TRIBUTE: Ed Atkins, Part II

One of the most influential British artists working today, Ed Atkins is best known for his computer-generated videos and animations. Repurposing contemporary technologies in unexpected ways, his work traces the dwindling gap between the digital world and human feeling. He borrows techniques from cinema, video games, literature, music and theatre to examine the relationship between reality, realism and fiction (Part I).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Tate Archive

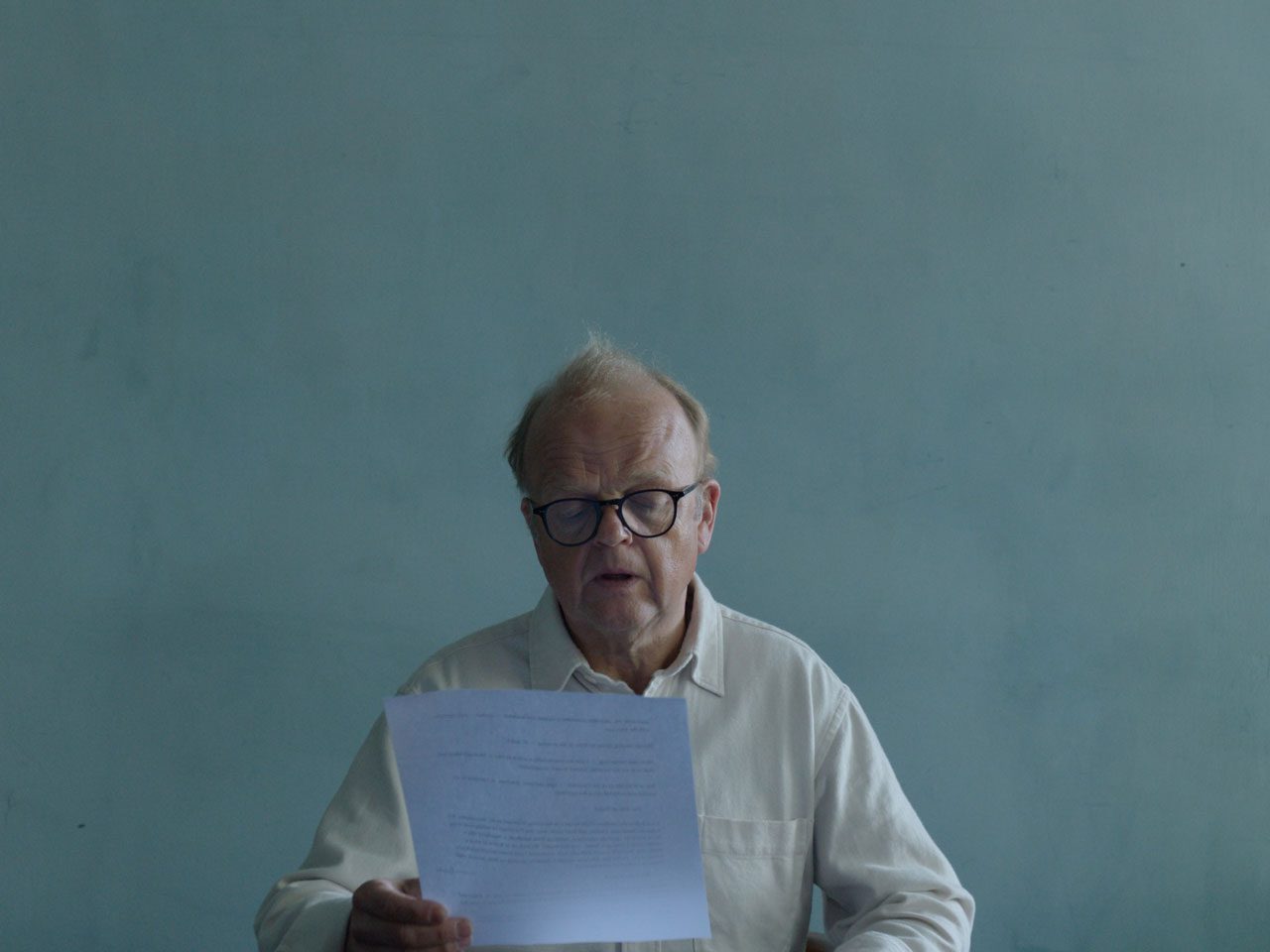

Ed Atkins largest UK survey exhibition to date features moving image works from the last 15 years alongside writing, paintings, embroideries and drawings. In these works, the artist uses his own experiences, feelings and body as models to mediate between technology and themes of intimacy, love and loss. Together, they pit a weightless digital life against the physical world of heft, craft and touch. Repetition and difference act as a structural device throughout the show. Atkins split artworks across rooms, repeat them or alter their format. He wants to induce a sense of the familiar made strange, of digression, mistake, confusion, incoherence and interruption. For him, this exhibition represents a reimagining of the messy reality of life: the more we experience, the more complex and less contained it becomes. The exhibition begins with two early video works: “Death Mask II: and :Cur” (both 2010), described by Atkins as “montages of intoxication, rejection and abandonment”, these early videos announce the artist’s distinctive visual and auditory syntax, and a mood and address that can be found throughout all of his videos. These early works also introduce Atkins’ foregrounding of medium and the technologies used in their making. Whether through conspicuous lens flares or autofocus racking or seemingly involuntary blurts of audio, the artist wants us to remember that we are looking at something profoundly artificial, built to seduce and repulse. Later works see Atkins shift into almost exclusively using computer-generated animation. “Refuse.exe” (2019), uses a video game engine to tip a stream of trash onto a stage, and ‘Hisser” (2015), shows a male figure, animated by Atkins’ performance, who apologises, masturbates, and falls into a sinkhole. Many of the videos are also performances of the artist, as recorded using performance capture technologies. “The Worm: (2021), for example, features an animated TV staging of a phone call between Atkins and his mother, while “Pianowork 2” (2024_ has an extremely accurate digital double of the artist performing a minimalist piano piece. Self-portraiture is another consistent thread in Atkins’ work; it is always a version of Atkins stalking his works, and more often than not, his figures – surrogates – are entirely alone. The exhibition includes realistic pencil drawings of the artist’s face and limbs as well as convincing paintings of mattresses and pillows bearing traces of absent bodies. Atkins’ neurotic examination of his own body speaks to the ever-expanding anxiety of contemporary self-identity, but also to an ancient sense of a person striving to understand something of who they are, and who they appear to be. Whether in analogue or digital form, Atkins’ works are an entanglement of reality, artifice and the psychopathology of everyday life. At the heart of the exhibition is a mass of drawings on Post-It notes which the artist makes for his children. Atkins describes them as “miniature images of seemingly infinite invention” and “tiny, laboured, inscrutable attempts to communicate feeling.” For him, these Post-It note drawings are something like a legend at the bottom of the map, teaching us a way of looking and of feeling. The drawings are also joyful, playful, absurd, confessional, and full of love. The film in the final room of the exhibition, “Nurses Come and Go, But None for Me” (2024) combines a performative reading of Philip Atkins’ (Ed’s father) diary, written during the six months leading up to his death, with the reenactment of “The Ambulance Game”, a role-playing game played by Atkins and his daughter. Originally private, both the diary and the game are now performed publicly, with the camera alternating between the performers and the audience, emphasising voyeurism and shared intimacy.

“Nurses Come and Go, But None for Me” is two hours long. Daily screening times are 10:30, 12:40 and 14:50.

Photo: Ed Atkins, Nurses Come and Go, But None For Me (Still), 2024. Video and sound. © and Steven Zultanski. Commissioned and produced by Hartwig Art Foundation

Info: Curators: Polly Staple and Nathan Ladd, Assistant Curator: Hannah Marsh, Tate, Tate Britain, Millbank, London, United Kingdom, Duration: 2/4-25/8/2025, Days & Hours: Daily 10:00-18:00, www.tate.org.uk/

Right: Ed Atkins, Good Baby, 2017 © Ed Atkins. Courtesy of the Artist, Cabinet Gallery, London, dépendance, Brussels, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, and Gladstone Gallery