical ruins. By posing in a traditionally Romantic stance and extending his arm in the Nazi salute, Kiefer connects these two seemingly disparate periods of German history to suggest that Germany’s love of country has been an enduring part of their history at least since the early-19th century. The imperialist and nationalistic attitudes of the Romantic era, instigated by Napoleonic invasions, were manipulated by the leaders of the Third Reich, leading to the tragedies of the Holocaust. While this work is stylistically very different from his later work, this series introduced themes that would become central to Kiefer’s explorations of Germany’s legacy and national trauma.

Info: Curator: Götz Adriani, Assistant Curator: Cäcilia Henrichs, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Konrad-Adenauer-Straße 30-32, Stuttgart, Duration: 12/4-11/8/19, Days & Hours: Tue-Wed & Fri-Sun 10:00-17:00, Thu 10:00-20:00, www.staatsgalerie.de

![Left: Gerhard Richter, Schwimmerinnen, 1965, oil on canvas, 200 x 160 cm, Sammlung Froehlich, Stuttgart, © Gerhard Richter 2018. Center: Gerhard Richter, Kuh II [Cow II], 1965, oil on canvas, 157 x 113 cm, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, transfer from the Baden-Wuttembergisches Kultusministerium 1968, © Gerhard Richter 2018. Right: Gerhard Richter, Schloss Neuschwanstein, 1963, oil and enamel on canvas, 190 x 150 cmMuseum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, © Gerhard Richter 2018](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/0511.jpg)