PRESENTATION: Helen Frankenthaler-Painting Without Rules

Helen Frankenthaler was among the most influential artists of the mid-20th century. Introduced early in her career to major artists such as Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell, whom she later married), Frankenthaler was influenced by Abstract Expressionist painting practices, but developed her own distinct approach to the style. She invented the “soak-stain” technique, in which she poured turpentine-thinned paint onto canvas, producing luminous color washes that appeared to merge with the canvas and deny any hint of three-dimensional illusionism.

Helen Frankenthaler was among the most influential artists of the mid-20th century. Introduced early in her career to major artists such as Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell, whom she later married), Frankenthaler was influenced by Abstract Expressionist painting practices, but developed her own distinct approach to the style. She invented the “soak-stain” technique, in which she poured turpentine-thinned paint onto canvas, producing luminous color washes that appeared to merge with the canvas and deny any hint of three-dimensional illusionism.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Guggenheim Bilbao Museum Archive

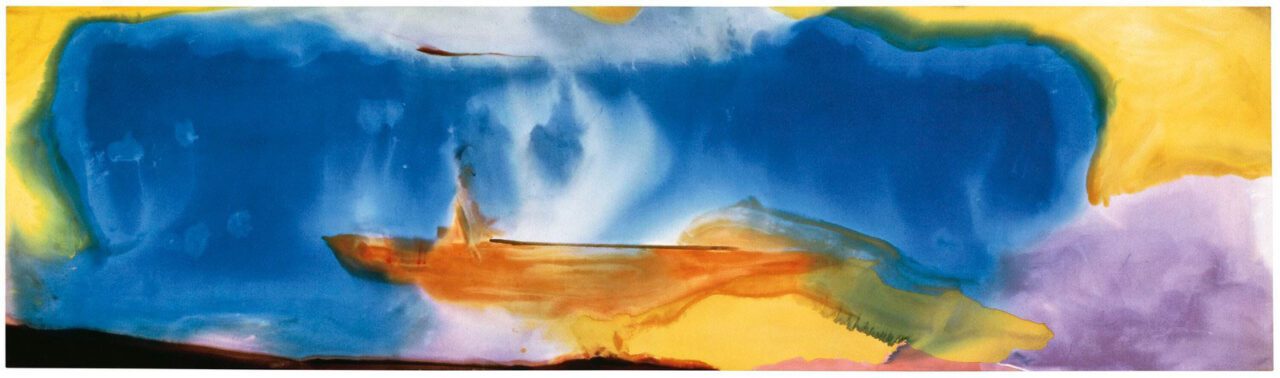

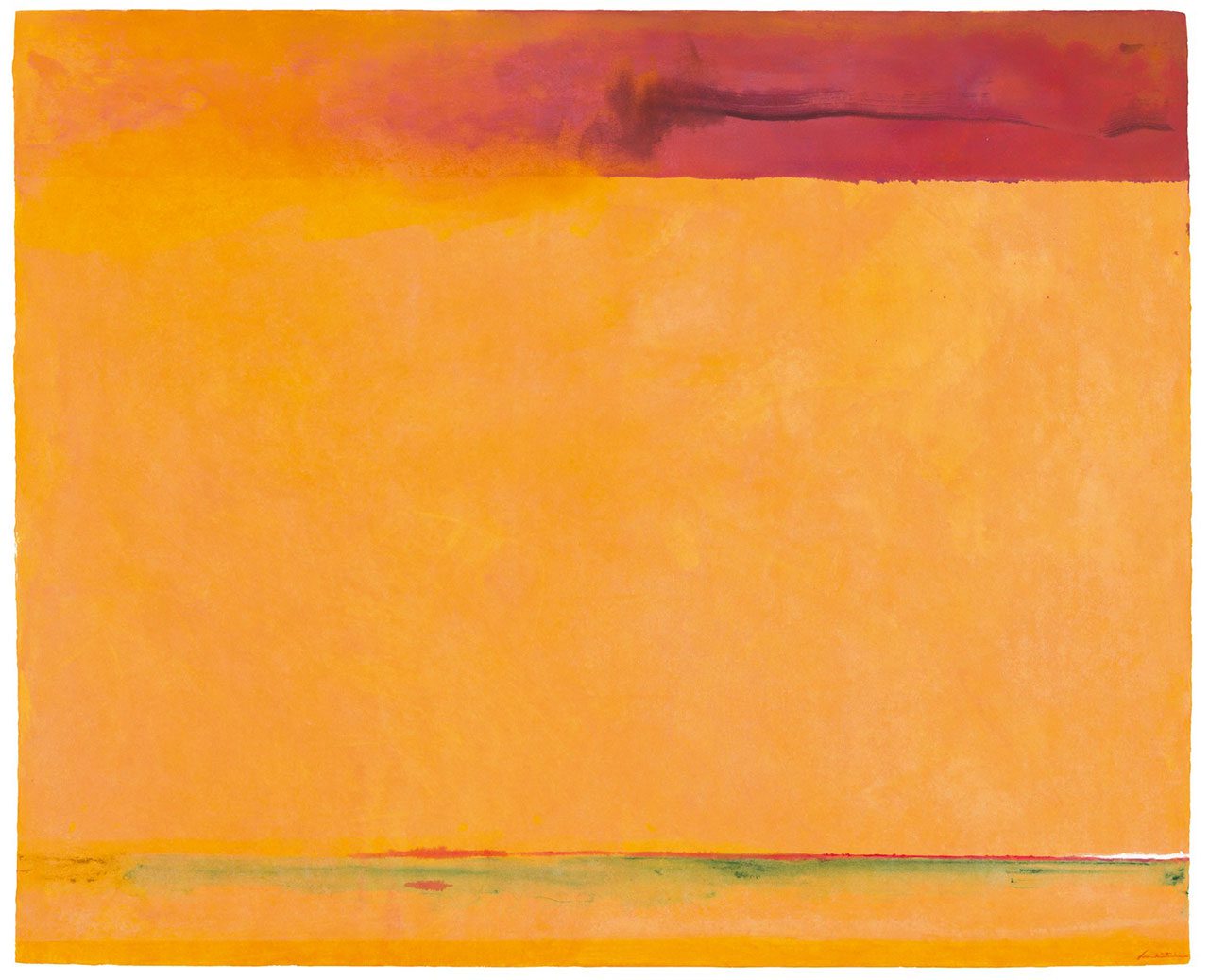

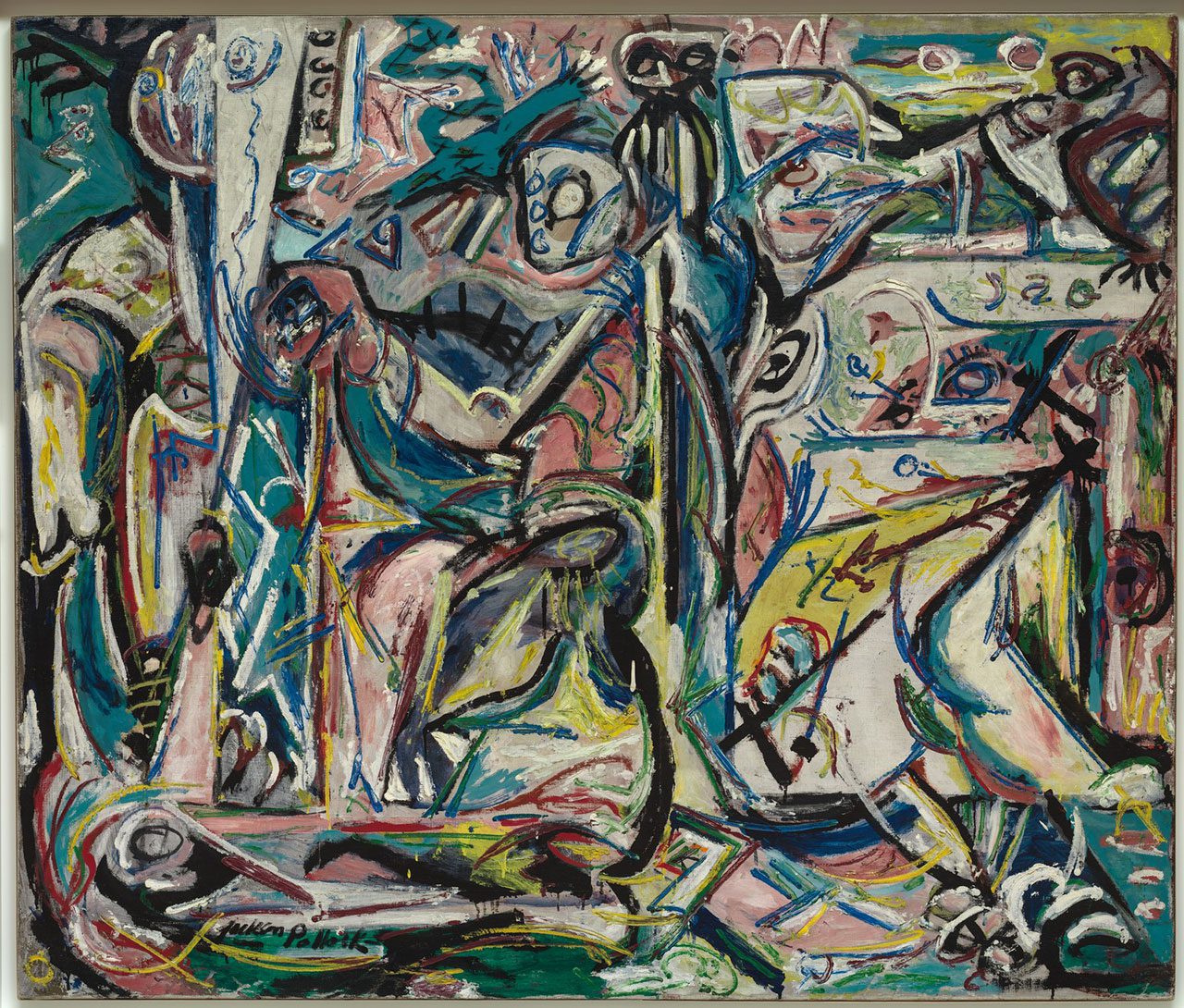

The exhibition “Painting Without Rules” charts Helen Frankenthaler’s long creative journey and achievements through pieces that span her entire career, from the 1950s to the dawn of the 21st century. In the exhibition, her works are displayed alongside those of other major artists active on the New York visual arts scene of that time. The predominance of large-scale paintings invites us to dive into Frankenthaler’s favorite theme: the act of painting itself. The exhibition contextualizes the painter’s creative output through the lens of artistic affinities, influences, and friendships. Comprising thirty of Frankenthaler’s poetic abstractions created between 1953 and 2002, the exhibition also features select paintings and sculptures by some of her contemporaries: Anthony Caro, Morris Louis, Robert Motherwell, Kenneth Noland, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and David Smith, highlighting the synergies between these artists. The exhibition will also include two additional major paintings by Frankenthaler that have recently entered Guggenheim Bilbao’s Collection. The exhibition is designed chronologically, decade to decade, beginning with the 1950s and ending in the 2000s. Each section, paced by a curatorial text, represents another chapter of Frankenthaler’s extensive career. The exhibition celebrates the legacy of a pioneering artist who never stopped exploring new ways to make abstract art. The sections are: Making Her Mark:1950s: When Frankenthaler saw Jackson Pollock’s paintings at the Betty Parsons Gallery, Pollock’s gestural abstractions had a profound impact on the young painter. Transitioning from a traditional easel, Pollock maneuvered around monumental lengths of canvas rolled out on his studio barn floor. As abstract as some of his paintings appear, tell-tale images emerge. The suggestion of subliminal imagery intrigued Frankenthaler, who responded to Pollock’s radical methods: the choreography of an improvised full-bodied gesture and the possibility that abstract painting could carry a kind of message. Abstraction primed by spontaneous drawing suited Frankenthaler’s artistic temperament as a means of projecting her imagination-as pictorial signs, symbols, and scenes-without revealing herself entirely. Ambiguity was essential. She wanted her images to remain mysterious, like poems; to mean different things to different people. Pollock enabled her to see painting as an open-ended process synonymous with drawing. The uninhibited mindset of one who draws was the catalyst for her breakout Mountains and Sea (1952), and for many of the paintings in this exhibition, including the earliest works in this section, all of which signal a precocious, prodigious talent. In “Open Wall” (1953), which Frankenthaler created in her New York studio, the title recalls the static, immobile and impenetrable nature of a wall and, at the same time, becomes open, permeated by bands of light and color. Frankenthaler said that the painting began as “an experiment to create some kind of sense of space and boundary… In the end, a spine of the painting, what makes one respond, has very little to do with the subject matter per se but rather the interplay of spaces and juxtapositions of forms. Riding the Tide, the1960s: The summers that Frankenthaler spent by the sea in Cape Cod, in Provincetown, Massachusetts (1960 -1969), with her husband, the painter Robert Motherwell, set a new course for her painting. If the weightless clouds in Tutti-Frutti (1966) pulse with buoyant abandon, the rectilinear banners in “The Human Edge” (1967) descend monolithically. Human edges can be eccentric. Frankenthaler courted imperfections just as she coaxed out humor in her work. Summers were not only a time to paint, but a chance to socialize with close friends. The sculptor David Smith was a frequent visitor. Frankenthaler and Smith shared a common belief when it came to making art: No rules! Whether you were a painter or a sculptor (or both), the mantra was the same: no rules meant never being complacent about how your art got made, the materials used, or what it might look like. Works could be somber but also lighthearted. Smith’s “Untitled (Zig VI)” (1964)-girder beams stacked, welded, and coasting on miniature wheels-teeters like an over-sized child’s toy. This section also includes “Santorini” (1965), a recent donation by the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, which marks the first of two works by this artist to enter the Museum’s collection. The painting is titled after the Greek island known for its expansive vistas of the Aegean Sea and is a prime example of Frankenthaler’s poetic abstraction. Frankenthaler visited Athens and the Greek Islands with Motherwell and his two daughters, Lise and Jeannie, during the summer of 1965. “Santorini” distills amorphic and geometric forms into a pared-down configuration suggesting elements of land, sea, and sky. Among Friends: The works in this section provide a fuller context for the exhibition. Some came to Helen Frankenthaler as gifts, tokens of friendship. Others were purchased by the artist. Two are museum loans. Frankenthaler and Robert Motherwell were married for thirteen years (1958-71). During this time, they shared family and friends, spent summers on Cape Cod and in Europe, and exchanged artistic ideas. Motherwell’s “Iberia” (1958) was painted the same year the couple traveled to Spain on their honeymoon. Mark and Mell Rothko were also part of the couple’s artistic circle. What Pollock was to Frankenthaler in the 1950s, Rothko was in the early 1960s: the catalyst for another kind of abstract image. Frankenthaler met David Smith through the American art critic Clement Greenberg. After her marriage to Motherwell, Smith became a beloved member of their family. Smith’s Portrait of the Eagle’s Keeper (1948-49), one of Frankenthaler’s earliest art acquisitions, remained with her always. New Found Freedomt, the 1970s: During the early 1970s, following her divorce from Motherwell, Frankenthaler reinvented herself. Summers became a time for travel-to Italy, France, Switzerland, Austria, Belgium, and England. She leased to a waterfront home with a studio in Stamford, Connecticut, and started spending more time outside of New York City. Eventually, she purchased a home nearby on Shippan Point and built a new studio there. From her living room, Frankenthaler had a clear view of Long Island Sound. Seascapes joined landscapes as the basis for another kind of abstract painting, tonal and atmospheric, like “Ocean Drive West #” (1974). A series of “strip” paintings from the mid-l970s evoke the vertical ascent of an urban setting. The directional white bands that bookend Plexus hum with the same erratic energy as the banners in “The Human Edge” (1967). “Mornings” (1971) is one of a flurry of images resembling geologic formations or somatic cavities. In some of the early 1970s abstractions, a chasm-like void resembles a birth canal, where blots and bleeds of color, like small organic bodies, occupy narrow passageways. The abstractions Frankenthaler conceived between 1969 and 1973 remain ambiguous, even when life circumstances appear to color their meaning. In the magisterial canvas entitled “Moveable Blue” (1973), more than six meters long, Frankenthaler pushed the limits of staining to a staggering degree-pouring, painting, and drawing with complete confidence. She trusted her instincts, always keeping her eye on the spatial dynamics of the image. This is what she had to say about the importance of space: “There is nothing flatter than a flat canvas. We honor the play and risks of fooling that surface in a way in order to create a moving spatial light. A beautiful working picture that can give flatness depth, a wonderful ambiguity. Scale, and the play of space and light are largely what it’s all about:’

Photo: Jonty Wilde

Thresholds, the 1980s: Entering middle age is a rite of passage for anyone. For an artist like Frankenthaler, crossing the midlife threshold meant confronting new realities. She knew that maintaining a presence in New York to see others’ art and to conduct business was important. She also knew that spending more time away from the city, close to the water, was not only calming but essential. It was a question of balance, and she found ways to have both, painting all the while. Frankenthaler’s respect for the history of art, nurtured early on in Paul Feeley’s studio art classes at Bennington College, never ceased. From Paleolithic caves to Monet’s late water lilies, she continually drew from art of the ages, and during the late 1970s and 1980s found renewed inspiration in paintings by Titian, Velasquez, Manet, and Rembrandt. When asked by her friend, the critic Barbara Rose, in a 1968 interview what she saw in the works of these artists, Frankenthaler replied, “the light;’ adding: “This sharpened my eye for abstract pictures. Because it’s light in the painting that makes it work:’ Scrutinizing abstract details in old master paintings (a soiled shirt or voluminous gown) enabled Frankenthaler to cross a technical threshold into a tonal world of diaphanous veils, tinted grounds, subtle washes, and transparencies. She discovered another kind of space and light and brought these to bear in works like “Eastern Light” (1982), “Cathedral” (1982), “Madrid” (1984), and “Star Gazing” (1989). Invited to Make Sculpture Anthony Caro entered Frankenthaler’s social scene in 1959, on his first trip to New York, and from then on remained one of her closest friends. The painter appreciated sculpture and sculptors, particularly Caro and David Smith, each represented in this exhibition. It is a fitting tribute to see Caro’s “Ascending the Stairs” (1979- 83) in proximity to Frankenthaler’s “Matisse Table” (1972), “Heart of London Ma”p (1972), and “Yard” (1972). Frankenthaler made all three sculptures during a productive two-week stint at Caro’s London studio in the summer of 1972. Caro provided materials and one of his former assistants. Frankenthaler approached sculpture the same way she painted: intuitively. The tiny cube that rises off the back of “Ascending the Stairs” may be a sly reference to Smith’s late “Cubi” sculptural series (1963-65)-an insider’s bond between friends. In Pursuit of Beauty, the 1990s: By the 1990s Frankenthaler approached the act of painting two ways. Both might begin spontaneously but resolve differently. One might begin and end in a single session, with only minor additions-the breakthrough she initiated decades earlier with “Mountains and Sea” (1952). The other mode-what she called the “redeemed picture”-bore a more “worked-into or scrubbed surface, often darker, more dense:· The desired result, regardless of approach, was, in her words, a “beautiful picture” that looked like it had been “born at once, regardless of how many hours, or weeks, or years it took to make it:’ “Janus” (1990) and “Yin Yang” (1990) commune like brother and sister. Sites for the confluence of opposites, both paintings share tinted grounds, layered surfaces, and transparent vectors. Some passages, rimmed with crackling trails of fire or splattered with a spew of black dots, feel like thresholds to other galaxies. “The Rake’s Progress” (1991) and “Fantasy Garden” (1992) display a dense physicality, because the painter was experimenting with gel medium mixed with acrylic and manipulated with rakes, masonry trowels, spatulas, sponges, and wooden spoons. The agitated surfaces of “Borrowed Dream” (1992) and “Maelstrom” (1992)-tough, edgy, recalcitrant-raise existential questions about the artist’s late work. This section also includes “Requiem” (1992), a recent acquisition, which marks the second of two works by the artist to enter the Museum’s collection. In “Requiem”, whose title refers to a musical composition, or solemn mass that honors the dead, stratified layers of dark color emerge from a precipitous spatial descent. Here, leaden death seems tempered by boundless light. Painting to Finish, the 2000s: The 1990s ended with major exhibitions dedicated to Helen Frankenthaler. One exhibition, “After Mountains and Sea: Frankenthaler”, opened in New York City, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1998, then toured to the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and to the Deutsche Guggenheim in Berlin. Another exhibition, at the Neuberger Museum of Art, traced her career through a selection of paintings from her personal collection. In 2001, she was awarded the National Medal of Arts, the highest honor bestowed on an artist in the name of the people of the United States. Frankenthaler always shifted seamlessly between painting on canvas and paper. Paper provided an alternative to canvas, one that was easier to manipulate and, if need be, discarded. The ongoing dialogue between paper and canvas was also age contingent. When the choreography of composing on canvas at floor level became too physically demanding, the artist easily transitioned to large sheets of paper or canvas laid out on tabletops elevated on sawhorses. As art and life commingle, the paintings on paper that followed Frankenthaler’s marriage to Stephen DuBrul in 1994 seem to celebrate a new lease on life. Optimism, buoyed by calligraphic clarity and lighthearted whimsy, characterizes “Solar Imp” (1995) and “Cassis” (1995). Frankenthaler never relinquished her dedication to beauty, even when other younger, more politically engaged artists dismissed it as obsolete or meaningless. Beauty defies simple definitions. Frankenthaler’s notion of beauty reflected the human condition. Late works, like Southern Exposure (2002), feel like veils of time fleeting. Looking at “Driving East” (2002), one might glimpse finality. But is it dawn or dusk? Even as health problems began to undermine her productivity, the artist continued to make editioned prints in the last decade of her life. Frankenthaler’s optimistic belief in beauty and persistent pursuit of an art free of rules is best summarized in her own words: “Over time, we’re left with the best:’

Photo: Helen Frankenthaler, Moveable Blue, 1973, Acrylic on canvas, 177.8 x 617.8 cm, ASOM Collection, © 2025 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VEGAP, Photo : © ASOM Collection

Info: Curator: Douglas Dreishpoon, Guggenheim Bilbao Museum, Abandoibarra Etorb. 2, Abando, Bilbao, Bizkaia, Spain, Duration: 11/4-28/9/2025, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-19:00, www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/

Right: Helen Frankenthaler, Mornings, 1971, Acrylic on canvas, 294.6 x 185.4 cm, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York, © 2025 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VEGAP, Photo: Rob McKeever, courtesy Gagosian

Right: Morris Louis, Aleph Series V, 1960, Magna on canvas, 266.7 × 208.3 cm, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York, © Morris Louis, VEGAP, Bilbao 2025, Photo: Dan Bradica, courtesy Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York

Right: Anthony Caro, Ascending the Stairs, 1979-83, Steel and sheet, varnished, 111.8 x 83.8 x 101.6 cm, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York, © Anthony Caro, VEGAP, Bilbao 2025, Photo: Thomas Barratt, courtesy Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York