ARCHITECTURE: Hans Hollein-Works from the 1960’s

Described by Richard Meier as an architect whose “groundbreaking ideas” have “had a major impact on the thinking of designers and architects,” Austrian artist, architect, designer, theoretician and Pritzker Prize laureate Hans Hollein worked in all aspects of design, from architecture to furniture, jewelry, glasses, lamps—even door handles. Known in particular for his museum designs, from the Abteiberg Museum in Mönchengladbach to the Museum of Modern Art in Frankfurt to Vienna’s Modernism.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery Archive

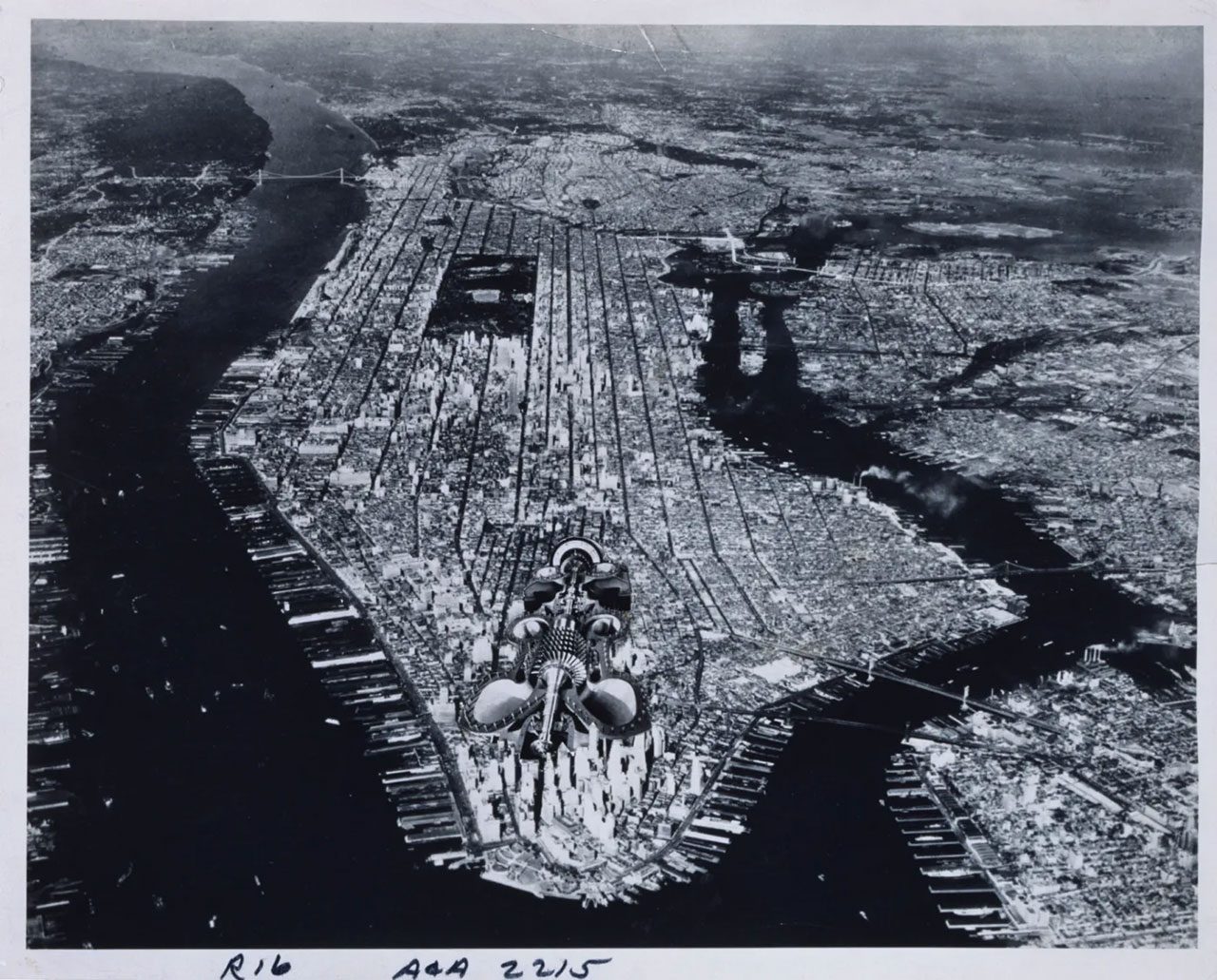

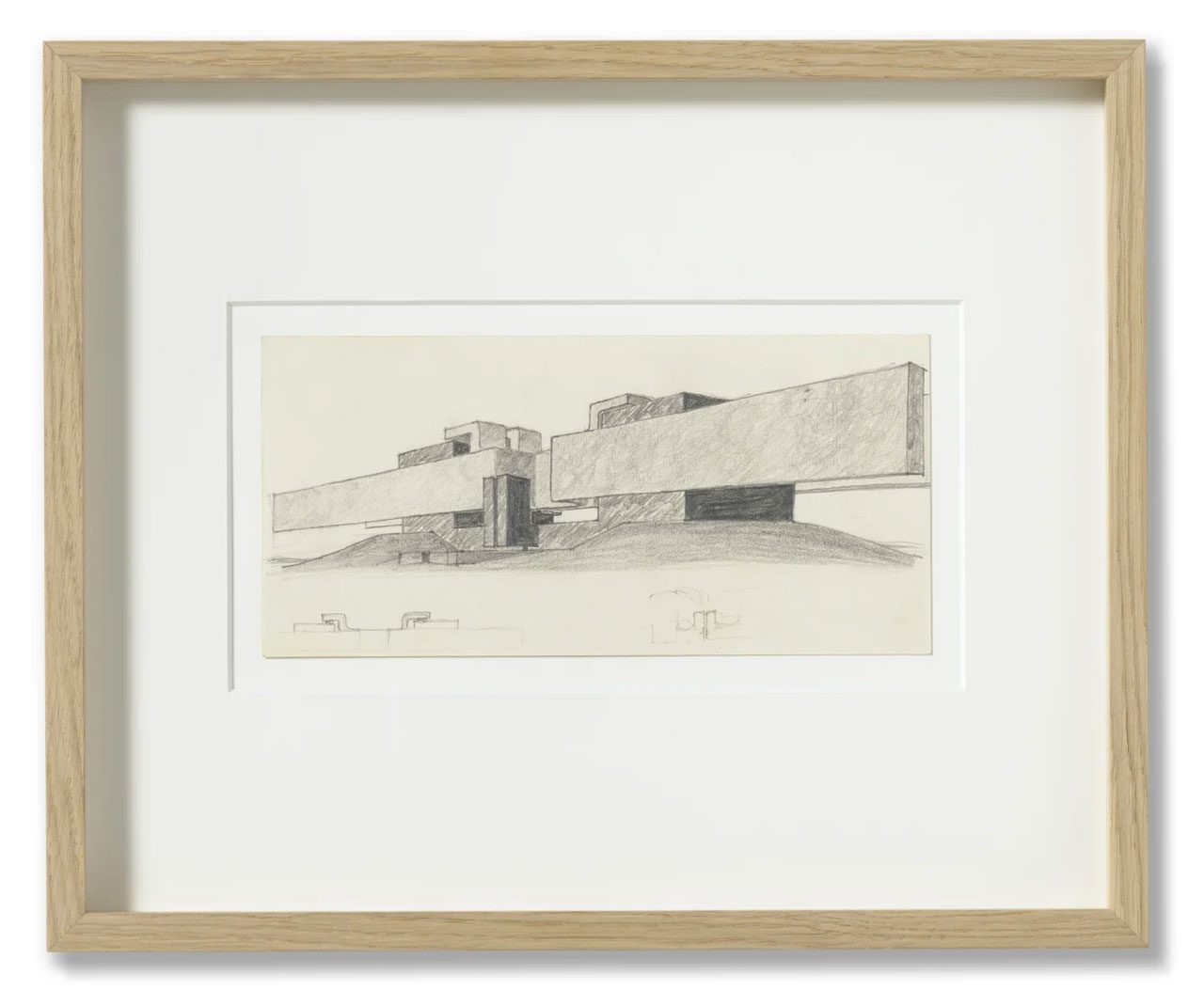

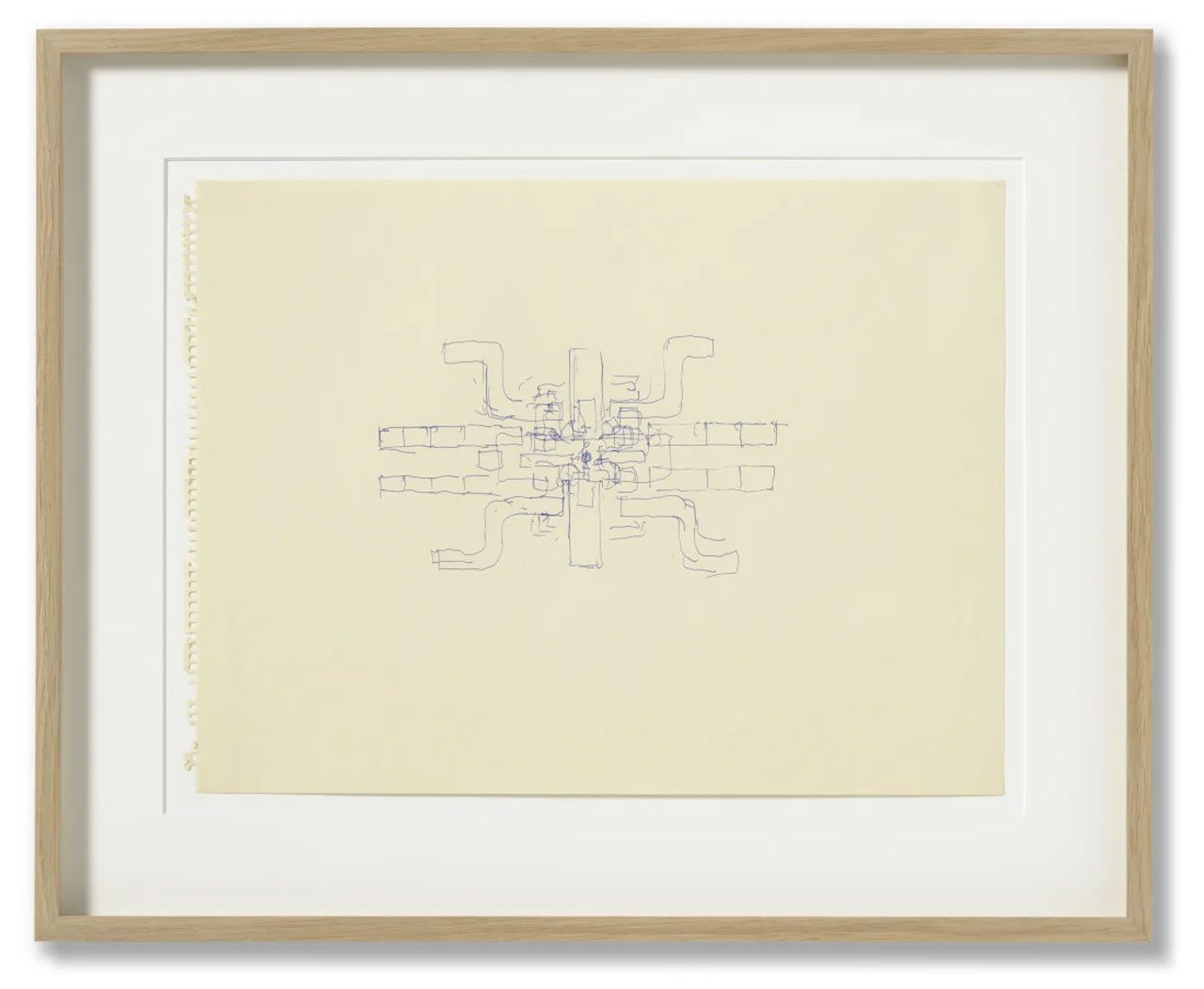

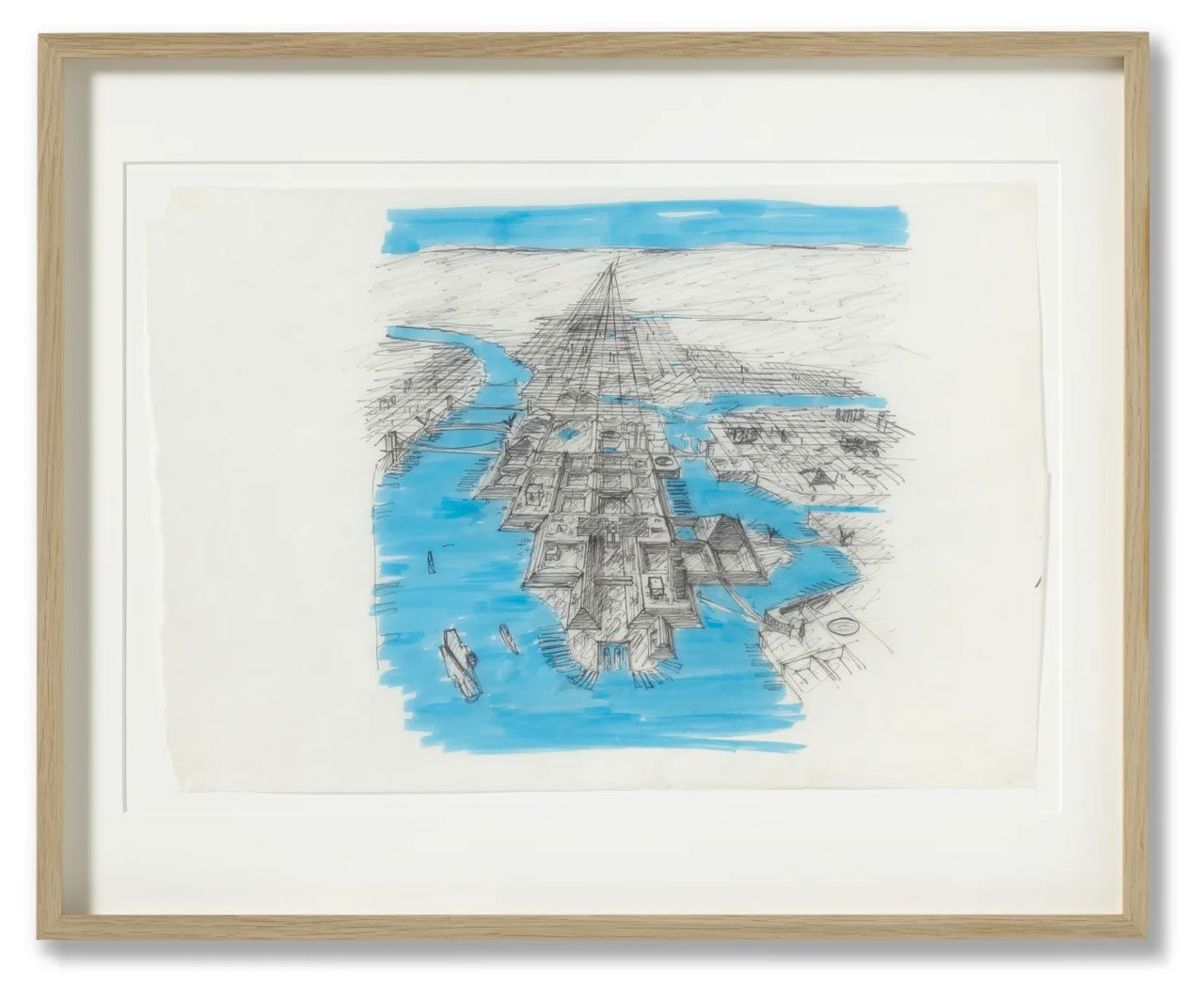

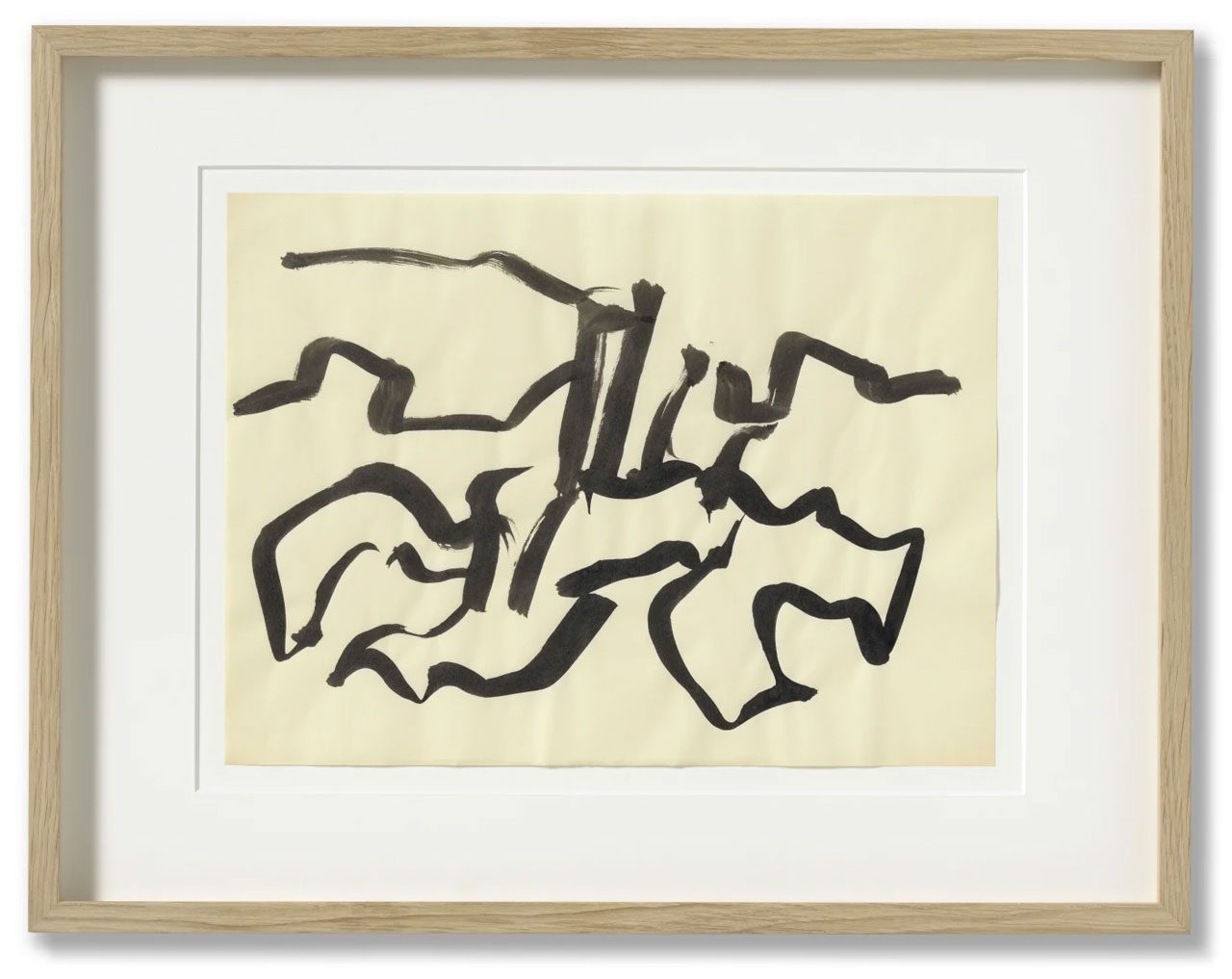

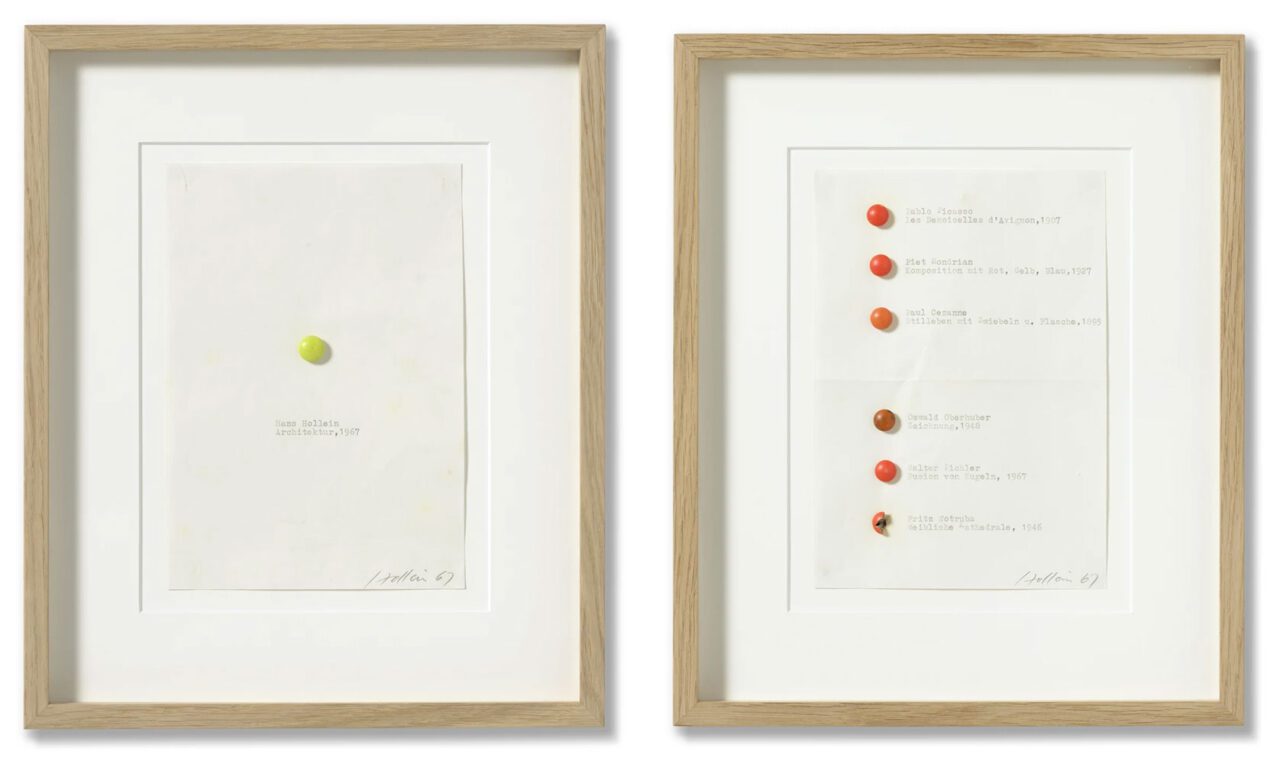

The exhibition “Works from the 1960’s” offers an insight into Hans Hollein’s practice. and presents a selection of visionary architectural drawings, conceptual works and a sculptural model that reimagine spaces, structures, cities, as well as their communicative and perceptual possibilities. The 1960s were a pivotal decade in Hans Hollein’s budding career. Studying architecture between Austria and the United States throughout the 1950s, Hollein returned to Vienna in the early 1960s, whereupon he became a key figure of the avant-garde. Hollein notably collaborated with artist Walter Pichler on a group of revolutionary architectural designs presented at the trailblazing Galerie nächst St. Stephan in Vienna in 1963. Opposing modernist functionalism, Hollein proclaimed the purposelessness of architecture, advocating for a ‘pure, absolute architecture’ in his accompanying manifesto. This exhibition proved critical, resulting in the acquisition of Hollein’s drawings and models by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. As Prof Eva Branscome writes, Hollein’s ‘‘artistic’ output was already highly collectible before he was known as an architect’ and, by the end of the decade, his works had integrated major public and private collections. At the heart of this exhibition lies “Hanging urban structure with traffic junction” (1962-1963), a sculptural model that was first exhibited in Hollein’s historic show at Galerie nächst St. Stephan. A futuristic metal city rendered in a vocabulary of intersecting rectilinear forms seems to hover above a concrete plinth, its cantilevered wings jutting out overpoweringly. The work crystallizes Hollein’s conception of cities as ‘manifestations of architectural will. Hollein sketched various versions of urban constructions that he called “Communication Interchange”. His drawings of imbricated structures resemble blown-up assemblages of machine components that verge on the totemic. An avid technophile, Hollein was fascinated by the ever-increasing scale and complexity of machines, which he sought to transform into architecture. Hollein’s technomorphic edifices shed light on his experimentation with form, as well as his underpinning conceptualization of architecture as a fundamental ‘medium of communication’ through which human beings expand themselves not only physically but also psychically. Hollein perceived drawing not only as an architectural tool but also as an artefact in itself. In numerous works on show, the line between art and architecture dissolves almost entirely. In one drawing, Hollein’s thick, inky brushwork oscillates between calligraphic art, abstract mark-making and an impression of the titular building. Hollein’s “Non-physical Environment – Architektur aus der Pille” (1967) works encapsulate the pioneeringly conceptual nature of his practice. Asserting that ‘architects have to stop thinking in terms of building,’ he strove to dematerialize the very notion of architecture in order to enhance its perceptual possibilities. Hollein thus harnessed the power of psychoactive drugs to foster artificial spatialities through ‘different pills which create various desired environmental situations. In one work, ‘Liebe ohne Furcht’ (‘Love without fear’) is typewritten beneath a pill affixed to the paper support, while in another, a list of masterpieces including Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907) is inscribed beside a dotted line of red pills, suggesting that the drugs might kindle an affective or aesthetic experience. In yet another, a white pill is simply emblazoned with the word ‘KING.’ As Prof Branscome posits, Hollein saw the drug as ‘the ultimate environment in the creation of an architecture of oblivion, dream and contentment.’ Combining a compelling minimalist aesthetic with Duchampian wit and a Pop sensibility (a tiny pill even refers to ‘Wiener schnitzel with potatoes and mixed salad’), Hollein’s prescient conceptual artworks redefined architecture as fundamentally experiential. This exhibition provides an intimate look into Hans Hollein’s pivotal early works, which highlight the multifaceted nature of his practice. ‘He is the only architect whose works are kept in the art collections of both the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the only artist to have won the Pritzker,’ states Prof Liane Lefaivre. ‘He shifts nimbly from one identity to another. There is nothing arbitrary about this multiplicity.’ Across a diverse body of works, the exhibition reveals the extraordinary breadth of Hollein’s artistic practice, as well as his underpinning radical architectural vision.

Photo: Hans Hollein, Hanging urban structure with traffic junction, 1962-1963, Metal and concrete, 23.5 x 74.5 x 49.5 cm (9.25 x 29.33 x 19.49 in), Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery

Info: Curator: Dorothea Apovnik, Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery, 7 Rue Debelleyme, Paris, France, Duration: 1/3-31/5/2025, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-19:00, https://ropac.net/

Right: Hans Hollein, Non-physical Environment – Architektur aus der Pille, 1967, Pablo Picassso, Les Demoiselles d‘Avignon, 1907, Piet Mondrian…, 1967, Pill on paper, typewriter font, 21 x 15 cm (8.27 x 5.91 in), Courtesy thaddaeur Ropac Gallery