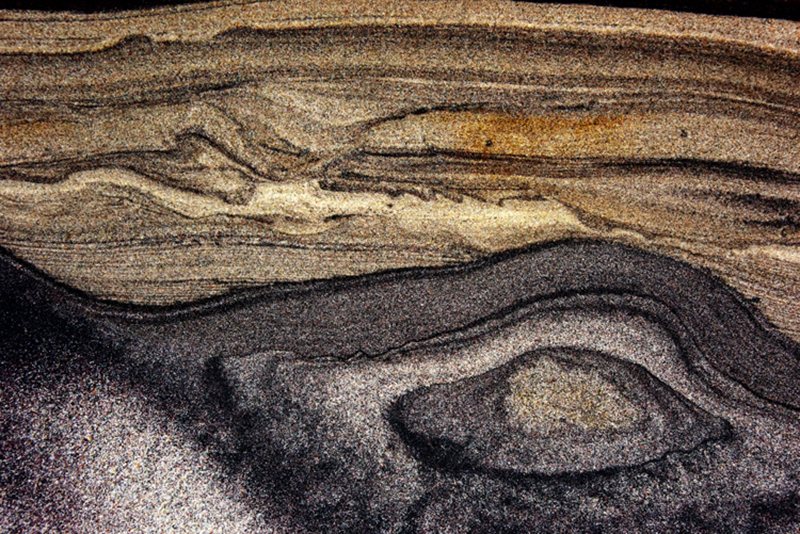

NEW COMERS: Xiomáro

The American photographer Xiomáro break in photography in 2010 when he was selected as an artist-in-residence at the homestead of impressionist painter Julian Alden Weir, now the Weir Farm National Historic Site in Wilton at Connecticut. He graduated from New York University School of Law, and became an arts-and-entertainment lawyer and manager representing creative talents. After he recovered from a serious health issue he turned to art, particularly to photography. He focused on Landscape Photography that has a long tradition in U.S.A., but ever he was passionaded with music. Xio has completed several commissions for the National Park Service including Theodore Roosevelt’s Sagamore Hill mansion in Oyster Bay and the High Dune Wilderness on Fire Island. On the occasion of the 100 year anniversary of the National Park Service, we focus on his photographs on exhibition at the Patchogue Ferry Terminal. We are discussing with him about the relationship of his work with the Land Art and the Nature, the challenge to exhibit at a ferry station and shares with us his big personal project (dream of his life), to shooting with his lens, the opposite direction that followed Ansel Adams…

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Xiomáro Archive

Mr. Xiomáro, we know you started your career as a lawyer but a serious health issue made you turn into art and specifically in landscape photography, which has a long tradition in the USA. How did you make this decision and what does photography mean for you?

I was an entertainment lawyer representing Village People, Lisa Lisa, The Jerky Boys and many Gangsta rap artists. I also wrote, recorded and performed my own music with a back-up band. One of my songs even made it to the Top 40 of American Idol Underground. I used to document my concerts with a small point-and-shoot camera. Eventually I took snapshots of decorative scenery and those prints would often outsell my CDs. But it was difficult to keep a band together that was serious about achieving success. Just as we were reaching a peak, I was diagnosed with cancer. It was caught early enough for me to recover and the experience moved me to streamline my life by doing away with relationships that were impeding me artistically. The peace in photographing the landscape, especially in the National Parks, helped my emotional recovery. Since my snapshots had been selling well, I bought the best camera I could afford at the time and decided to pursue photography as a serious artistic pursuit instead of music. As a photographer working alone, I could work as hard as I desired to get better at my art without a band to hold me back.

In 2010, you were selected as artist-in-residence at the Weir Farm National Historic Site (home of Impressionist painter Julian Alden Weir) in Wilton, Connecticut. Does this mark a breakthrough in your career, since it was followed by a series of commissions from the National Park Service?

It was definitely a breakthrough. After cancer, I photographed in obscurity for about 5 years. I was learning, experimenting and creating small thematic collections. But I was not sure how to take the next step in getting paid commissions, getting my photographs exhibited and developing some acclaim in the art world. Being selected as Weir Farm’s artist-in-residence in 2010 gave me the time to create a more serious body of work, as well as my first exhibit and media interview. Weir Farm was pleased with my work and presented me with my first paid commission. Within a few months and a lot of very hard work, I had two major exhibits and a lot of media coverage. That success and exposure led to more commissions with the National Park Service that continues to this day.

At a time when our planet is terribly worn out, do you think that through your projects, you can accomplish a positive role in raising public awareness through the respect and admiration of the beauty of the landscape and ultimately the rescue of the ecosystem?

I have long had a mission-oriented approach to art projects. For me, it is not fulfilling to simply complete a project and then move on to the next one. The money and the credentials are not enough. I am always thinking about how to get my art exposed to the largest audience possible and to engage that audience through gallery talks, books, articles and interviews on television, radio, print publications and the internet. When I hear a great rock band, I feel motivated: to play an instrument, to talk about the song with others, to adopt the point of view of the song lyrics. It takes me someplace new and the effect is long lasting. If I can have that kind of effect on other people with my photographs, then I feel I have really achieved something. I would like for my images to not only stand on their own as art, but to move someone to action: to support environmental causes and political candidates, to try living a “greener” lifestyle, to take a break from the virtual world of one’s electronic device and enjoy the natural world. I have worked with a Senator, Congressman and Mayor to exhibit my work in public spaces with high visibility. So, hopefully, I have made a small contribution to raising awareness about rescuing the ecosystem.

You have exhibited in many different spaces. How challenging and interesting is the Patchogue Ferry Terminal gallery space on the occasion of the centennial of National Park Service?

My longest show was a one-year solo exhibit at Harvard University and my highest-profile exhibit was called The Other Side, which focused on the slaves of William Floyd, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. Unlike these exhibits, the Patchogue Ferry Terminal presents a challenge in that I am part of a group exhibit and the gallery space is only open on weekends for the summer. So the engagement is limited. On the other hand, the exhibit is significant in that it celebrates the 100 year anniversary of the National Park Service and the gallery is at the terminal, which is another public space having a built-in audience. A steady stream of visitors is guaranteed as these travelers need to arrive and depart according to the ferry schedule. So now they get to enjoy the exhibit while they wait for their boat or as they disembark.

Although technology has taken off and you could use all its technical advantages, you prefer the natural day light. What role does it play in your work and what are the advantages and the disadvantages?

I have seen some beautiful work done with flashes and other electronic lighting. I have used this equipment in my own work too. But, for me, I always find natural lighting to look the best. There are many advantages: it’s flattering and natural looking, it’s free of charge and is as “green” as you can get! The disadvantages are that, unlike artificial lighting, it cannot be controlled and it is unpredictable. The lighting is different depending on the weather, the season, the time of day and where you are located in relation to the sun. On the other hand, learning how to photograph under those circumstances helps to keep the work challenging and fresh. You can achieve some interesting results with lots of variety. I love the drama and mystery that can be evoked with the use of natural light and shadow.

In your work you are in direct contact with nature like the Landscape Artists. How close do you think is your work to Landscape Art and how has it affected you?

I think my work is close to that of the landscape artists in the sense that we are trying to bring images of nature to an increasingly urbanized society. Albert Bierstadt, for example, painted extremely large canvasses having dramatic light and shadow, saturated colors and small, almost imperceptible, animals or people to convey the grandeur of the American West. Powerful images like this had a part in the move to establish the world’s first national parks. Although my aesthetic is not influenced by Bierstadt or other landscape painters like Thomas Cole, Frederic Church or Thomas Moran, I am inspired by how their work helped create awareness for the appreciation, conservation and preservation of nature.

You stated that, like Ansel Adams who covered with his lens the West, you want to cover the East. What are the difficulties of the East? What are the challenges? Is this a life project that has been started? What differences or specific features does one encounter in the landscape?

Yellowstone became the world’s first national park. Other national parks in the West include the Grand Canyon, Yosemite and the Redwood Forest. So it’s hard to think of the East in comparison to these landscapes. But there are many National Park historic sites that are uniquely eastern. For the past 6 years, I have been creating a larger body of work that I call America’s Cradle: New England in Photographs. The New England region, located in the Northeast, is where the nation began. So far I have been commissioned to create artistic photographic collections of the homes and grounds once belonging to political and cultural leaders such as William Floyd (a signer of the Declaration of Independence), Theodore Roosevelt (President of the United States), Julian Alden Weir (the father of American Impressionist painting), Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (a world renown poet) and Frederick Law Olmsted (who established the world’s first office for landscape design). Many of my photographs present viewers with rare views: close-up images of historical artifacts that are not on display and areas of these sites that are not generally accessible to the public. I like to think of these eastern sites as cerebral landscapes. Visitors can see where the nation’s early thinkers worked and lived. In addition to these historic sites, I have also photographed four eastern park units with unique landscapes and histories: Boston Harbor National Recreation Area, which encompasses 34 islands; Fire Island National Seashore, one of 10 federally protected seashores in the country; and Florida’s Big Cypress National Preserve and Everglades National Park. The vistas, wildlife, plants and terrain in these parks is like nothing one will experience in the West. As this represents only a small portion of the National Parks of the East, it is more than likely that America’s Cradle will continue as a life-long project.

First Publication: www.dreamideamachine.com

© Interview-Dimitris Lempesis

Info: Fire Island National Seashore Patchogue/Watch Hill Ferry Terminal, Patchogue, NY, Duration: 31/7-4/9/16, www.nps.gov