ART CITIES: London-Richard Hunt

Richard Hunt’s sculptures often used salvaged materials like scrap metal and car parts. Hunt’s creations were deeply personal and richly symbolic, influenced by the natural world, myths from Greek and Roman history, his cultural background, global travels, the principles of European modernism, and the impact of the Civil Rights Movement. Through constant experimentation with scale, materials, composition, and themes, Hunt developed a significant body of work that continues to influence American sculpture today.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: White Cube Gallery Archive

“Metamorphosis – A Retrospective” marks the first posthumous retrospective and the first major European exhibition dedicated to Richard Hunt, whose innovative and intuitive command of metal forged a singular presence within the canon of 20th- and 21st-century sculpture. Spanning more than six decades, the exhibition traces the evolution of Hunt’s prolific career through over 30 major works, created between 1955 and his passing in 2023. A core aspect of his approach was a commitment to freedom, advocating for personal liberation and expanding the limits of political and artistic expression. His innovative techniques and unique combination of mechanical and organic elements transformed the landscape of metal sculpture, creating new styles that altered American modernist art. Emerging from a rich tapestry of cultural influences, his journey showcases both his artistic growth and the racial obstacles he faced, highlighting a narrative of innovation, accomplishment, and a legacy that continues to inspire artists. Richard Hunt was born in Chicago on 12/11/1935. A descendant of slaves brought to the U.S. through the port of Savannah, Georgia, Hunt grew up on the South Side of Chicago, first in Woodlawn and then Englewood. His father was a barber and his mother was a librarian. During his youth, he was immersed in Chicago’s cultural and artistic heritage through art lessons at the South Side Community Art Center (SSCAC) and the Junior School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Regular visits to Chicago’s major public museums trained his eye and captured his interest in African art. Hunt would go on to develop an extensive collection of African Art, with more than 1,000 artifacts, which inspired his work. In the spring of 1953, he encountered the work of Spanish sculptor Julio González at the Art Institute of Chicago. González’s forged, hammered and welded metal sculptures became one of the formative influences on the young artist. Hunt enrolled at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) in the fall of 1953, after receiving a prestigious scholarship from the Chicago Public School Art Society. Inspired in part by González, Hunt decided to solely become a metal sculptor, teaching himself to solder, and later weld, the discarded metal that he scavenged from local scrapyards in Chicago. By 1955, Hunt would sell his soldered wire sculptures, along with paintings and drawings, at local art fairs and galleries, marking the formal beginning of his career as an artist. When Hunt was 19 years old, in September of 1955, he witnessed the open-casket funeral of Emmett Till in Chicago. Till, who was abducted, tortured, and lynched in Mississippi, had grown up only two blocks from the Woodlawn home where Hunt was born. Hunt went on to create art shaped by this experience, which influenced his artistic expression and commitment to the Civil Rights Movement. In the immediate aftermath, he made two works: “Prometheus” (1956), where Till’s suffering is linked to the myth of the god of fire, and “Hero’s Head” (1956), which immortalized the image of Till’s disfigured head in welded steel. Throughout his life and work, the Civil Rights Movement remained a driving force, shaping Hunt’s artistic process as he commemorated those individuals central to the cause. In the spring of 1957, at just 21 years of age and a senior at the SAIC, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) acquired Hunt’s welded steel sculpture, “Arachne” (1956), earning him national recognition. Arachne–which Hunt based on the Greek myth of Arachne, a skilled weaver transformed into a spider by the enraged goddess of weaving, Athena–was included in MoMA’s 1957 exhibition, “Recent American Acquisitions”. MoMA’s acquisition of this welded steel figure catapulted Hunt to the forefront of modern contemporary sculpture.

Upon graduating from the SAIC in 1957, Hunt won the James Nelson Raymond Fellowship for “Untitled” (1957). The sculpture was inspired by Pablo Picasso’s iron sculpture “Woman in the Garden” (1929–30), a collaboration with the Spanish sculptor Julio González, which served as an homage to the French Surrealist poet Guillaume Apollinaire. The fellowship enabled Hunt to travel to Europe, specifically England, France, Spain and Italy to study art for one year. He worked at the famous Fonderia Artistica Ferdinando Marinelli in Florence, where he learned to cast and created his first bronze sculptures. He also visited Constantin Brâncuși’s studio in Paris, a combined living and working space that would later inspire his decision to live and work in his own studio at West Lill Avenue in Chicago. Hunt returned to the U.S. in 1958, when he was called to serve in the U.S. Army at Brooke Army Medical Center in Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio, Texas. Incredibly, during that same year, Hunt held his first solo exhibition in New York at the Alan Gallery. However, due to his military service, he could not attend the opening reception. On 16/31960, while still serving in the army in San Antonio, Hunt was the first African American to be served at the segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter in Alamo Plaza. This determined act of conscience made San Antonio the first peaceful and voluntary lunch counter integration in the South. Hunt would return to Chicago in the summer of 1960, and by 1962 establish his first formal studio space on North Cleveland Avenue. Inspired by the unveiling of the colossal “Chicago Picasso” in 1967, Hunt began creating works of Cor-Ten steel and later bronze and stainless steel, which he continued using throughout his career. Hunt also produced works of cast metal, usually aluminum or bronze, and was an accomplished draftsman who created drawings, lithographs, and screenprints, in addition to many sketched works. In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Hunt to a six-year term on the National Council on the Arts, filling the seat left vacant by the untimely death of the sculptor David Smith. Hunt was the first African American visual artist to serve on the council. In 1971, at only 35 years of age, Hunt achieved a historic milestone by becoming the first African American sculptor to have a retrospective at MoMA. The exhibition, “The Sculpture of Richard Hunt”, featured 55 sculptures, eight drawings and 12 prints. Hunt’s exhibition and the simultaneous “Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritua”l, devoted to the Harlem Renaissance painter Romare Bearden (1911–1988), are the museum’s first solo shows by African American artists. Also in 1971, Hunt purchased a former Chicago Railway Systems Company electrical substation, built in 1909, at 1017 West Lill Avenue, in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood. The structure had natural light from cathedral-like windows as well as an overhead bridge crane ideally suited for moving large sculptures, which allowed him to significantly increase the scale of his welded works. The new studio space enabled Hunt to pursue larger public commissions. Hunt sculpted major monuments and sculptures for some of our country’s greatest heroes, including Martin Luther King, Jr., Mary McLeod Bethune, Jesse Owens, Hobart Taylor, Jr., and Ida B. Wells-Barnett. His sculptures commemorate events from the slave trade and the Middle Passage to the Great Migration. His massive 1,500-pound bronze, “Swing Low” (2016), a monument to the African American Spiritual, hangs from the ceiling of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. Hunt’s masterpiece, “Hero Construction” (1958), stands as the centerpiece of the grand staircase at the Art Institute of Chicago. Hunt considered artistic freedom to be the most important aspect of his career: “I am interested more than anything else in being a free person. To me, that means that I can make what I want to make, regardless of what anyone else thinks I should make.” That artistic freedom has been recognized and celebrated by multiple institutions from which he received 17 honorary degrees and held more than twenty professorships and artist residencies at institutions such as Harvard, Yale, Cornell, Northwestern, the School of the Art Institute, and the University of Illinois.

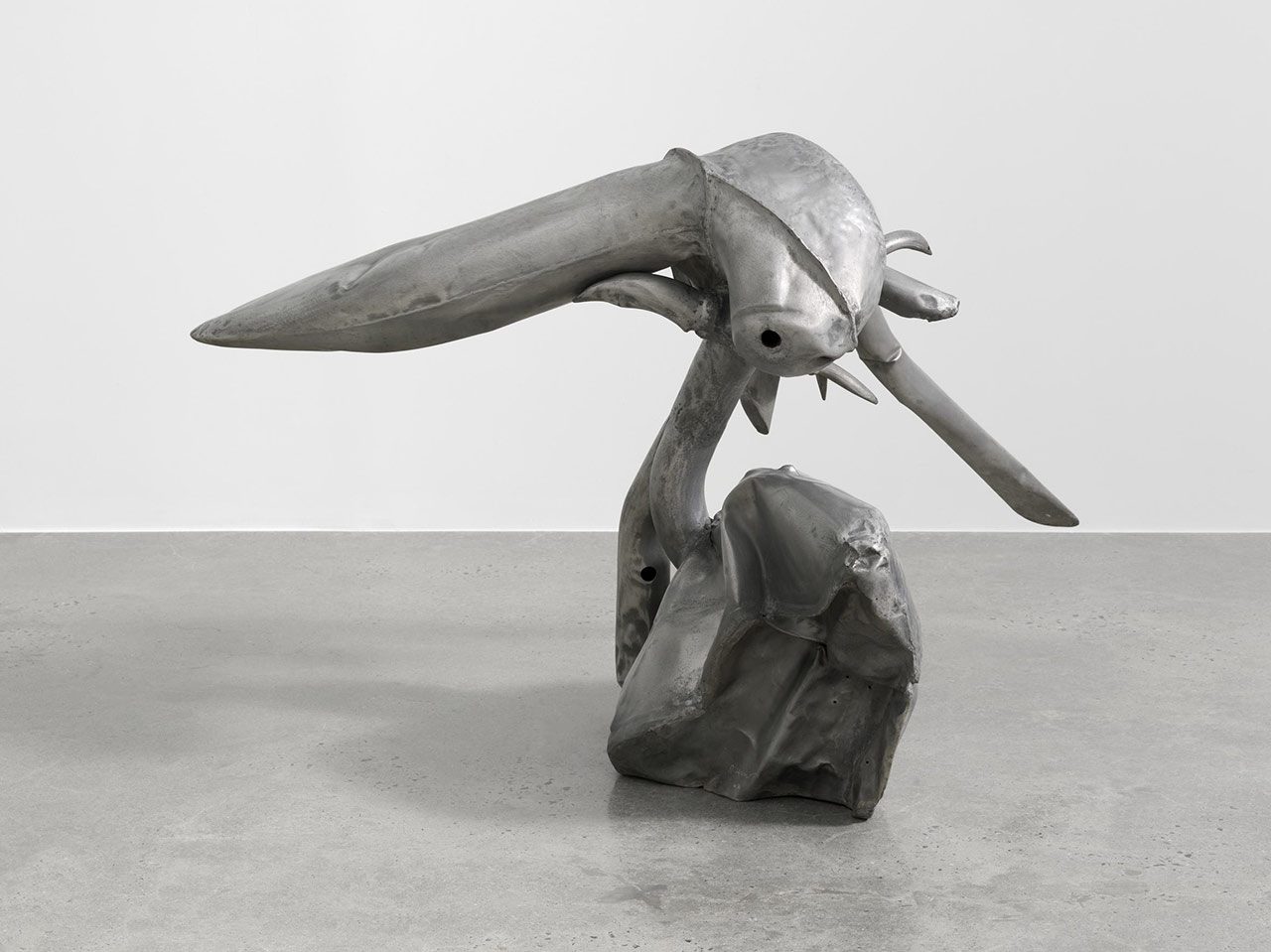

Photo: Richard Hunt, Tube Form, 1966, Welded aluminium, 87.6 x 134.6 x 88.3 cm | 34 1/2 x 53 x 34 3/4 in., © Richard Hunt Legacy Foundation, Courtesy Richard Hunt Legacy Foundation and White Cube Gallery

Info: White Cube, 144 – 152 Bermondsey Street, London, United Kingdom, Duration: 25/4-29/6/2025, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, Sun 12:00-18:00, www.whitecube.com/

![Richard Hunt, Hero's Head] 1956, Welded steel and stainless steel base, 30 x 29 x 29 cm | 11 13/16 x 11 7/16 x 11 7/16 in., © Richard Hunt Legacy Foundation, Courtesy Richard Hunt Legacy Foundation and White Cube Gallery](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/a217353.jpg)

Right: Richard Hunt, Construction S, 1956, Welded steel and catalpa wood, 148 x 75 x 92 cm | 58 1/4 x 29 1/2 x 36 1/4 in., © Richard Hunt Legacy Foundation, Courtesy Richard Hunt Legacy Foundation and White Cube Gallery